I’ve been writing and submitting fiction for nearly two decades now, and while I don’t have an itemized list, I believe I’ve received about one trillion rejections. One particular criticism appeared again and again: The opening is too slow and the stakes are too low.

This complaint began to wear at me like a stone in my shoe, until it became unbearable, like a serrated plastic knife against my soul. If one more agent or editor tells me the beginning is quiet and the stakes are muddy, I thought, I’ll explode.

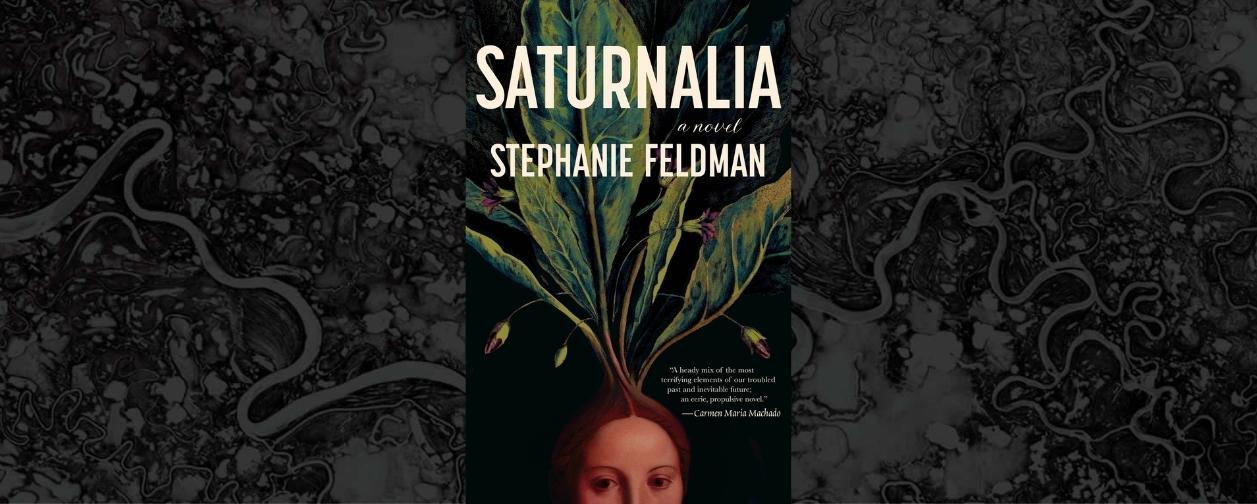

Not exploding, proving everyone wrong—these were my missions when I sat down to write the story that became Saturnalia. (Listen, passion and empathy are great, but don’t count out resentment as a motivating force.) No one, not no one, would tell me that my novel was too slow.

Saturnalia is about a lot of things: climate anxiety, social class, friendship and secrets, gender and power, the American city—as well as alchemy, secret societies, monsters, and pagan carnivals. All of the issues that matter to me, to us, and all of the trappings that make for a fun and atmospheric tale. My main character, Nina, grapples with society in decline, trauma, and the eternal puzzle of who she can trust.

But when the story begins, her problems and goals are simple. Her rent is going up, she can’t afford it, and she’s too ashamed to ask anyone for help. Into this dilemma walks Max, an old friend, who offers her a quick and well-paying job. All Nina has to do is attend the solstice party at the elite Saturn Club, where she was once a member on-the-rise, and retrieve a box carrying an unidentified treasure.

And that’s how we begin. Saturnalia is a short novel, one that aims to hold a whole world, a whole life, and to tackle all of the themes and elements I listed above. My writing will always be ambitious. It will always reach for big ideas. I won’t have it any other way. But I can’t let those ideas get in my way, either.

The goal is simple, but it’s not easy. The Saturn Club is full of painful memories, and Nina fears running into her ex-best friend, her ex-boyfriend, and her own secrets. The hook is immediate, the consequences of failure are clear; with that established, I could begin plumbing the depths of Nina’s psychology and the society she must navigate.

Writing this novel taught me how to keep the story and reader from getting lost before we even have a chance to begin. The “inciting incident” sets the story in motion. Keep that incident—and the problem and choice it yields—straightforward and direct. Make it easy for the reader to engage. Then throw every challenge you have at them; they’ll be prepared to meet them.