1964

The sideshow is a part of me.

Crimson and cream strips wind about the helices of my genes.

If I listen closely, I can still hear the calliope, its fluting notes echoing in the water traveling through the pipes in the walls.

Sometimes, the shouting of the warden takes on the authoritative bark of a carnival talker, ordering me to step right up, line up, and stand against the wall.

This cell is my tent on closing night, the theatre where I am to perform my grandest finale, a swansong fit for the carny queen I have become.

I am only waiting in the wings, I tell myself.

Waiting for my cue.

My fanfare.

My ballyhoo.

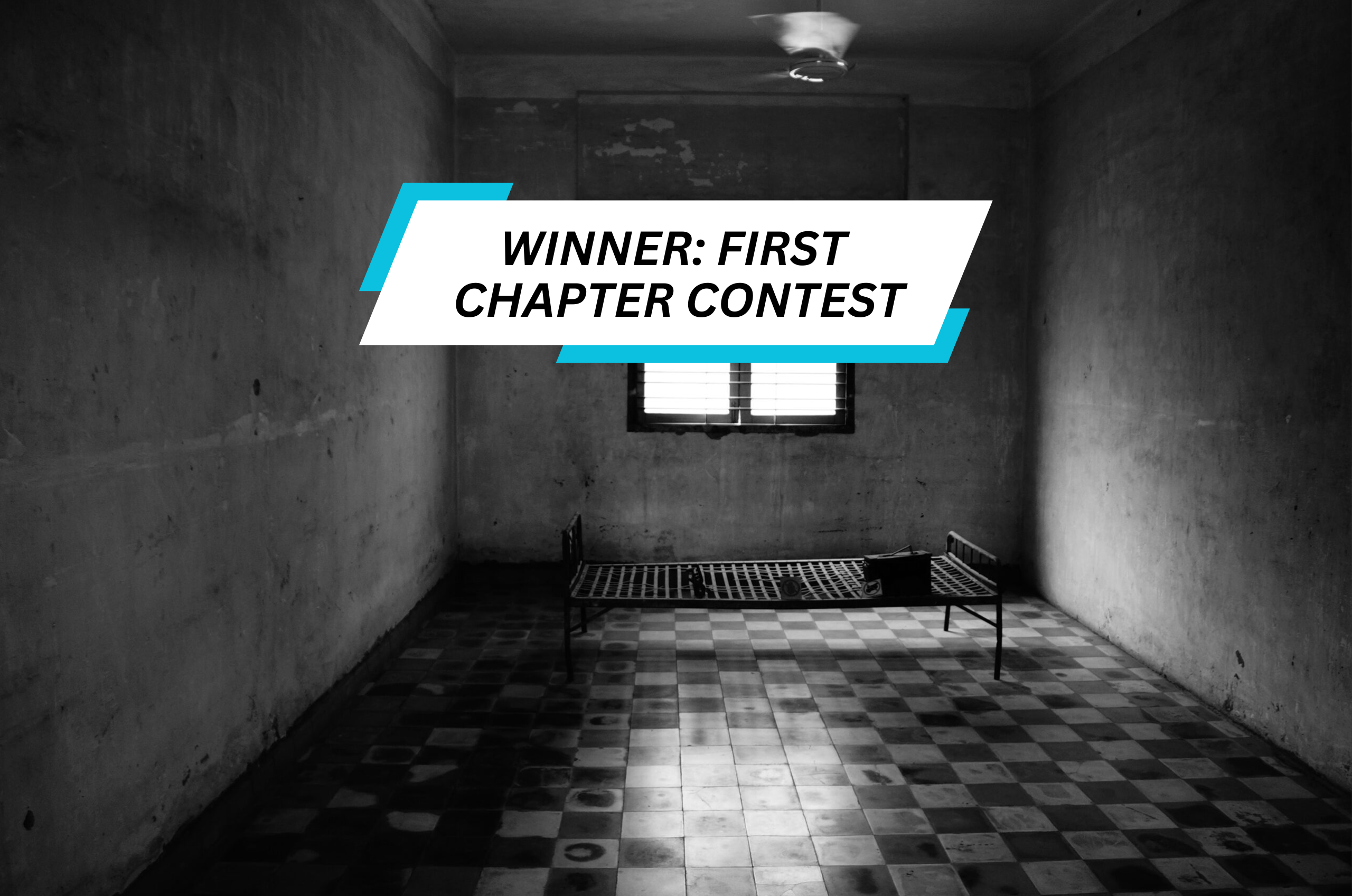

There is no light in solitary confinement, deep in the lowest cellar of the asylum’s maximum-security ward, so allow me to set the stage for you: in the corner, a bucket sits, imitating a commode but more closely resembling an experiment in the growth of fungi cultures. Against a wall, a narrow wooden pallet in lieu of a bed – but no blanket, no sheet, not even one of those made so tough that they can never be shredded and fashioned into escape routes, like a ladder of knotted rags or a noose.

Of course, a ladder would be no help down here, where the only windows are the circular portholes centered in the ironclad doors that doctors use to observe me in my unnatural habitat, like the men behind the two-way mirrors of the peepshow I once worked; I have grown accustomed to being watched by men whose names I will never know.

And then, there is me, clenched in the fetal position upon the flagstones, heralded by no drumroll or spiel, no slow camera pan or gradual brightening of the lights – the very same mystery woman you have read about in the papers and heard about on the radio, although I am afraid my wardrobe and appearance has changed quite a bit since those early perfumed daydreams of crushed velvet and sparkling champagne! I now wear a reeking motley of dried urine, scabbing vomit, bloodstains, and tears beneath the leather straightjacket I am strapped into, my joints chaffed raw by the ill-fitting ensemble, which has only been washed a handful of times since my transfer to this sanitarium. Each time, I am left in my cell naked, clutching my knees, waiting for the conflicting comfort of its return, the nightmare between my legs screaming reminders of what I would rather forget.

