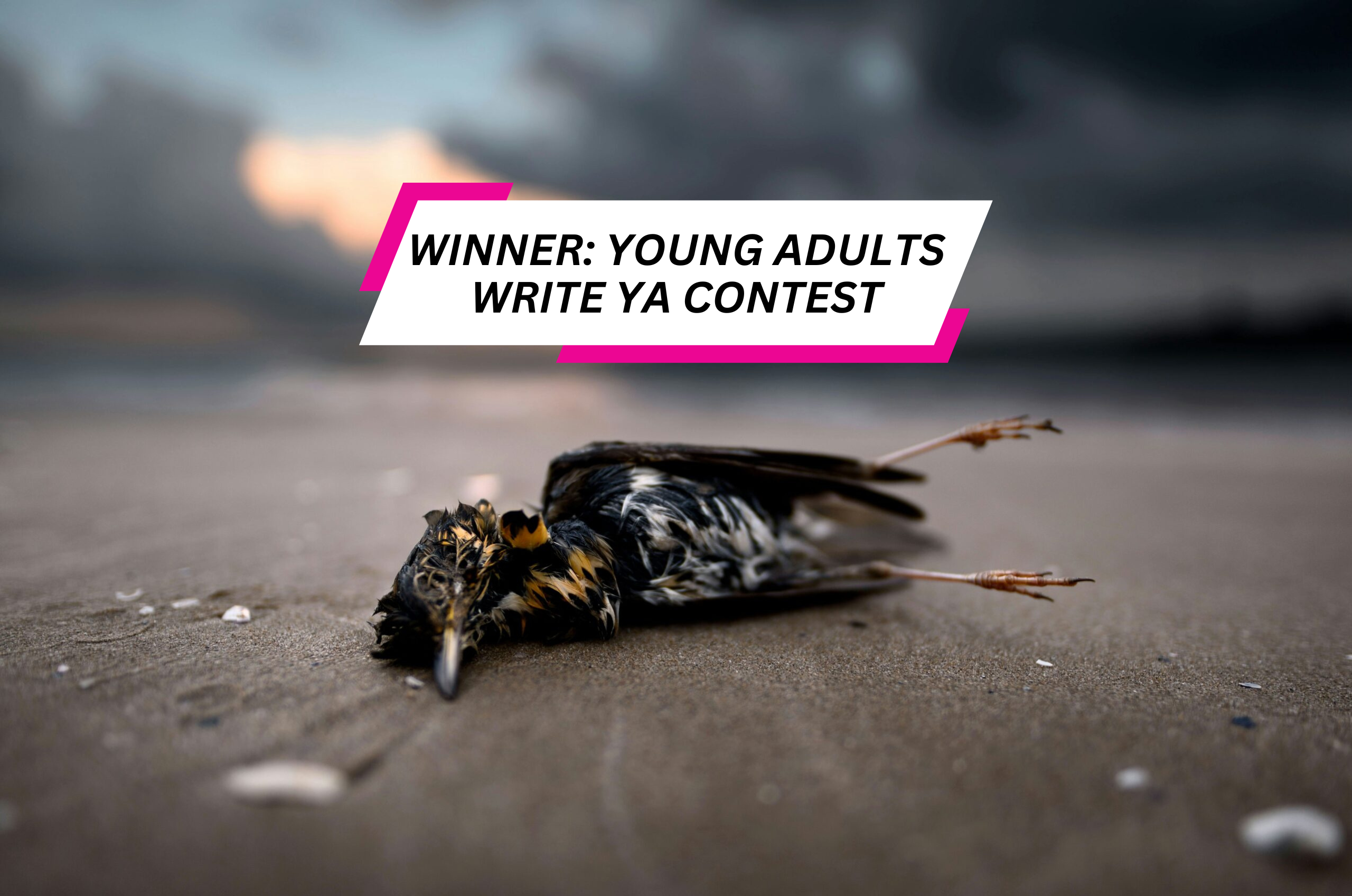

“The Bird Bag” by Karen Elizabeth is the third place winner of the Young Adults Write YA Contest hosted by Voyage YA by Uncharted and guest judged by Theodora Goss.

