Henry loved the way the flowers sang.

“They sound like wind blowing through an arctic canyon,” he said. “Like a children’s choir. But a good one, you know? Not cheesy.” His head lay on my chest and he pushed it into my hand, asking me to keep playing with his hair while I tried to imagine a non-cheesy children’s choir. “They sound like outer space.”

“There’s no sound in space.”

“I know. Like things in space should sound. Nebulas, star clusters. Use your imagination, Edward.”

I played with his hair and with my other hand traced down his shoulder, over the curve of his bicep, as the weird, dissonant song drifted in through the open window. I hated the flowers. All summer, every damn night they made their racket down in the storm drains, pale green petals opening wide, exposing gaping mouths that issued the noise people liked to call “singing.”

“It’s not even singing,” I said. “It’s digestion.”

“What?”

The plants were some biohacker’s joke, or maybe a bad idea hatched one night over too much weed. Seeds tossed down a grate, scattering in the filth and the muck, finding a crack to root in. They liked it below ground. They were engineered to.

“Plants expel methane.” I leaned forward and kissed him, once on the neck and once on the ear. “I read about it. These just save it up and do it all at once. That sound you love.” I paused, cocking my head to listen to the more or less constant keening outside. “It’s a bunch of flowers farting.”

With an exaggerated sigh, Henry flipped over and got on top of me. “You try to ruin everything,” he said.

*

When Henry got sick, it happened fast. Or maybe it happened slow and we took too long to react. I took too long.

“My stomach is off,” he’d say and skip a meal. When it happened a couple of days in a row he’d lay with his head in my lap and I’d rub his soft belly in slow circles and suggest he go in and get it looked at. Then it would get better. A week would go by, no complaints.

One night he was brushing his teeth with the bathroom door open, bare-chested, hair a mess. He took forever doing all his bedtime stuff and I watched him in the dim light, hands basketed behind my head, waiting for him to come to bed. One of my great pleasures. He leaned forward to poke at something in his teeth and I realized with a start I could see his ribs. When he slid into bed and nestled beside me I made him promise to call his doctor in the morning.

A few hours later I woke in a drenched bed with a feverish Henry humming tunelessly along with the flowers.

*

“Acute myeloid leukemia,” the doctor said. We sat in her office for a half-hour as she talked about treatment and Henry’s prognosis. She spoke about the late stage he was in, his limited options, white blood cell counts, so many things. It was a windy day and a tree kept rattling the window behind her. There was a piece of lint in her dark hair, standing out stark and white. Henry spoke to her in clipped tones, all business, like his brain had been hijacked by aliens. I don’t know if I said anything.

