Chapter Two

My father had been obsessed with making sure I knew how to tell when and where an animal had been. When he was whipping his little Toyota truck, which he lovingly called The Yoda, up the side of a mountain, speeding around corners with no guard rails, he’d screech to a stop next to some tracks or scat.

“Whadduya see, Levi?” he’d grunt, reach over to the passenger door, throw it open. He’d lean over, ignoring Sage, sat between us, knowing she wouldn’t know anything.

I’d poke my head out to observe the tracks or the pile of animal shit he wanted me to look at. Grunted back the right answer, waited to see his face light up, his yellow-green eyes shimmering.

“That’s my girl. That’s my Shithead,” he’d yelp, grabbing the scruff of my neck, shaking it firmly. “Very good, Levi. Very good.”

Once, on the very same drive to the Wiley house, he’d spotted a coyote across the river. There weren’t any close exits, so he’d pulled over to the shoulder, grabbed his favorite quick-draw rifle, a .220 swift, from the gun rack installed right over our heads. I remember never being able to put my head back, else cold steel pressed into my nape.

“Come ‘ere, Levi,” he commanded. He pressed Sage back into the seat, shooting her a quick look that she knew meant she was not to move.

It was early. And in Montana, early means cold. Even in the depths of summer, no matter how hot the day gets, the morning and the night are freezing. I’ve never been a huge fan of the cold, but my father seemed to relish it.

I’d gotten out of The Yoda, found my father arranging his plaid, wool-lined coat into a makeshift gun stand. He pulled some shells from his pocket, slipped them into the chamber, locked it into place. I watched from a few feet away, waiting to be invited into the space. I knew better than to rush him, than to ask questions. When my father wanted to teach me something, I was to quietly learn. Do it perfectly to begin with, or else face his wrath. His heavy disappointment. I learned to watch him carefully, store away his actions for perfect imitation.

He beckoned me towards him with two massive fingers, cracked and scarred in contrast to his youthful appearance. His fingernails were always black; he always smelled like torched metal and fresh blood. Lifting me onto his knee to stand, I set the gun in my shoulder, leaned down to glimpse into the scope.

It always begins as black. Black circles clipping over your vision, over and over again, until you’re properly adjusted. It was difficult to balance on his knee and try to see what he was wanting me to see at the same time. I was probably seven or so.

“Do ya see?” he asked, and I lifted my head, attempted to find where he was pointing. I readjusted the position of the gun, found my view again, saw the little coyote on the opposite bank, sniffing intently around the water. I took a second to watch the little guy, before I told my father I’d spotted him. Dad would have expected it to take longer anyway, so I took the opportunity to watch the coyote before I would have to murder him.

The beast’s erratic, yet careful movements, his ears pointing and repointing, reminded me of our hunting hound, Whiskey. At one point, it seemed he looked towards me, tried to see me scoping him, his big yellow eyes open and alert. Maybe he’d smelled us.

“I see ‘im” I breathed, keeping the canine in my line of sight. I felt my dad touch the side of the gun, my vision clipping for a second.

“Saftey’s off,” he whispered.

I took a deep breath in, stared the coyote straight in his eyes. I waited for him to decide there was nothing to be alarmed about, turned his head down to sniff again. I moved my fingers into the trigger guard.

The moment before you pull the trigger is always silent. Tense. Thick.

The shot echoed in the valley, jumping back over the river to reach us. My ears rang.

“You got him, sweetheart!” he shouted, muffled and distant. He grabbed me from my stance and threw me on his shoulder. “I’ll be damned. My lil Annie Oakley, over here.”

The kill brought me little joy, but I relished his attention, his approval. I wasn’t the son he’d wanted, but I thought I was doing a pretty good job proving to him that I could be better than what he’d wanted.

Dad pulled Sage from the car and said, “Come on, baby, we’re goin’ for a swim.” She found my eyes when he turned his back, throwing his leg over the guardrail. I gave her a curt nod, and using both hands, she closed the truck door. We scrambled over the guardrail, trying to catch up with Dad, shuffling down the side of the steep incline. Three mountain goats, strong stout bodies, big flat feet stepping lightly over loose rocks, thick hands reaching for stuck-out roots.

He stood waiting for us at the bottom, arms crossed, a big crooked grin beneath his black mustache.