XXX

“The Bird Bag” is a wildly ambitious story in which Karen Elizabeth creates an entire fantastical world, with its customs and beliefs. We are shown that world through the perspective of the protagonist, Pel—but because Pel inhabits that world, we see only what she sees, so we have to intuit the parts of the world she does not explain to us. What we do see suggests a much larger reality, one that is strange and magical, but also gritty and real. Karen does a wonderful job of putting us in Pel’s point of view—we feel what she feels, both physically and emotionally. We also feel for her, and it’s a testament to Karen’s skill that while I did not always understand what was going on in Pel’s world, I always understood why it was important and how much was at stake. The imagery and poetry of this story were captivating. —Theodora Goss

XXX

Pel snaps the bird’s neck.

Defective, she thinks. The creature goes limp in her hands: a barn swallow, orange throat now warbled, felled by her hands the very minute it failed to fly.

Today marks the start of the Harvest. So Pel places the swallow in a bag, paper brown and already sagging with the weight of the mutilated wren and sparrow. Defective, defective, defective. She places her dirt-stained hands on her bare knees and rises out of her squat. Pel’s skirt falls back into place, covering the grime that lingers on her skin. Now her hem shifts, swaying with each step she takes away from the side of her house. The bird bag stays clutched against her chest. Wren, sparrow, swallow. Pel purses her lips and clenches the bag tighter. She knows she shouldn’t enjoy being given such difficult birds to Harvest. But she likes the feel of their precious, fluttering breaths against her palms; likes the tiny, beady eyes that twitch this way and that.

These birds did not twitch—not until she placed her fingers against their too-small necks and throats and pushed.

Pel’s house is nearly as old as the Harvest itself. She’s been here all her life, tending to the birds like the mother before her and the mother beyond that. All of them, mothers of the birds. Keepers of their lives: cullers of the weak, pruners of the unworthy. Pel’s hands are dirty. She approaches the front doors and does not acknowledge them as she shuffles past. Instead she opts for the side entrance, a single oak door without inscription. The handle is polished by fingerprints, gleaming brightly in the first light of day. She peels a hand away from the bird bag to open the door. The metal is cool and unyielding under her fingertips. How unlike the birds, she thinks, and remembers the erratic pulsing of those defective hearts.

Dust pushes past Pel and spills out into the open while she surges into the darkness. One hand stays against her chest to hold the bird bag aloft while the other traces the length of the hallway. The mother before her preferred the front door. She was also fond of light: a candle every four steps, unlit, tells Pel how far into the hall she already is.

Twenty candles further and the hallway falls away from her fingertips. Pel knows the new room only by her constant occupancy of its space. She takes calm, umbrous steps to the windows and parts the curtains. The natural light feels breathable in comparison to that of the candles.

As sunlight creeps in through the windows and settles tentatively against the cracked veneer of her worldly possessions, Pel sets the bird bag down next to another. It is heavier, musky like soggy produce and rotted leaves. Pel reaches her filthy hands into the second bag and takes heaping handfuls of its contents, searching for the ones that feel spherical on one half and triangular on the other. Into her apron they fall, clacking against their brethren in a disinterested clatter.

Pel takes the rest of the contents of the old bag, the ones that do not matter, and carries them to the sink. Frigid water bursts from the tap and she drowns the bag whole, washing away the unbecoming stench and banishing their mortal impurities. As she dries the rest individually, she sorts: every other is thrown away, trashed forever. The ones she does not discard are bundled and prepared to take to market.

She takes the new bird bag—wren, sparrow, swallow—and puts it where the old bag was. Pel arranges its paper face with tender, maternal attention. The bird bag gets the best view of the sloping mountains beyond the windowpanes. Defective, she reminds herself, and almost as an afterthought, shifts the bag slightly to the right. It covers the exact rectangle that the previous one made as the bottom paper leaked out its rot onto her old table.