With no way to measure the passage of time, every moment flutters with the familiar anxiety of stage fright as I wonder when next the cyclopean door will swing open and introduce some fresh hell. I tried to keep track of the days of my imprisonment at first, tallying the meals that passed through the sliding food tray in the metal door – but, as the meals became less reliable, and as I was shunted from institution to institution, I gave up the pursuit and forgot time entirely, existing in a sort of perpetual night that even the shrieking inmates on either side of me cannot penetrate.

Being in solitary confinement, I am in my cell for twenty-three hours each day, giving me only seven hours each week, if I am lucky, to remind myself that others still exist beyond my four walls, padded rough and rubbery, they say, for my protection.

Thoughts collapse like a house of Tarot cards when a metallic clank shatters the silence, followed by the song of a bolt sliding home and the oil-thirsty protests of rusted hinges. When the door opens, a splash of fluorescent light from the hallway bleeds into my cell, and the shadows flee. A bar of limelight catches me in its glow as I sit up to observe the warden and two orderlies enter my concrete killing jar, the many keys and fobs at their belts serenading them. The warden sucks his teeth and says, “Stand, face the wall. Spread your legs and be quiet,” which may have carried more pleasurable significance, were it said by someone half as handsome under different circumstances.

I dry my eyes on the heels of my hands, which is to say, the thick padded mitts at the end of the jacket sleeves. When I stand to my full height and walk to the nearest wall, the orderlies back up and stare as though they

have never seen the likes of me before, though, of course, they have helped wrangle me countless times by now, their cudgels hesitantly shaking in their palms the way their own confused members surely quiver in their pants at the sight of me, shuffling before them in filthy canvas flats, and not at all click-clack-clacking as I sway in custom Guyette stilettos, pummeling a varnished stage – the sound of power. I grin at the memory, and a bruise across my cheek blooms with a flower of pain where an officer struck me the week before during an interrogation. The smirk cracks my chapped lips, summons slivers of blood to stain my smile.