“You’re both so beautiful,” he told us, beaming, “Shitheads.”

Turning, he took his shirt off, flung it onto the river rocks. We stood on either side of him as he eyed the current. It wasn’t slow and it wasn’t too forgiving. The Clark Fork had its soft stretches where people could float their inner tubes safely, beer cooler tied to them, bobbing cheerfully along. But this was early summer, and the water was high, and flustered.

“Grab on,” he told us, slipping off his black and red cowboy boots and stepping closer to the water.

Why can’t you just go yourself? I wanted to ask, glancing at Sage. Fear began to grip at my throat. I debated whether this was dangerous enough for me to risk a beating over. There were times when it was absolutely clear to my gut that the risk must be avoided, that Dad was forgetting our fragility as children. As humans. True danger was worth a beating to avoid.

But somehow, in that instant, even with little rapids biting at the top of the water and the breadth of the river seemingly vast, I completely trusted my father. There were times when he seemed otherworldly. Moments when I just felt and knew that he was capable of something that seemed impossible.

I guess that’s the closest I’ve ever come to faith.

In that moment, his scratched and scarred back, tan and broad in the early morning sun, his wild black hair, grown a bit too long… in that moment he seemed invincible. I slipped my boots and my jeans off, standing in my red t-shirt and underwear, shivering in the cold. Sage followed my lead, carefully propped her baby blue tennis shoes up next to each other.

We clung onto his shoulders, the cold water coming over us, taking the air out of our lungs, as he waded further and further out, kicking off from the river rocks beneath his feet, orienting himself horizontally. He shimmied his shoulders as a warning, and Sage and I readjusted our positions, coming closer together, holding onto each other with our hands meeting around Dad’s neck.

He took long, strong overhead strokes, angling diagonally to the opposite shore. The current did take us away some, and his breath got heavy. My stomach lurched every time I felt him lose control, a shoulder dipping. I swallowed my urge to voice my concern, instead checked Sage’s expression, her mouth open, fiercely staring at the shore, as if willing it closer.

He felt his feet find the edge of the bank. He began to stand up, and I expected him to shrug us off and make us swim on our own the rest of the way, but he allowed us to cling on, our legs floating peacefully behind us. I laughed. Sage started giggling.

“What’re you two geese laughin’ at?” my father said.

He shrugged us off when it was shallow enough to walk. We followed closely behind as he led us to the dying coyote. The shot had punctured his stomach. He lay pitifully in the mud and the rocks, blood collecting in black pools, coating some of the beige insect husks left on river stones to dry. His eyes did not detect us, sliver pupils looking far away into the light beyond the mountains.

Sage and I stood motionless, unable to look away from its short, painful breaths.

“Forgot my fuckin knife,” Dad snarled. His head turned this way and that, searching. He crunched off some distance to our right.

Sage and I continued watching the coyote bleed out, white tipped red and brown fur, rising and falling. Something formed in the pit of my stomach. Something wicked. It scooped out the acid, filled it with something heavy. I swear the coyote rolled its eyes towards me, looked at me. Saw me. Its lip curled back to reveal pointy, curved teeth, flecked with red, the tongue beginning to loll out.

A giant rock suddenly crashed down onto its head and crushed the skull with a sickening crack. Brain matter flung itself to the water shore, some of it swept into the current, swirling in the froth. My father stood above the mess; hands still held out, his arm muscles still strained and pulsing with the weight of the boulder. Our shins were speckled red.

Dad dusted his hands together with a hefty groan, crouched down to stroke the creature’s fur, almost lovingly.

“Don’t wanna let ‘im suffer too long,” he told us matter of factly.

He slung us back on his back, told us to hold onto the coyote between us, wanted to make something of the pelt. A couple of flies, maybe just a decorative throw. Told us the meat wasn’t much good, too tough, but we would eat some anyways, otherwise it was a waste.

Sage didn’t want to touch it. I tucked its body, almost bigger than mine, under my arm, held on for dear life, fighting the current’s will to take our kill. Its crushed head leaked more brains into the current, an eyeball hanging by a thin bundle of strings, dancing on the surface. I watched, thinking the same word over and over again, imagining it swimming in between my own brain matter, dipping and twirling and spinning.

Omen.

▲ ▲ ▲ ▲ ▲

I thought about killing him.

I always thought about killing him.