Pel kicks aside her sleeping mat before she can trip on it and marches to the cabinet. There she finds all the supplies most coveted by the mother before her: lovely gloves made of gossamer and lace; darling hats woven by the market’s best artisans; gardening tools polished until they gleam. Pel ignores the gloves and hats in favor of the only tool she’s ever bothered to borrow: a shoddy metal trowel, rusted around the edges and splintered at the hilt. Her favorite.

Tool and treasures secured, Pel takes to the side hall and returns to the side of the house. The sun is now awake in full, greeting the world for all it’s worth. Pel does not say hello. Instead, she devotes herself fully to her task, kneeling before the patch of dirt and paying no heed to the skirt that slips a half-inch higher. Pel grasps the trowel and goads it into the plot of land. The motion repeats itself. A hole forms around her ministrations and when it is large enough for each of her fists to fit in, one atop the other, Pel allows herself to take a break. She sits back on her haunches and observes the rest of the garden.

Ninety-three pairs of stalks stuck out of the ground last night. She’d been proud of each of them, had nearly smiled to see how many had managed to sprout for her. Seven had failed to sprout—and another three were unHarvestable, but it was such a small number compared to how many failures the mothers who lived here before her would make. With each generation the window of leniency grew smaller, the acceptable number of failures lower. If Pel’s next batch did not reap the same success…

Pel reaches into her apron and pulls out a seed. She brushes a thumb over its sleek, ivory shape before nestling it deep within the hole. She spits on it, saliva glistening on both earth and bone. Then both hands reach to sculpt the dirt over the cavity once more.

Again she stabs into the ground. Again she fishes around the inside of her apron. Again she drops a single skull inside, spits, and covers the hole. Again for ninety-eight other holes.

Pel is lighter when she finishes. Her hands do not feel so dirty. So this time she goes through the side entrance with both hands trailing the surrounding walls, glossing over the firmaments of her enclosure like she imagines the seeds exploring their plots of dirt.

Disrobing, she selects new clothes: a longer skirt—brown. Dirt. A humming yellow headscarf. Sunshine. Black boots with panting laces and taunt tongues. The place where failed mothers go to follow defective crops. A blue blouse, silken and untethered just like the sky. And a green scarf. Not for any particular reason. Pel simply likes the color, because the mother before her did not. Pel does not look at the bird bag as she drifts to the sink where her bundle of merchandise rests. A second after she spots the bundle, she tucks it into her new skirt’s pocket and flees from her house.

The market square is a third of a day’s walk from her house. Pel takes confident steps, free as a bird as she strides down the mountain path to the valley below. The sun is peaking by the time she touches down in the market. She has a permanent stall available to her at the edge, reminiscent of the lingering respect for the mothers of the Harvest.

“Good day to you, Mother Pel,” a stallkeep greets as she passes. Pel does not return the vocalization. No mother ever does. She is but a tool for the humans, a bridge between the crops and the benefits they reap. Sacred but for her objective value and her margin of profit. If Pel does not continue to meet the demands of those who value her services…

Pel studies her tar-pit boots. They are the first of the four objects given to new mothers: the bird-black boots; then the key to the house; then two bird bags, empty save for one, carrying the fourth gift.

A hundred bird skulls.

The mother’s stall is shorter than the rest, with a small lip onto which her wares can be placed. It is made of light birch wood and thatch, with a shabby stool placed on the other side of its front panel. Simple and without decoration so as to discourage theft and vandalism. Vacant save for the days in which she migrates down from the mountain. Pel steps around to the stool and sits. Various greetings gloss over her head—without her returning a single one—as Pel unties the bundle and allows herself to sink into her work. Untied, the contents of her bundle now sprawl over the length of that small wooden lip. Pel sorts ulnas from tibias from coracoids from pygostyles. Every bone has a place has a name has a bird it was once attached to before it became—

“Defective,” a commoner snarls. The poorest among the village do not care for Pel’s involvement in their lives. Defective, to them, is a word both for the birds and for their mothers. Only those with silver bits, with stomachs lined in velvet, can afford the delicacies she brews up in the mountains. Only those with coin to spare can praise her—leaving the destitute with only the luxury to scorn her.