The warden whistles an order and stares at me while a third orderly wheels in a rickety gurney covered in a crisp white sheet, the press marks still visible. I feel every bit of dirt and stubble that festers on me under the warden’s gaze. I want to crawl deep into the wormy wood of the makeshift bed, become to starched cotton and scratching wool of my uniform, and be obliterated.

The first two orderlies set to work, securing the belts of my jacket so that I am immobilized within a leather cocoon, wrapped into a new form, like one of the armless wonders in my parents’ traveling show. They seem almost afraid to touch me as they lower me onto and then strap me atop the stretcher; they look at me askance, out the corner of their eyes, and when our eyes do meet, theirs quickly scamper away, for mine threaten to hold their gazes and choke the life from each and every one. Restrained so brutally, my eyes and mouth are my only weapons.

“A little harder, boys,” I simper. “I can still breathe.”

Steered by an orderly, with the warden leading and an armed guard bringing up the rear, I am unceremoniously jostled from my cell and out into the winding innards of the institution beyond. The stretcher becomes my litter, the orderlies my willing carriers during the long transportation process from darkling isolation chamber to the gleaming surgical theatre upstairs.

Being bound and wheeled everywhere gives me only the vaguest impression of the hospital’s layout; to me, it is little more than a funhouse of labyrinthine corridors, chromium operating rooms, and stygian chambers. We pass the bolted doors of other solitary cells, and the men hurry their pace, urged onward by the echoing wails and lunatic laughter that makes up the depths of sanity’s Skid Row, the asylum’s rogues gallery, the sanitarium’s private freakshow.

An elevator deposits us with a rollercoaster roar on the floor where the surgeries and operating rooms loom like game stalls, all winking metal and brilliant lights. As I roll past gleaming doors of metal and polished aluminum that throw back our warped images, I wonder how I look these days. Aside from the distorted doppelgangers I glimpse in the reflective surfaces of stainless-steel medical equipment, or the rain-streaked twins I spy in darkened windows that the night transforms to mirrors, I have not beheld my reflection in months – imagine telling my adolescent self that! She would have laughed and thought, Soon, I won’t need a mirror to see my image, for it will be plastered on every billboard and shining atop every marquee before long! The doctors insist seeing it will only make me worse, fretting over my reflection as I do. And perhaps they are right; after being caught, I knew nothing could ever be the same. The mane of autumn-auburn curls I once threw back with a rehearsed laugh and pearly grin were shorn off right after my arrest, strip-search, processing, and delousing. My head has been kept in an ivory dome ever since so that I cannot, in the words of professionals, “fixate on any latent femininity.” They have even kept my hormone regimen from me since the incarceration. The withdrawals were the worst part, at first. I would hold my knees and weep as nausea washed over me like low tide. Eventually, the physical pain subsided and made room for a more unique terror as subtle changes began to take hold of my body, reverting the role I had been playing for so long back into the part I had been cast in, all those years ago, the one I would rather die than be made to assume once more.

At the end of a long hallway lined with screams, the orderlies set my gurney into standing position and wheel me, like a dolly carting props, into the sterile white throat of the surgical theatre.

Backlit by blinding fluorescents, the medical center’s administrator and two nurses look like cardboard silhouettes in the spookshow, featureless, still, and blank, coming to life only when I am wheeled in and parked at the back of the room. With its humming machines squatting like steel titans and the shining equipment glinting with ill intent, the operating room resembles some cinematic medical monstrosity designed by Strickfaden. The glaring lights make my temples throb – the first pop of a photographer’s strobe in the dark.

The nurses begin turning dials and adjusting switches on a small rectangular box, which they set on a folding table beside me. The label on the machine reads “Convulsator III,” each numeral fashioned like a bolt of lightning. My stomach knots into a great length of magician’s scarves, colorful lassos of addled nerves, as the realization of what is about to happen falls upon me like a curtain call.

Walking with the jaunt of a talker about to mount the bally platform and deliver his pitch, the administrator circles and appraises me, button-black eyes flashing behind the wire-rimmed spectacles he wears halfway down the bridge of his nose.

