The cigarette smoke feels like fire, searing holes into Cal’s brand new lungs.

Lungs that are still fresh from the culture vats, that have barely tasted their first breath, and he just flooded them with nicotine. It feels good. Like he’s making the loaner his own.

“Use of addictive substances is illegal in government-issued organics,” the virtual therapist intones. “Remember: you are a custodian of taxpayer-subsidized—sidize—dized—”

The therapist’s voice skips, warning symbols flashing where its pupils had been. Its body wavers and fizzles as Deion disconnects the projector’s ethernet cable, leaving a floating error message in its place, imposed on a slow-rotating Selective Service emblem.

He tosses the cable aside and motions for Cal to continue.

“I saw myself again.” He coughs through clenched teeth, his vision blurring with tears. “Last night.”

Ten dead-eyed doll faces nod back at him, arranged in a circle around the shelter’s main room. For a moment, it’s silent, except for the clearing of throats, the clicking of lighters, and the creaking of chairs rocking on their back legs.

“The derealization will do that to you,” a voice — his voice — all their voices — answers. “It gets better with time.”

One of Cal’s spindly hands curls into a fist. “It was me.”

“No, it wasn’t. You know that.”

He lifts his head, trying hard, and failing, not to see their faces. His loaner’s face, reflected back at him from ten different angles, beneath ten different patterns of illegal tattoos and self-inflicted scars. No matter how they distinguish themselves, the same canvas of slick, synthetic flesh shows through.

One of them leans forward. Venditti, judging by the shaved head and the Orthodox cross, inked at his throat. The single chair between Cal and him is empty. Bobbin’s old seat.

“Walk me through what happened,” he says.

Cal does. He describes the fleeting glimpse of his face drifting through the crowded bar, how his heart stopped, and he vaulted the pool table and chased himself out into the street, where he watched himself slip around a corner and disappear. But in that instant, he was convinced it was him, absolutely certain—

“That wasn’t your body,” Venditti interrupts and the nine others murmur in agreement. “Ghosts are a symptom. Best thing to do is ignore them.”

“And avoid familiar places,” someone else chimes in. Textbook advice, straight from the government manuals. “They make it worse.”

That’s always their answer, Cal thinks: chalk it up to the symptoms and move on. But he’s seen ghosts hundreds of times — reflected in puddles on busy streets and in grimy subway windows and sometimes hovering in the darkness of his bedroom — and the illusion never lasts more than an instant.

This one stayed real long enough for him to chase it. Long enough for him to know in that visceral way he once knew his own reflection.

Venditti squeezes his shoulder. “Cal? You understand, right?”

Bright sparks of pain prickle at his loaner’s fingertips, but it takes him a few seconds to notice. The cigarette has burned down to its filter.

“Sure,” Cal lies, tossing it away.

###

Last time Cal saw his own flesh, he was watching soldiers load it onto a truck from the front seat of his ’27 Dodge.

They came one by one, that latest batch — dozens of limp, lifeless forms, sliding around naked in their vinyl casings. A steady stream of drone fodder, straight from the splicing rooms.

Cal laughed to himself as a lone sack slid off the truck, tumbling to the tarmac. But the laughter died in his throat when he recognized it. That mane of greasy hair, those wiry limbs, the imperfections of a face he’d agonized over countless times in his bathroom mirror — those fuckers just dropped him.

The last emotion he remembers having was rage, white-hot and futile, at the sight of his body treated like any other piece of war meat.

There was no use in fighting, though. Cal knew the consequences for loaners who resisted. He was a custodian of government-issued organics, and what was given could just as easily be taken away.

As he tore out of the parking lot, the soldiers tossed his body back into the semi and slammed the doors. Billboards staggered along the access road thanked him for his contribution.