“Do not sully Mother Pel’s stall with your rubbish.” The speaker is someone Pel knows intimately. A friend, perhaps, in another life. She is unbecoming in every implication of the word: long, ashen hair. Tawdry, listless eyes. Skin prickled with mottled brown spots like the plumage of a barn owl’s belly—but with a smile warm enough to melt the snowy peaks far above their heads. Between the two of them, only the once-friend retains the expression. “I’ve come to watch today’s Forecast,” she explains once the peasant has taken himself and his trail of filth farther into the market. Pel’s last tie to a life she does not remember always speaks with such a soft, considerate disposition whenever she addresses Pel. She’s yet to hear her speak that way to anyone else.

The sternum she rocks into place stills beneath her fingers. Yes, the Forecast. Only for this does Pel emerge from the house on high. To the villagers like the one before her, this is the one way they are able to assess the usefulness of the mothers. Pel must perform admirably today, or—she grinds the toe caps of her boots together. The movement helps her think clearly. She would ask for the name of the girl before her if she knew how. But there is no time, no way for her to find a way around the void in her mouth before the rest of the crowd arrives. Pel does not clear her throat. There is no need to practice the mannerisms of the speaking when she cannot speak herself.

So Pel moves the bones. She shows the crowd the numbers, made by the bones she arranges: ninety-three sprouts, she tells them. Three defective. She is proud of these numbers. They are the best numbers any mother has been able to achieve. She is the best of the mothers, better than the mother before her and the one beyond that. She twists the too-short fleshy stump in her mouth and imagines probing the masses before her like a woodpecker investigating insect-ridden bark with its tongue. She wonders if they, too, approve of her numbers. The faces before her give her no answer. Pel forgot how to communicate with humans long ago.

Her hands stumble over a vertebrae shard she failed to remove earlier. It alarms her, that oversight. She looks down with widening eyes at the piece and, though she knows she ought to sweep it discreetly to the ground, lets it linger on the slab of wood while she manipulates the bones around it. She does not like the vertebrae, and she does not like them because the villagers do not care for them. They do not want to see proof of how the defectives are weeded out. They do not want to see which bones must bend in order to bring them their Forecasts.

A new number forms under Pel’s supervision: ninety. Inside of the e, nestled safely in that pocket of enclosed space, she has left the vertebrae shard. She does not recall which of the birds from the last Harvest it belongs to: birds are bones are dust. They are all the same when they are defective. But Pel has made a vow with this number. She has promised both the villagers and the birds that she will reap exactly ninety crops during the next Harvest. It is the number she has always promised. The number she has always given.

And perhaps it is because Pel’s hands are still dirty—how did she forget to wash them before she left?—or perhaps it is because her bundle is dirty—why did she let the vertebrae linger?—the nearest villager frowns. He is a rich one, she can tell, because he carries himself like a proud osprey. Next to him flits the barn owl woman. Her eyes flap closed dully. They are not sad. When she smiles, it is greedy. Her smile is paralleled by the smiles of the osprey, of the other humans in the market.

A hand reaches forward and adjusts the bones for her.

Her new number is not ninety—it is ninety-three.

Then the villagers fly away.

Pel does not fail to notice that the vertebrae shard is gone, too.