“Patient 426-9B.” He scans a sheaf of papers a nurse hands him, signs a few documents with a flourish. “Appropriate Mr. Moonchild,” he says absently as he thumbs through my psychological report yet again, not looking up once to see the glare I am sending his way, sharper than any surgeon’s scalpel. The straightjacket is unlocked and peeled off of me, then dropped to the floor like a shed snakeskin, like a striptease in a smoky cabaret…

For a moment, I am back on stage, solar flare of the overhead fluorescent tubes providing my limelight, the gathered medical professionals my eager audience. I numb myself to the indignity of being belted and cuffed to the hospital bed by remembering the manicured handful of years I spent as a renowned vedette, lounging in silken boudoirs, sipping cocktails while crowds gathered to hear the words careening from my painted lips, or to catch glimpses of bare thigh as I danced my diaphanous layers off to reveal the confusion beneath. My head fills with the thunderous concussion of applause, the midnight chorus of wolf-whistles and cat-calls – but it quickly dissolves into the chuckle of handcuff chains and the smack of the administrator’s soles against linoleum as he checks the electroshock therapy machine and nods in approval.

Reality is a rubber chicken to the face.

“Sexual deviance. Suicidal tendencies. Transvestic fetishism. Autogynephilia. Borderline personality. Delusions of persecution. Nymphomania. Dissociative identity. Manic-depression. Violent psychotic episodes. Multiple homicides.” He finishes the laundry list of clinical labels and frowns deeply.

“At your service.” I give a snide smirk that sends a shiver of tenseness through the trigger fingers of the armed officers.

The administrator slaps my file closed and hands it off to a nurse. It is as thick as my wrist, bristling with addendums and dog-eared pages, protruding tabs and papers that the years have yellowed and worn around the edges – my dossier, more valuable in these institutions than one’s birth chart in a fortune teller’s caravan, and undoubtedly filled with twice as many fabrications.

All at once, the nurses are upon me, securing my wrists and ankles, strapping my torso into place on the operating table without a care for how much they dig into my skin or how little I can breathe. When they are

finished, a ball gag is forced between my jaws, and the electroshock helmet is slid onto my head, rendering the movement of my neck impossible. One nurse slathers translucent gel onto two electrode pads at the end of snaking wires and sticks them to my temples. An orderly scans a clipboard and tosses sour glances at me with every box he checks. They step away once they have finished, and the administrator gestures toward my prone form.

“Ladies and gentlemen, Mr. Venus Moonchild,” he says slowly, as though sampling the flavor of my name and finding it not to his liking. He stands back so that everyone can gaze upon me, bound and gagged, arms stretched out at my sides like some sadomasochist’s tableau of a crucified transsexual Christ, wearing a crown of cables, detractors gathered around to watch her degradation.

For a moment, it is like a glass of cold lemonade in summer to hear my name instead of my identification number, but, the satisfaction quickly fades when one of the staff behind him whispers the nickname that a newspaper coined for me when my story first broke, like a fist through glass…

“The Carny Killer…”

There was some confusion at first as to whether I was a rube killing carnival workers, or a carnival worker killing townies… or even a carnival worker killing other carnies. None of these suppositions were correct, of course, because what happened was far stranger than any plot conceived of in a journalist’s office or even inside the imagination factory of a Hollywood studio. Nevertheless, I hear rumor that someone was pitching a sensationalistic script about my life to executives at M. G. M., to which I could only say, “Do you think Garbo is too old to play me? I really think my life may be interesting enough to make her reconsider retirement!” Of course, the doctors all seem to disagree, attributing the recollections of my life to delusions of grandeur, my imagination overcompensating where reality failed.

But questioning my mark on popular culture is a fool’s errand; not only is my name remembered by so many, flashing in marquee lights or lavishly painted on a canvas broadside, but it is also known in the incandescent operating theatres of hospitals, in the sound-proofed rooms of psychiatrists, in the caged darkness of police precincts. It hangs in the air, like a cloud of cloying perfume, a misnomer for madness. Like legends that grow in power and detail as they are recounted from person to person, my name and reputation have been indelibly tattooed into the flesh of bizarre Americana – always far easier for the rubes to see the fearsome freak than the frightened girl beneath the sideshow skin.