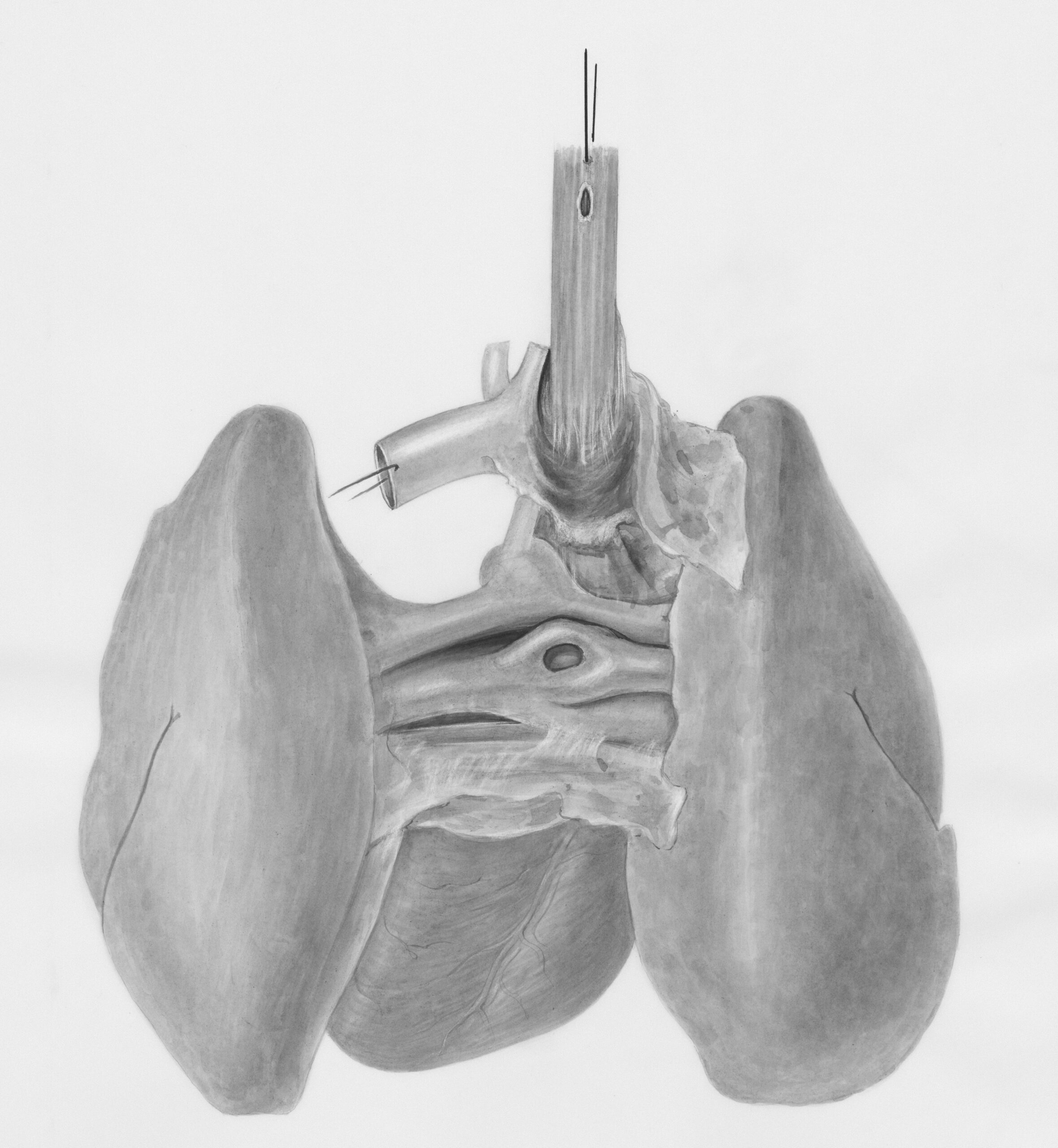

His flesh, they reminded him, was the solution to an intractable problem of modern conflict: the minds most suited for war don’t always occupy the bodies best equipped to fight it. A challenge that armies once resolved through beatings and discipline and the tedious work of indoctrination now streamlined, courtesy of a few defense contractor innovations, to some software and a simple procedure.

His parents liked to point out it could’ve been worse. Better to have his body drafted than his mind, because when they both get turned to pulp in a drone strike, only one gets replaced. The conscripted flesh keeps the loaner, but the conscripted mind — they don’t come home at all.