She bundles up the bones again and drifts through the market to sell them. They are purchased almost as soon as she holds them out, because if there is one thing these villagers love, it’s the touch of the bird mothers. She cannot voice the price she wants; can only accept the coin offered. Her neck is sore from bowing her head so often. “Good day to you, Mother Pel,” the stallkeep says as her bones are pocketed. They’ll be sold to the fortune tellers that sweep through exactly twelve days after she visits. And in return, the fortune tellers will give them bushels of lala herbs and ephedra, or even a pouch of pepper if the bones are especially good. Pel knows the ones she just forked over are worth at least three pouches and a half of pepper. Enough for the stallkeep to close shop for the next four seasons.

But Pel does not protest; does not fight or argue. Instead she takes the coin and moves on to the next stall, using the copper bits to pick up new supplies: a tin of lard; a pinch of salt. The market frequenters know what the mothers buy. If there is any extra coin left over for her—and there is not—she would spend it on a butt of bread, freshly baked. The last of her coin goes to the stall at the exact opposite end from her own. It is everything that her stall is not: tall, dark, lavish and lustrous. Inside is the woman who watched her Forecast. She watches so that she will know how many skulls to prepare for Pel’s eventual arrival.

“Only three defective this time,” she says by way of hello. Her smile is bright, because the fewer crops that fail to Harvest properly, the more business she receives. She does her math aloud while Pel waits, scraps of salt and tin in her pocket. “Let’s see, then. You’ll need ninety-seven new seeds this time. That’ll cost…” she trails off. She knows the number she wants to give. Pel puts out every coin she still has, but still the woman spots the bulge in her pocket and smiles. “I’m afraid that we’ve had to raise our prices a tad since we last saw you,” she offers apologetically. “It’ll be six copper bits this time.” Pel has four remaining: two went to the tin, and one to the salt. So she sets the coins down and fishes the lard out as well. “Thank you, Mother Pel. We’ll see you in a fortnight.”

Pel takes the new bag, almost full to the brim, and leaves with the morsel of salt she managed to keep for herself. On her trek back up to her house Pel wets a single digit on the inside of her cheek and sticks it into the tiny pouch before popping the pad of her index finger back into her mouth. She likes the taste of salt. It’s hard to savor without a muscle to rub it around, so instead she lets the gritty sensation linger for as long as possible before it disintegrates.

And so, a day passes. Dawn bleeds into dusk as Pel takes her new bag and empties its contents into the other bird bag—wren, sparrow, swallow—and lets the new seeds weigh down on the old Harvest’s defectives. A day, and then another. Pel pops tiny fingerfuls of salt into her mouth as she watches the garden, opening the curtains at sunbreak and closing them at twilight. She paws at the dirt outside and sweeps the side entrance hall. The scent of rot suffocates her and she lets it. Her hands are dirty. The old bag sags as the bottom browns, leaking. Pel does not clean it, but she does not let it run farther down the table than it has already gone. She thinks about the feel of those feathered chests often as the first signs of the next crop begin to show, minuscule three-toed stalks breaching the dirt’s surface. Pel counts the numbers eagerly, nodding to herself at their progress. The Harvest will be better this time—ninety-six pairs of lanky legs have now appeared in the ground. She is on track to meet the new demand of ninety-three. Pel marks the turn of the moon and knows that the fortune tellers will be passing through tomorrow, purchasing the bones of the birds said to have special properties thanks to the mothers’ careful farming. What a curiosity it is: those who cannot eat what she grows, savor the scraps. Those who cannot obtain scraps at all scorn her.

The Harvest returns before Pel is ready. She dresses in the too-short skirt, with the apron lashed above it. She cleans and washes her hands carefully. Then she takes the empty bag, the one she received the seeds in, from where it sits next to the heavily rotted bird bag and drifts outside. The garden waits for her as it always does. She wakes well before dawn only on the days of the Harvest, so that she may uproot each and every one of her hundred crops before the sun can witness what it is that the mothers do.