Every time I watched his chest rise and fall was torture. Those rickety breaths swam over to me, squirmed between my bones, and made me itchy.

It would be so easy to kill him.

Love and violence have become inseparable to me. The love I felt for my father consumed me, made me passionate.

I thought about how much I would love to see his blood spurt from his neck and stain the white sterile blankets and pillows until it was all scarlet and ruined. It would pour out from his neck, warm and sticky, onto my hands. He’d gleam up at me with those yellow eyes from underneath all that gore, grateful.

I don’t know why I could never imagine killing him softly, with a well-placed pillow pressed too hard. Or a few pills, hastily crushed. I guess I just thought that he would hate that. That he had never wanted to go quietly. I know I didn’t.

Flopping down into the beige plastic guest chair, I stared suspiciously at Dad, waiting for him to suddenly spring up out of that hospital gurney and admit the whole thing was a joke. Just kidding, this is a total scam, this whole thing is a big dumb joke, and you’re stupid for crying!

Fifteen minutes. Nothing. So, I guess it was all real.

“Hey, Dad,” I barked in his direction. A nurse in the hall stopped her squeaky food delivery cart to glare at me. Ignoring her, I stood up and made my way to Dad’s bedside.

The smell was first. A sickening, sour scent. Decay. Like his brain was rotting from the inside out, the degradation wafting from his ears. It mixed with the salt and grime sticking to his back, wherever the skin folded, and the ooze from the sores that had formed from nearly four years of bed rest. To me, he looked like a wrinkled-up child, small and frail with sagging skin where muscles used to be. He’d never been tall, but now he seemed shorter than me, his spine concaving, his feet mangled. The paleness was perhaps the most striking. Ashy, almost green skin.

Dad was on his side, feet and hands poked out from underneath a very fresh looking blanket. The nurse must have washed him that morning. I wondered if it had been Corey who’d sponged warm water over him, gently turned him onto one side, then the next. I wondered if Dad remembered him, from the few times they’d met when we were high schoolers, before the illness got terrible.

I traced the IV from Dad’s hand to the whirring machines, bedside, keeping track of his heartbeat, and a bunch of other statistics I didn’t understand. The nasal cannula was poised precariously under his nostrils. He was always trying to rip it out. To my utter horror, I noticed that he was wearing a diaper. I reared back and dug my nails into my scalp, dug until I could feel them break the skin.

Stifling a scream, I bit into my hand and willed myself not to kick over every fucking machine stuck out of him. I could snap those tubes with my teeth, could drive the heel of my boot down into the green lines of life sizzling across that cursed black screen.

I recalled the last time I’d seen him, four years ago. I’d come here fully prepared to say goodbye for the last time before I left. But somehow the bastard was still kicking.

“What do you want?” I hissed, my face inches from his, “Why won’t you go?”

He stirred, opened his big yellow eyes, set so very far back in his head. His chapped lips opened, eyebrows struggled to raise, hands started to shake, first slowly, then with increasing energy. Soon they began flailing, this way and that, out of his motor control. The disease ate his spinal cord, too, fried the connection to his limbs and throat. I stifled my fury, reached for one of his hands, clasped it in mine, held it still for him, battling his weak body.

“Daughter,” he rasped.

I nodded. He stared into my face, into my eyes, trying to find me in his mind.

“Marie?” he asked. I shook my head.

He often confused me with Marie. My father’s second wife had had three children with him before she finally left, and Marie was the eldest of them. When I’d left for college, I’d stationed her like a general in their household and had her relay the necessary information about the younger ones to me over crispy telephone conversations in dorm stairwells. There was another child out there too, Thomas, in California with his red haired mother, the third baby momma. He looked the least like any of us.

Marie had done a wonderful job. I relinquished a lot of my eldest duties to her during my college years, and stepped into more of a semi-absent father role. Sage became the mother of all the mothers.

I understood why he confused the two of us, Marie was a mini-me. She’d even dyed her hair, recently, to be light, just like mine. She was also small, athletic, with big hips and fierce eyebrows. And we all had Dad’s eyes. Every single one of us.

Dad looked away from me, his whole body shaking. I realized the movement was hard for him, but he was determined to remember me. I wished he wasn’t. I was hoping my time away would have forced him to forget me, then maybe he could have left, by now. I fought another of his arm spasms, flexed against his pushing hand. It stayed. He turned back to me.