Cal consoled himself with that. Trying not to study the skeletal fingers wrapped around his steering wheel, or the sliver of a pale face hovering in his rearview.

Not his face, he told himself. Just a temporary replacement. A loaner. But that didn’t stop the symptoms from setting in.

It happened when he locked eyes with the stranger in the mirror. For a moment, he was still Cal. Then something in him broke, something he’d never known until he felt its absence. He reached inside, desperately trying to claw back this thing he couldn’t name — if he was religious, he might call it a soul — but it was already gone.

The ghost didn’t recognize the machine. So it had rejected it, like a failed transplant.

Numbness swept through him. A chill seeped into his bones, devouring everything, leaving behind only a vague and confused memory of the person he was before, a passenger in a vessel that wasn’t his own.

Derealization. That was the clinical term for it. A common post-transfer condition, in which emotion and identity disintegrate into abstract concepts, and the psyche unravels to deprive the external world of whatever gives it meaning. A brutal, efficient, and unstoppable defense mechanism.

When the first wave broke, Cal found himself kneeling on a dusty roadside, his throat raw from vomiting.

He forced himself not to cry, not knowing this would be the last time he could.

###

Cal didn’t plan on returning to the bar. Even promised Venditti he wouldn’t. But another night at the shelter seemed like hell, and snow was starting to fall, and there was nowhere else to be.

For three hours, he keeps watch, scanning every face that passes through the door. Occasionally, he’ll stop somebody, show them pictures of his old flesh, and ask if they’ve seen it. Most ignore him. A kind few take a glance before shaking their heads and offering half-hearted apologies.

He imagines Bobbin sitting beside him, cracking jokes to take his mind off things. Like he used to when they shared a room, every night before, he got high and trailed off into whispered dreams of revolution. Dreams that Cal never took seriously, until it was too late.

The place empties out around two. There’s no sign of his ghost.

The owner eventually asks him to leave, in that patronizing voice people always use with the conscripted. Sympathy for loaners didn’t last long after the war began. The best anybody can do now is pretend.

Cal blinks back and asks for a drink. The owner instead reaches up and taps a poster mounted behind the bar, striped glossy red, white, and blue with the Selective Service emblem centered:

CONSUMPTION OF ALCOHOLIC BEVERAGES IS PROHIBITED FOR GOVERNMENT-ISSUED ORGANICS, U.S. Code § 3809.

THANK YOU FOR YOUR CONTRIBUTION.

“You know they don’t enforce that,” Cal says.

The owner doesn’t answer. Painfully sober, he staggers back out into the cold.

###

Two months after the procedure, his parents changed the locks on him.

Their apology text unspooled over several paragraphs. His mom said she couldn’t take it anymore, watching whatever was left of her son wither away inside an artificial shell, reduced to one of those shambling corpses she saw on the news. His dad just wanted him to find a job. He had his degree, after all, and shouldn’t that have been enough?

They didn’t understand that nobody wanted to acknowledge the loaners existed, let alone offer them work. He was a hideous, soul-sucking reminder of the war only the politicians wanted, and of the sons and the brothers and the friends they’d surrendered to it.

He sat on his front porch and called them, getting the voicemail every time. Struggling to articulate his symptoms, so many abstract experiences that were no less debilitating for his inability to put them into words, because clinical language didn’t exist to describe them.

After an hour, the answering machine filled up. He tried to text, but they’d blocked his number.

###

It’s three in the morning, but light still filters through the grimed-up windows of the loaner’s shelter.

Inside, Cal finds Deion strapped into the tattoo chair, and Venditti working the needle. The extra seats from the support group are piled in a corner with their virtual therapy deck propped against one of the legs.

Without looking up, Venditti shifts his posture to one of accusation. “Where were you?”

It’s a threat, not a question. The shelter has limited beds, and Venditti doesn’t squander them on people who chase ghosts, who break their promises, who won’t do the hard work of healing.

“Taking a walk,” Cal answers. Then, changing the subject: “What’s the tattoo?”