Pel kneels in the dirt and sets the bag next to her. The skirt slides up a half-inch. Careful not to touch the dirt with her clean hands, Pel moves first for the patches where no stalks can be seen. She inhales. Then thrusts both of her hands at once into the soil, collecting grit underneath her fingernails, as she probes the dirt for the seeds that did not root. She finds the four failed seeds easily, all in different states of growing. One has attempted to grow sideways. The second only managed to grow half of its bones. The third made it all the way to the muscles, and even the feathers of the head, but did not manage to unfurl its curled legs in time to finish the rest of its growth. The last did not sprout at all. Pel takes them all and carries them back to the trash by the sink where she throws away the bones that do not make it into the Forecast bundles. Her hands are washed again. The ones that do not sprout are not her fault. She can be clean.

She returns and greets the garden like an old friend, a tentative ally. She hopes now only for the best. She reminds herself that she is here because she is the best mother, because she is better than the mother before her and the mother beyond that. Pel wraps a gentle hand around the first of the ninety-six pairs of stalks and slowly, carefully, uproots the bird.

It is a parrot. Pel likes these, because their colors are always as vibrant—if not more so—than the clothes she wears on Forecast days. She brushes the dirt off the bird carefully, tenderly, inspecting every inch available to her eyes before deeming it safe. Structurally sound. She breathes onto the bird, gently, and it stirs to life there in her cupped hands. The parrot twitches—a true success—and she is happy when it unfurls its wings and squawks at her curiously. Pel almost smiles as she points to the valley below, where all her birds fly, where the villagers wait with empty nets and polished plates. And up into the sky the parrot goes, obedient always, heading down to those open mouths, solidifying her existence here, in the mountain house each set of wings pays for. She moves on to the next plot. Her hands have dirt on them, but they are not dirty.

The first defective bird is a budgerigar. It is blue and green and perfect in every way, yet when Pel breathes life into it, the bird does not twitch. She does not breathe again because it is forbidden in the extreme—so much time to Harvest, and not an extra second can she spare—so instead she shifts her hands and adjusts her grip. Fingers poised just so, Pel applies pressure. The vertebrae in the bird’s neck snap like twigs. She places it in the empty bird bag and brushes her hands off on her skirt. The grime does not wipe off.

The next defective bird is a sun conure.

The next is a plover.

Then a sandpiper, then a hummingbird, then a finch.

Pel is shaking. There is one more left, and already she is at her limit. She has failed to provide the new amount demanded of her, but at least she can still provide her usual number. If this one flies. There can be no more defective birds. The bird bag next to her is so full, already at double what she placed in it last time. Pel cannot fight the tremor in her hands as she carves out an entire pit around the last pair of legs poking out of the dirt. She knows she is stalling, and yet she cannot refrain from combing every kernel of earth away from her last bird for this Harvest one at a time. She extricates it with the natural force of her fingers so greatly restrained that it is almost as if the bird lifts itself out of the dirt. She brushes the soil away from between each of its winged feathers with a single pinky finger. Pets the grime away from its feathered brow and transfers it onto her hands instead.

It is a barn swallow.

The throat is a cheery orange, ripe like a tangerine. Its crested head is the deep blue of the ocean Pel can smell whenever the winds drift in from the east. Its belly is white like fledgling snowfall. Cupped in her hands the bird is safe. Nestled in the soil of her garden it was free to grow, free to return to life under the permission of the mother greater than the one before her and the one beyond that.

It is so small.

Pel breathes.

The barn swallow does not twitch.

And Pel tastes salt in her mouth, trickled down from her cheek. The sensation reminds her of every individual grain of salt she savored while she watched over this delicate creature for the last fourteen days, protecting it from the denizens of the forest that prowled the outskirts of her fence when the moon was perched high in the sky. Pel recalls every day that passed with salt staining the inside of her cheek since she held the last defective swallow. She sucks air in. Defective, she thinks.

But—Pel’s heart lurches in sudden birdsong—why? Why is it, she wonders suddenly, that the birds must live again in order to die? Are they eaten exactly as she Harvests them: crested heads twitching, wings sputtering, spindly talons jerking tufts of feathers out of their plumage as they spasm in their death throes, in the embrace of a hot mouth and tepid teeth? Pel parts her lips and imagines for a single, glorious second, that she is the kind of person who can feast instead of farm. That she can do the culling, rather than be culled herself.