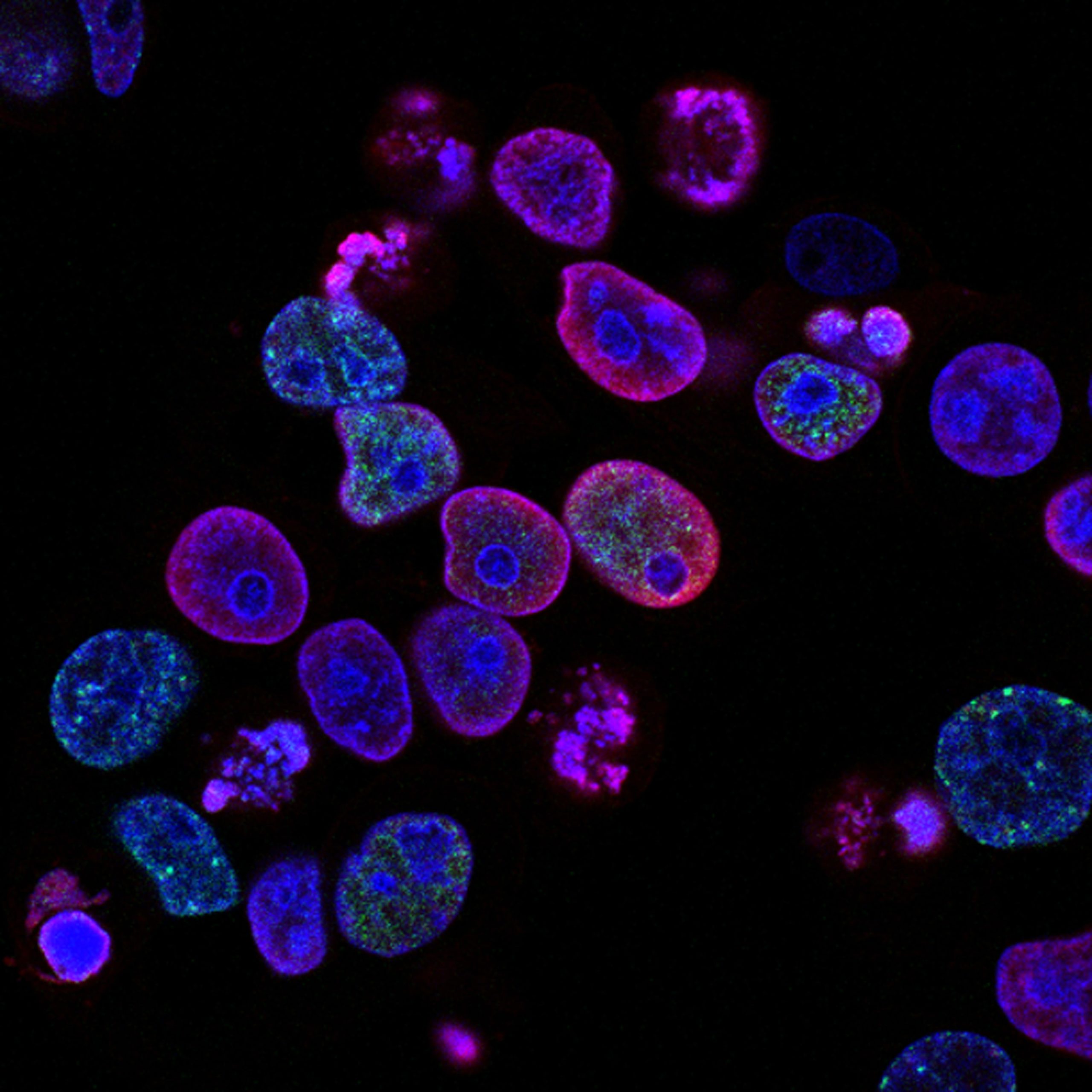

They injected him with bio-engineered pseudo-cells. “Cancer killers,” the doctor said. “Much better than the hit or miss treatments they used to do in the dark ages. They can reproduce, learn and adapt while inside the body. Made specifically for Henry.”

“My tiny heroes,” Henry called them later.

“With little swords,” I said, giving the pasta a stir. “And microscopic armor. Some of them have maces probably, or halberds. Whatever a halberd is.”

“No.” Henry leaned against the counter, the dark circles under his eyes contradicting his soft smile. “They’re from the future. Spacesuits. Armed with science. Those are the guys I need.”

The weather cooled as we slogged through autumn into winter, and the flowers stopped singing. Henry was always tired but his blood work looked good. If I woke in the middle of the night, my heart pounding with anxiety, I always found him in bed beside me, sleeping, breathing quiet and steady.

*

“My head hurts.”

Henry frowned at me across the table, his fork hovering above the salad he’d barely touched. He pushed his glass of wine toward me. “Here. I’m not going to finish this.”

I dumped the wine into my own nearly empty glass. “I’ll always be here to finish your wine, never fear.” No grin. Instead, he winced, his face pale in the dim light.

That night he threw up several times, arching his back on his hands and knees, muscles straining, his voice reduced to a harsh rasp by the time he was done. He slept fitfully for an hour or so, his sweaty head tucked against my chest before I got him dressed and took him to the hospital.

*

I came home a week later with a plastic bag full of Henry’s clothes, some unread magazines, and his wedding ring. Our dirty dishes were still in the sink, and the apartment smelled stale and pungent with old garlic. I went from room to room opening all the windows and lay down on the bed, pinned there like an insect in some careless child’s collection, dusty and forgotten, left to endure a slow disintegration.

Time passed. I know this because it got warm, and even though I’d taken leave from my job, I still had to fend off calls from family and friends. None of it touched me. I shoved their love, their care, into deep places from which I’d severed all ties. Still, they tried to draw me out.