The needle lifts to reveal a work in progress. Flowering vines, not yet shaded, entwine a dagger underscored with a date in Roman numerals.

“It’s for Bobbin. Everybody’s getting them. You want next?”

The blood trickling down Deion’s shoulder makes Cal grimace. As much as he likes the look of tattoos, he’s scared of needles and the idea of permanence.

But tonight, he’ll bear it. A little group bonding might buy him some forgiveness.

Besides, it’s for Bobbin.

Cal slumps into the chair once Deion shuffles off to bed, deep in derealization. He lets his mind wander as the needle bites up and down his bicep. Replaying that scene over and over, from the first glimpse across the pool table up until the moment he lost his face in the crowd.

His face. It’s been how long — six months? — and already, his memory of it has started to fade. He strains to picture its curves and contours without reaching for his phone. What did it even look like?

An impression of movement draws his attention to a high window, looking out onto the street.

Like that.

He sits up.

Venditti shouts and pulls away the needle, but Cal doesn’t hear him over his own pulse hammering in his ears. It was barely a flicker, a shadow, but he saw it.

A firm hand pushes Cal into the chair. “Relax. It’s not real.”

“Let me go,” he breathes.

“It’s the symptoms.” Venditti holds him down, maneuvering the needle back over his shoulder. “I know they’ve been worse for you since Bobbin died. Just let me talk you through it.”

Cal glances at the half-finished design, the wispy outline of a blade encircled by vines, thorns traced but no flowers yet. And now he can’t help but imagine how that knife felt in Bobbin’s hands as it came down — if he hesitated, wondering if his real body was out there somewhere…

“I get it,” Venditti says. “You two were close. But it’s not your fault what he did.”

More images from the demonstration flash through his mind, unbidden. The glint of sunlight on metal. The close-up of Bobbin’s face. The waters of the reflecting pool tinged rusty orange with artificial blood. “Don’t talk about him like that,” he whispers.

“He abandoned you, Cal. He abandoned all of us.” Venditti’s grip tightens. “And do you know why? Because he gave into what you’re fighting now. He never moved on, and it destroyed him.”

“So you’re afraid I’m going to wind up like he did?”

Venditti’s lips press into a thin line. “I’m afraid we all will.”

Cal snaps his gaze back to the window, determined. Bobbin’s dead. But this — this is real. This is all that matters.

“Your flesh is gone,” Venditti growls. “You understand? Probably not even pieces left. Not even bones. Just ashes and dust, scattered across a thousand miles of empty desert. You can either accept that and live in this body, or you will die every day searching for something you will never, ever find—”

He seizes Venditti’s wrist and twists free, with more strength than he knew his loaner was capable of. Blood and ink drip down his arm as he starts toward the exit.

“You want to chase ghosts? Fine,” Venditti shouts after him. “But you forfeit your bed.”

Running now, Cal throws open the door, peering out into the street. There, through the gusting snow, he can still distinguish a shadowed figure hurrying along the sidewalk. A figure that might have passed by moments before, wearing his face.

“You hear me? If you leave, you don’t come back.”

Cal is gone before he can finish the threat.

###

His parents only contacted him once after he found the shelter.

He and Bobbin were getting high in their room, smoke swirling beneath their cheap LEDs, when his phone flashed a message from an unknown profile. No name attached, but the style instantly reminded Cal of his dad.

It was an apology for kicking him out. And an invitation to come home, as soon as he had his own flesh back.

Cal had never looked into the rate of restoration statistics. Venditti discouraged it, said obsessing over percentages and probabilities distracted from the real goal of therapy, which was acceptance, living in peace with the body you have. But he knew Bobbin followed the unofficial data, keeping tabs on the leaks that circulated on loaner message boards. The closest they had to real estimates. So he asked.

A long trail of smoke rose from Bobbin’s nostrils. His eyes, frosted over with a psychedelic haze, wandered across the revolutionary posters tacked to his half of the ceiling. “Last I’ve seen, it’s two percent,” he mused.

And, laughing, he added, “How do you like those odds?”