Even locked away, like a waif in her deadly blade box, I manage to intrigue the public – perhaps now more than ever, being so out of their reach as I am after the opinions of doctors and the hyperbole of the press have transformed me into this vicious caricature of a mad femme fatale. But so few know who I truly am underneath the veneer of tabloid gossip and greasepaint – or who I used to be.

Once, at the height of my career, I received nearly three hundred fan letters in a single week! Now, the mail I am sent is sifted through before being delivered to me. I have an hour each day to read and respond to what I can, sacrificing my time in the crabgrass yard outside, where the male prisoners wait with malice shifting in their eyes – but, as my family taught me, your fans always come first!

Though sadly, the mail I receive these days cannot be called fan mail so much as the ephemera of thrill-seekers. Still, I read every letter, look over each card, and always reply, slashing my autograph across the bottom, the asylum letterhead always printed at the top, my signed portrait conspicuously absent. Journalists send me interviews, and psychologists mail me questionnaires, each hoping to publish something exclusive and hitherto unknown about the killer carnival freak. Aspiring psychotics send me their hallucinatory ramblings, full of their dark dreams and desires. Sometimes, a marriage proposal finds its way to me, written by men who seem to be replying to a lonely-hearts ad I never placed. My favorites are always inquiries from concerned transsexuals about hormones, surgeries, how to perform the role society expects of them, which is, to be invisible. They often implore me to write an account of my life, to chronicle my transformation and give my own version of events, free from the embellishments of the gossip columns and the diagnoses of clinicians. In a way, I suppose that is what this will become – my life story, scribbled onto lose scraps of envelope and newspaper. Of course, in typical Moonchild fashion, events recorded here will be more histrionic than historical, more manifesto than memoir. Like the pitch cards I once sold with my glamour portrait printed on the front and a fabricated life story on the back, this stack of papers may look innocuous, even tempting, but, once you get a glimpse beneath the surface, the details may, as we say in the business, shock and amaze.

I owe a great deal of the continued public interest in me and my so-called crimes to the newspapers, whose eye-catching headlines, shrieking in bold, could put even a carny’s grandiloquence to shame: “The Moonchild Massacres!” one paper screamed.

“Sideshow He-She at Center-Ring of Circus Slaughter!” another declared.

“Tales of the Transvestite Terror!” some promised.

One intrepid reporter was there, that bloody autumn night when everything unraveled, when the curtain came crashing down. The morning after, she ran a photo of me on the front page of her gossip rag – the last night I wore cosmetics, captured forever, like a pickled punk suspended in formaldehyde. The photograph shows me being handcuffed and forced into the back of the police cruiser, my makeup smeared, hair a cyclone, family watching from the shadows as I make my second daring escape from the show. My face is tilted away from the camera, lips in a snarl, as though telling the paparazzi, “No photos, please, unless they are from my best side!”

“Eleven o’clock in the morning. Patient 426-9B, Venus Moonchild. Aged thirty-four. Caucasian. Height, five-ten. Eyes, blue. Sex, male, though the patient denies it as a symptom of his autogynephilia.” The administrator speaks into a recording device held by one of the orderlies as he paces around me. “Today, we are here to conduct an electro-convulsive therapy session on Mr. Moonchild. We will be starting with eight-hundred milliamperes of current administered bilaterally. Patient has been appropriated. We are ready to begin.”

I glower at the administrator, wishing a good beam of key light would strike me across the eyes. Instead, the blinding light of a lamp directly in front of my face crackles to life, and I find myself drowning in a snowstorm I can feel in the roots of my eyes.

Over the last four years, I have endured every barbaric torture that the medieval world of modern medicine could possibly conceive: hydrotherapy, sodium amatol and pentathol, Metrazol, pulse monitors, polygraph exams, caning, starvation, sleep and sensory deprivation…but nothing like this. Many times, I feared I would never make it back to the safety of my cell.