“Levi,” he gasped, eyes even wider, mouth trying to squirm its way into a smile. His teeth were jagged and black. All the meth and hookers were catching up to him, souvenirs of his final years of mobility.

“Levi,” he cooed.

I glared down at him. Everything felt hot. I thought about killing him again. This time I yanked the oxygen tube from his nose, wound it around his neck, threw a leg over him, pulled at both ends of the tube until his windpipe cracked. He would struggle beneath me, faintly smiling, cough blood up onto my cheeks. Then we’d lay in the aftermath, him no longer twitching and me huffing.

“Yes,” I choked. I turned my face from him, felt the tears coming.

“I… love… you,” he said, every word a task.

“I love you, too, Dad,” I whispered, the tears bursting through. I’d almost called him Daddy. I suddenly felt so young. He’d never allowed the boys to call him that, only the girls. And I’d made sure he’d never classify me as female, never wanted all the bullshit that came with that label in my family.

Dad’s eyes didn’t leave my face for a few minutes. I knew he loved to look at us. All of his beautiful children, his legacy. Sometimes, all of our mothers got together and had drinks and talked about how the only thing he was ever truly good at was making beautiful babies. Smart babies, strong babies, stubborn babies. We’d all turned out surprisingly well. So far. Probably because my father had a knack for ensnaring innocent, intelligent young women who didn’t know any better.

In his prime, Dad was capable of talking people into nearly anything.

Once, he’d been arrested in Superior. A common occurrence. He’d been a fan of fighting, drinking, and driving, throwing his beer cans out the window, trying to land them in the bed of his truck. A squad car had picked him up on the East side of town, blaring drunk, knife fighting with the bartender over whether or not he’d already paid. By the time the police cruiser rolled over the bridge across the lazy Clark Fork and made it to the police station, the son of a bitch had convinced the cops to let him go. He’d told me the officers were apologizing while they took his handcuffs off.

Dad liked to embellish.

I’m sure the indents on his wrists hadn’t even disappeared by the time he’d made his way right back over the bridge, through those swinging saloon doors, onto the same red vinyl stool at the end of the bar.

“Wah,” Dad rasped.

My thoughts snapped back. Back to his gaunt face, the pressure of his flailing hand in mine. I found his eyes, waited for him to make more sense.

“Ter,” he said, moving his eyes down and to the right.

I followed them, found a metal bowl of water, with two star shaped sponges stuck on sticks, soaking, blue and yellow. I took one out and placed it at his lips. He popped it in his mouth, struggling, clamped his tongue and the roof of his mouth together to press the moisture out of the sponge. I gave it a gentle tug, he let go. I dipped it back in the water, repeated the process a good five or six times.

“Levi,” he said, refusing the dripping star in my hand by keeping his lips closed a second longer than usual. “I… love…you.”

“Love you too, Dad,” I told him again. He nodded, satisfied. I placed the star back on his lips, and I helped him finish the bowl of water, one sponge at a time. Every now and then, he interrupted to tell me he loved me. I knew he wanted to say more. I knew he wanted me to want to be there, to talk to him, to enjoy his presence. But we both knew I didn’t.

So we just loved each other.

I left to refill the bowl in the bathroom, left the sponge sticks on the side table, resting on a napkin. I could feel his eyes on me until I shut the door, clicking softly into place. Sitting on the toilet lid, the bowl in my lap, I cried for a little while. Quietly.

Tossing a tissue into the trash bin, I flung the door open, fully prepared to rush my goodbye and head out. I found myself frozen in place, feet stuck onto the tile just in front of the bathroom.

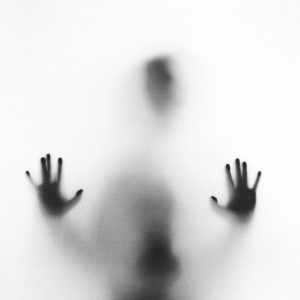

On the edge of the hospital bed sat an enormous coyote, sat up right like a human, coy face angled towards my father. His limbs were elongated, man-like, with fur drooping off elbows and ankles. The space around him appeared to be stretched, pulling at the seams of the air, shifting and settling as if in constant transition, like reality wasn’t sure if he was there or not. He dragged two of his claws gently across Dad’s forehead, down his cheekbone, under his chin, down his neck, and stopped at the collar of his hospital gown. The coyote pinched the thin fabric between his claws, dropped it, flung it away from him, displeased.