###

Ghosts dance in the snowdrifts. Phantoms of form and flesh coalesced at the edge of Cal’s vision, creating an illusion of sidewalks lined with infinite copies of himself — his real self — running one into the other, if only he’d turn to look at them.

Derealization rolls over him like a thick fog. It takes all of Cal’s strength to stave it off. To keep his legs moving, and his focus on the smudge of a figure far ahead.

Snow piles up around his ankles. Wet, heavy flakes fall in plumes that scatter the sickly green glow of the solar lanterns, rendering everything more than a block ahead a mess of swirling static. Each breath burns in his lungs, but Cal barely registers the pain. He realizes, too late, that he forgot his jacket, and recalls all the stories he’s heard about loaners who froze to death in the streets because they never felt the cold.

The figure turns a corner up ahead. Cal shouts after it, not sure if he has a voice to shout with.

He collapses at the intersection, searching the distance and finding nothing but the flicker of far-off traffic lights.

Maybe he can still go back, he thinks. Maybe Venditti will forgive him.

But what’s waiting for him there? More empty therapy sessions, filled with broken men reaching for words they don’t have to describe feelings they don’t understand? A lifetime trapped in a body that will never be his, hostage to a mind that will never accept him as himself?

He staggers to his feet, which are already numb from the snow, and forces himself ahead against the wind.

Derealization swells. The already abandoned streets become otherworldly, dreamlike. His vision flattens, sounds go dull and distant, while the ghosts whirl all around him, creeping closer… closer… closer…

One of them stands still, apart from the masses.

Cal gives in. He turns toward it.

And after all the others evaporate, that one ghost remains. It stands alone on the sidewalk, its breath rising in clouds of vapor. A sliver of a face — a face that almost looks like Cal’s — pokes out from beneath its hood.

Before his vague sense of recognition can condense into certainty, the ghost turns and ducks into a metro station.

In another second, Cal is bounding down the steps after it, cursing his loaner and its slow, useless legs. He chases the ghost as it sprints down the length of an arriving train. It slips into the very last car, and they lock eyes through the window as the speakers chime and the doors start to close—

Cal lunges, outstretched fingertips sliding between the doors. They bounce open just long enough for him to tumble into the empty car.

Empty, except for one other person. Himself.

The doors snap closed, and the train eases forward. The person wearing his flesh gives an awkward smile.

“Do you want to talk?”

###

The soldier tells Cal everything but his real name.

They called him up in ‘34, fresh out of high school. He wasn’t patriotic or combat-trained or suicidal like the other conscripted minds, but the algorithms must’ve spotted some potential in him, some deviation in his test scores or a particular skill that made him useful for war. So they spliced him into the new flesh and sent him off.

That first body didn’t last him long — it got shredded by a walking turret two weeks in. Combat took three more, with him narrowly escaping brain death each time. Cal’s flesh was his fifth.

As he finishes his story, the tunnels outside peel back to reveal a distant skyline, still wreathed in early morning mist. They’re deep into the outskirts now. Cal’s lost count of the stops.

“So what are you doing back stateside?” he asks. “They send you on leave?”

A grin creeps across the soldier’s borrowed face. It’s changed since it belonged to Cal, or maybe just grown older. The hair is cropped short. The skin is weathered. There are scars in places he never had them, souvenirs from battles he never fought. “They didn’t give me permission, if that’s what you’re asking.”

Desertion, then. That’ll complicate things. “You weren’t afraid of getting caught?”

“Don’t think I’m afraid of anything now.” The soldier shrugs. “All those deaths, they add up. Not everything survives the transfer. By the third or fourth time, it’s like waking up dead, because most of you already is, and you’re just waiting for your heart to stop.”

“So you ran away.”

“You could say that. But if I was going to die fighting, I’d rather fight the people who did this to me.”

“Our people, you mean.”

He nods. “I hitched a ride home and joined one of the anti-war groups. Bunch of conscripted minds with nothing to fear and loaners with nothing to lose. Thought we could do some good.” A breath whistles between his teeth. “We organized a demonstration and, well, things went too far.”

“Which one?”