My first month here, a run-of-the-mill interview led to a violent waterboarding experience when one of my wisecracks hit a particularly raw nerve in the interrogating officer. I was restrained, cellophane wrapped tightly around my face like the packaging of a Christmas present. A steady flow of water flooded my senses as nebulas of indigo and ebony blossomed at the corners of my vision, swallowing up the light like great greedy handfuls of night. I slipped into the darkness as easily as a warm bath and woke in my cell, constellations swarming my vision for hours after. Never again did I offer an officer a night in my cell in exchange for freedom!

Standing next to my head, the administrator stares down at me, the corners of his eyes as crinkled as old playbills, his mouth a nicotine smile.

“This therapy has proven successful in the treatment of schizophrenia, clinical depression, and female hysteria, as well as sexually-deviant disorders, such as homosexuality and transsexualism. Our hope here today is two-fold: that Mr. Moonchild will recover memories of his crimes that may be useful to authorities, and that, in the process, we may correct any faulty wiring that may be present.”

His voice is lost as the machine whirs to life, the sound of arching electricity burning away his words. I feel pearls of sweat embroidering my hairline, running between my shoulder blades and beneath my breasts. One of the nurses turns a dial, and the room blurs like a watercolor painting left in the rain. With a symphony of electrical zaps shredding the air, my body tenses, goes as rigid as a plank of wood, anticipating the shock to come. But, in the last moment, a fleeting memory flashes in my mind’s eye – the patients in my position who have resisted before, their bones broken, flesh bruised and burnt. I go limp as a discarded puppet, and just in time.

The first shock hits me like the sledgehammer in a test of strength.

A serrated tremor ricochets about my head, then bolts down my spine before sizzling like pinpricks along the highways of my nerves and throughout my extremities. My muscles go taut as wet rope, and my body convulses upon the slab. The belts bite into my arms and legs as I ride the seizure. Slowly, the lightning releases its hold on my body, slithering out of my trembling limbs, and I shudder like a loose broadside in the breeze.

There is a moment of silent stillness where all I can feel is the cold fire in my head. Everything else has been lost in the sterile snowstorm of white tiles and cotton balls and starched medical jackets. The second shock surprises me, crackling through my skull, pulling shivers from my core. The ladder of my spine blazes and radiates outward. My fingers clutch as the rough sheet beneath me, and I do not even notice some of my nails breaking off at the quick. Nausea simmers in my gut, and foam runs from the split corners of my mouth as the current is shut off once more, though the incessant ringing and popping continue to shatter my eardrums as the hazy room sways around me, briars of lightning filling my skull.

The administrator turns the dial a third time.

If I were performing, say, as Electra, the Electrified Girl, this would be the moment for my death-defying escape act. I would find a way to slip the cuffs and prance across the stage, improvising a striptease with the harness and headgear as the administrator and nurses made comedic chase. But I am not an escape artist. I have never been, and this act will not end with a bow, flooded by applause.

My mind is reeling like an errant pinball with the wrenching blow of this final shock. The hum and drone of the machine begin to fade and, in its wake, I hear the sound of gentle clapping, a muffled voice shouting in the distance, only the troughs and crests audible in the distorted soundscape of memory. A dazzling light erupts behind my eyes despite them being so tightly shut and, in the smoldering haze, I find something familiar waiting for me.

Inside my electrified nightmare, an internal velvet curtain rises. A brash fanfare honks and brays, sweeping into a revelatory crescendo. I can smell the sawdust beneath my feet, the familiar potpourri of grease, burnt popcorn, and manure.

I stand in a sea of flapping canvas, stripes of red and white, like scars in flesh.

With bated breath, I wait in the wings for my cue.

It shocks me when it comes, amplified through the talker’s megaphone, casting all else away. “And now, ladies and gentlemen, boys and girls, brace yourself for a most peculiar act…” The story of my life.