Would she feel any less filthy? Any less despicable?

Defective, she reminds herself.

You’re both defective.

Pel breathes on the bird again anyway.

The precious little bird does not twitch, but still she cannot bring herself to reposition her hands. Instead she draws them closer to her center, pulling them towards her heart and bringing the swallow with it. Its thin body still radiates the warmth of the earth even though she could not get it to breathe, and somehow that makes Pel terribly upset. Salt floods into her mouth in earnest and she knows not how long she stays there, in the garden next to the new bird bag while the previous one sits rotted on the table inside the house of the mothers.

Pel’s chest aches. She can hear the villagers marching up the mountain now, can see the sun directly above her, and she knows that they have come to claim their dues. She is not the mother they need. She is not the mother they want.

But she wants something, she realizes, as she looks down at the swallow once more. Not unlike the birds, she thinks. She is not unlike them at all.

The barn owl and the osprey are at the head of the group. She knows because she is still higher and can see farther. The procession is angry, alighted with flames, poised with metal barbs. Pel stands in a rush as she spots them and flees indoors. She carries the bird directly to the front entrance, because there is no time to make for her regular point of entry. One hand keeps the swallow cupped to her breast while the other flings the rightmost door open. It thuds against the wall with a clang louder than every sound she has ever made in her life. Salt still streams into her mouth but slower now that she has purpose.

Pel rushes, and knows from the sudden urgency in the villagers’ steps that they have noticed her flight. She wonders idly if they are used to chasing down defective mothers as she flings the doors of the cabinet open and reaches for the trowel with the splintered hilt. When she grasps it she spins on her heel and turns towards the side entrance, running past all twenty-one candles until she’s back outside under the sun. She is closer to the back of the house and so she runs, surges onward as the villagers arrive at the foot of her house and dart both inside and around its walls. Pel hears them advancing and stops, her breathing ragged.

She looks down on the bird she has failed—the last she will ever consider defective, the first she shall redeem herself through—and plunges the trowel deep between her ribs. There is no cry waiting to be released upon her lips, for she has no organ to form it by, but Pel feels the pain all the same. She twists and the world becomes a tunnel collapsing upon itself. She is dirt, she is earth, and she will return to the dark lands of the mothers and defective birds. The rusted metal grates against her ribs, licking its barbed edge against her bones, prodding its way into her twist by agonizing twist. She juts the splinted hilt up and gasps, near-vomitous at the sensation, troweling out the thumping mound of red flesh. It throbs like a festering wound, leaking red pus, spurting liquid guilt, expelling every grievance she’s ever garnered, every sin she’s ever shouldered.

Pel places the swallow in the cavity in her chest and collapses on her knees.

“She’s back here!” Strong hands become vices on her forearms, seizing upon her from behind. Pel’s head lolls jaggedly at the brash movements. “We’ve got her.”

“Good. Take her away. Daughter Lal will take her place.”

Pel is yanked back, and her legs become a twisted nest beneath her, catching and tripping her up instead. She falls and the pressure on her arms falters with surprise. Pel does not hear what they say, but she knows that she has alarmed them, because the hands cuffed against her relent and do not immediately reconverge on her skin.

And something pulses in her chest.

Pel is warm, for a moment.

Then a cobalt-crested head peaks from the gaping wound she carved, twitching, and springs into the sky, taking all the warmth she had to give the world with it. Pel laughs as the barn swallow climbs into the sky. She watches it escape and circle above her for a brilliant, fleeting moment, sparkling coal eyes alight and focused on her. Pel’s sight wavers as she points—not to the village, but to the sky, to the mountains beyond the village and the sun itself.

The bird chirps in reply.

Pel pockets the sound and warbles back.