“It’s spring, Edward,” my sister said. “Take a walk in the park. Please.”

“Sure. Maybe tomorrow.” I stared at her sitting on the couch in her living room, legs tucked beneath her, the holo set to life-size, so big it took up half the bedroom. My end of the visual was shut off. She couldn’t see me lying on my stomach, arms dangling from the bed listless and pale, the half-grown beard that had sprouted patches of gray, seemingly overnight. “That sounds like a great idea.”

*

The flowers woke me from a dead sleep a little before midnight with their first song of the year, long drawn-out notes ruined by sour harmonies that made my teeth clench. Nights were bad. I’d lay awake for hours clinging to my side of the bed, unable to take the rest of the space for myself. The fact that I’d fallen asleep at all was a miracle. And they fucking woke me.

I found myself dressing, then stuffing my feet into my shoes by the front door. The street was empty; if the flowers bothered anyone else they kept it to themselves. No moon. They were loudest when it was dark.

I followed the sound of the singing to a storm drain with a gap between the street and the sidewalk just wide enough to slip inside. I went in feet first, scraping my shoulders and arms. I crouched low, my head brushing the ceiling, and when my eyes adjusted I could make out a circular hollow with passages branching off. The singing came from straight ahead. I shambled forward, feeling my way, the rough stone of the passageway growing damper and colder. I didn’t need a light; I had the noise to guide me.

It grew louder, denser. The cascades of notes crashed against themselves, echoing off the walls, repeating over and over, numbing me with the relentless onslaught. The stench got worse as well. I gagged on the thick air, trying not to imagine what might be passing through my lungs, and doubled over, dry heaving. When had I last eaten? There was nothing to let out.

I came to a wider chamber with water trickling in from narrow pipes on either side, forming a dark pool. There were rungs leading down and it reeked of rotten eggs and an awful sweetness. I couldn’t tell how deep the water was, but the flowers were somewhere beyond it.

I climbed down the rungs and hesitated, my foot just above the oily looking surface of the pool. I remembered Henry’s sunken eyes as he lay in the hospital, the bones protruding from his ravaged body, and I plunged in.

I splashed and sputtered, trying to keep the muck away from my face. I kicked against something—maybe the bottom of the pool, maybe something else—then pulled myself up, tumbling onto the slimy ground with the awful singing rattling my ears. I sloshed forward, following the tunnel, rounded a curve and stepped into a huge, open chamber.

They were everywhere. Thin, green shoots protruding from the soft muck with dagger-shaped leaves sprouting every few inches. The biggest were waist-high, their long petals opening wide to reveal sickly pale orbs, featureless and smooth, like the blind eyes of cave fish. Most of the orbs were turned in my direction as if accusing me of surprising them in the dark. The tumult was incredible. High-pitched overtones wavered from whistling and breathy to painfully sharp. I wished I’d brought something to plug my ears. But it didn’t matter now.

I grabbed the closest one with both hands and ripped it from the muck. The roots, yellowish-white and spattered with filth, looked so vulnerable dangling naked in the air. I flung it to the ground, crushing it beneath my shoe. I moved to the next one.

I waded through the flowers, zigzagging across the chamber, pulling them up and tossing them aside. Some resisted, holding fast no matter how hard I pulled, so I kicked them over or tore off their heads, imagining the pummeling din to be screams of terror and remorse, and for a few minutes I was suffused with a kind of angry joy.

It made no difference. I tried, and my hands, stained green and slick with an oily substance, ached and cramped. The singing of the flowers was as loud as ever. There were thousands of them in the chamber and they lined the nearest passage thick as grass, disappearing into the darkness. I’d barely made a dent. I fell to my knees.

You try to ruin everything.

“I know.” I could barely hear my voice there amongst the flowers.

*

It was quieter at the apartment, even though there was still some singing in bits and snatches coming from underground. Winding down for the night. I stripped off my filthy clothes and threw them in a heap by the door, stuck the bunch of flowers I’d brought back in a pitcher of water, and set it on the counter. They drooped, a bit worse for wear after all they’d been through. I turned off the lights. They seemed to straighten, the pale orbs facing upwards. A trick of the dark.