Anxious eyes dart to Cal’s incomplete tattoo, still leaking ink and blood. “You remember the Mall?”

The Mall. Cal’s stomach twists at the mention of it. He remembers jostling for a spot in front of the shelter’s television when they first aired the footage. Confused at first, unsure what he was watching. Just a handful of loaners loitering in the shadows of old monuments — and Bobbin, to his shock and horror, standing among them.

It all happened so fast, in a blur of skin and steel. The loaners dropping their coats into the reflecting pool, baring knives and pale, naked bodies, and the tourists screaming as their blades turned inward and those bodies fell — then the jarring cut to the close-up of Bobbin’s face, the one etched into his nightmares —

“That was you?” Cal says.

The soldier’s silence is answer enough. Cal sinks back into his seat. “So that’s what this is. You deserted, made too much noise, and now you’re trying to ditch your body.”

“Is that what you think?”

“Nobody gives up real skin for a loaner.”

“True, but I didn’t have to come all this way. I could’ve swapped with anybody.” The soldier pulls out his phone, shows Cal the screen. “You should thank your friend. He’s the one who sent me.”

Cal studies the photo. It shows a loaner, standing with one arm looped around the soldier’s neck. A loaner with unmistakable tattoos and a smile that once split the darkness of their shared room.

Inklings of forgotten emotions flicker at the corners of Cal’s brain, only to drown in a wave of derealization he can no longer hold back. “Bobbin,” he whispers.

“That’s the one. He recognized your flesh from the pictures you showed him. Made me promise to return it.”

Cal sits motionless for a while, staring so hard at Bobbin’s face that it slides out of focus, and regretting all those bitter, angry months when he thought his friend abandoned him. “Why’d you take so long?”

“Wanted to make sure I had the right guy.” The soldier laughs, and a part of Cal twists at the sound of it. The ghost longing for the machine. “Almost gave up on you, too. I visited your shelter, but the guy running the place kept sending me away. Thought I was delusional. He said that you needed to heal, to move on, and I would just get in the way.”

“But you ran from me.”

“Because I’ve heard enough stories about loaners snapping on people they mistake for wearing their skin,” the soldier says. “I wanted us to meet in a controlled environment. So much for that.”

The train lurches and groans to another stop. Snow gusts through the open doors, swirling beneath harsh fluorescents. “So how do we do this?” Cal asks.

“I know a cut-woman who runs her own clinic,” the soldier says. “She does the procedure on demand. Just name the day and time.”

“How about now?”

He raises his eyebrows. “Does it have to be?”

Cal shoots him a glare that makes his position clear: either Cal leaves with his body, or neither of them will.

The train doors shudder closed, and the soldier’s gaze flits to the metro map. Their location blinks near where one of the lines runs off-screen. “We’ll be there in two more stops,” he says.

###

Police lights strobe over the snow-dusted sidewalks outside the loaner’s shelter.

Memories of that building and the stranger who lived there swirl through Cal’s mind, but they don’t feel like his own. They’re more like the fleeting afterimages of a dream, and he wonders if they’ll fade just the same — if he’ll forget Venditti and Bobbin and all the rest, leaving nothing but lost months in their place.

Maybe that’s why he came back. To assure himself it was real. To say goodbye to the stranger, in his own skin.

He also wanted to say thank you, but it doesn’t look like he’ll get the chance.

Cal’s heart drops into his stomach as the police march them out, one by one, into the bright and bitter morning. Half a dozen loaners, stumbling shirtless with their hands cuffed and their illegal tattoos on full display for the news cameras.

One of the officers stands apart from the crowd. Cal takes a spot beside him. “What happened here?”

“Huge bust.” The officer leans against his cruiser, gesturing with a cigarette pinched between his fingertips. “Bunch of conscripts caught damaging their loaners.”

“But I thought this was a shelter for them?”

The question earns Cal a side-eye glance and a shrug. So? the cop seems to say.

He grits his teeth. “Since when is it illegal to damage a loaner?”

“Always has been. That’s the law.”

“I know, but when did you start enforcing it?”