Then, without turning his face, he rolled his slitted yellow eye away from my father’s face, landing on me, his pupil dilated, consumed the iris. Lips peeling away from gums, the coyote flashed me a wicked smile, his teeth and tongue wet with saliva.

“I could do it for you, you know,” he said. But his mouth didn’t move. The voice didn’t come from anywhere. It came from everywhere, low and crackly, as though a fire were talking, echoing.

The coyote shifted himself and fell off the bed onto his hind legs, claws clacking onto the floor. I stood completely still, heart racing, unsure of what to say. He made his way towards me, every footstep purposeful and slow, tongue rolling from one side of his face to the other, licking up the salivation on his teeth. I swallowed, clenched my fists.

“Do what?” I rasped.

Suddenly he was right in my face, snout pointed down, ears perked up completely on top of his head. The pupils were constricting and dilating so quickly, over and over again, skimming over my face and body. I felt his tail brush my hand, but I knew better than to look away from him now.

“Kill him,” he said, emitting a chuckling sound, guttural. We stared at each other, his pupils dynamic. I could smell him. Dirt and blood and pine. He lifted a claw to my face, placing it on my bottom lip. I pushed my fear down as he growled, almost a moan, desperate; his teeth pushed their way into view again.

He pulled on my lip softly, mimicking the movement I’d just seen him do to my father, claw halted at the top of my sweater. He tugged at it, gently.

“Levi…” I heard Dad say, reaching a flailing arm towards us.

“Sleep, fool,” the coyote said, waved a lazy paw at him. My father fell back onto his pillow, his body entirely still, eyes snapped closed.

“How did you get in here?” I asked.

“I walked in,” he told me, grinning, tail brushing against me again. “So, what do you say, Lovely Levi?”

I dared to venture my eyes towards my father, away from the coyote. Dad slept peacefully, his breaths, for once, not so laborious, the machines cheerfully bleeping along.

“I could take this all away for you,” the coyote sighed, reached to push a strand of my hair behind my ear. He wasn’t gentle enough, his claw drew blood, from the middle of my cheek to where my ear began.

I saw him smell blood, saw him see it, pupils wild and frenzied. Teeth clacking together, he lunged his hand towards me, grasped me around the throat, leaned his snout towards me. His tongue curled out from behind layers of teeth, pulled itself across my skin, tracing the cut, lingered near my ear. I shivered, unable to resist the raw panic.

“When?” I whispered into his ear, now so close to my mouth. He tilted his head in, brushing his ear against my cheek, as though trying to suck my words into his ear canal. He pulled away to observe my face; his mouth opened wider. I saw that he had more teeth than most coyotes, two or three rows beyond just the first.

Abruptly, he pulled away, his ears spun this way and that, jaw clicked closed, pupils became still slits, looking beyond me. He slowly moved his paw from my throat to my shoulder, down the length of my arm.

“Soon,” he said, his voice sober. He twirled on his toes, strutted to the window, threw it open. Turning to look at me, once more, he grinned, gaze lingered on the cut he’d made, traced it with lust. Maneuvering back to four legs, his form became smaller, his body less humanoid. The air stopped pulling around him, settled calmly around his paws and snout. He leapt out of the window in a brownish-red blur.

“No more visitors, for now, sweetheart,” a mousy voice said over my shoulder. A woman who looked too old to work bustled into the room, shooing me out.

I stumbled back to my truck, with hardly a glance back at my father, heart pounding. Corey grabbed at my arm on the way out, asked if I was okay. I threw him away from me. I locked my truck’s doors and wildly searched for the fiend I’d just met. I thought of Coyote’s grainy tongue, dragging across my cheek. His hot breath still lingered on my skin, sticky.

Pulling down the sun visor, I flipped open the mirror, addressed my appearance. My face was a mess of mascara and blood. Realizing I still had to get to the Wiley house, I began to reassemble myself, dabbing at the cut, trying to stop the bleeding. Quickly, I gave up, pulled the bun loose, to cover my cheek with a curtain of hair. Just as I was finishing up, the reflection of my truck bed in my rearview mirror caught my eye.

No coyote.