The cop thinks for a moment, tapping his cigarette. “Between you and me, the order came down yesterday. Supplies are short for the next round of call-ups, so they want us repossessing as much as we can.”

The taste of bile rises in Cal’s throat. So that’s all this is. More war meat to fuel the machine.

A cold wind picks up, sending sparks of pain needling down the back of his neck. He winces as he adjusts his scarf. His fingers graze the half-hidden seam of ragged flesh, and they come away stained red.

The cut-woman kept the procedure clean, but there’s only so much you can do in a back-alley clinic. When it was over, rivulets of fresh blood trickled through grates in the operating room floor, a steady drip, drip, drip that beat at the edge of Cal’s returning consciousness.

Cal’s blood or the loaner’s, he wasn’t sure. All of it ran together.

His rebirth wasn’t immediate. It took an hour, maybe two, maybe three, before something stirred in the profound silence of his derealization, and he could truly identify himself as the figure in the mirror, with its lips slowly twitching into a smile.

Now, as he trembles at the sight of a final loaner stumbling through the snow, it’s impossible to remember how he ever felt so numb.

“That’s the guy who ran the place,” the officer scoffs. “Turns out he was encouraging them, too. Said it was part of their therapy. You believe that?”

His words don’t reach Cal. For an instant, he meets Venditti’s gaze across the street, searching in vain for some sign of recognition before his old friend vanishes behind the tinted windows.

The next question lingers on his tongue: what’ll happen to them? But the answer’s already there, in the fine print on the posters and the billboards and in the virtual therapist’s warnings. What was given would be taken away.

Anger surges in Cal, as powerful as it was when he first watched them cart away his flesh. It’s good to feel something that strongly again. Even if it’s painful. Even if it’s useless.

Or maybe, this time, it doesn’t have to be.

The police van rumbles away down the street. The cop turns to offer Cal a smoke, but he’s no longer there.

###

His ’27 Dodge waits for him two blocks away. A loaner reclining in the passenger seat sits up as he approaches, massaging the back of his neck.

The soldier takes his feet off the dash as Cal slams the driver’s side door. “Everything go alright?”

“Sure,” Cal answers. It takes a few attempts to get the car going, the motor coughing and whining before thrumming to life. “Listen, I was wondering — what if I didn’t drop you off at the station?”

“After all that, you’re gonna make me walk?”

Cal shakes his head. “No, I mean, I could go with you.”

The soldier regards him curiously, through eyes that seem too focused, too keen for someone with six bodies’ worth of derealization. Eyes that had once been Cal’s were now trying to peer back into his mind. “You’re serious?”

“What else is there for me to do?”

“Go home. You have your body, now get your life back. That was the plan, wasn’t it?”

Warm, gasoline-tinged air blows from the vents, stirring the papers strewn across his back seat. Templates for forged documentation, with columns of personal information left blank. Necessary protection for somebody wearing a deserter’s skin.

The sight of them makes Cal smile. A new name feels fitting for his rebirth. “The plan changed,” he says. “There’s nothing left for me back there.”

A sigh escapes the soldier’s lips, long and low, and he lolls his head back like he’s thinking about it. Somehow, Cal already knows his answer. He figures it’s just intuition, but doesn’t rule out a deeper bond, some wires that got tangled between them in the transfer.

“It’s a losing cause, man,” the soldier says at last. “Don’t say I didn’t warn you.”

In the grand sense, Cal knows he’s right. Alone they won’t topple the war effort. But from what he understands, the soldier’s movement has numbers and a network. Enough to help a few more conscripted minds escape the draft, and to reconnect a few more loaners with their lost bodies. And to resist, in whatever small way he can — that’s good enough for him.

It took going to derealization and back to understand that. What Venditti and Bobbin both tried to prove in their own selfish ways.

They can steal the body, break the mind, strip away identity and the ability to feel — all else gone, some spark of humanity endures. And that spark will bend toward defiance, raging to reclaim the memory, tarnished and faded, of what it’s lost, of what it might be again.

Until they develop a procedure to take that, they won’t win in any way that matters.

“Maybe,” Cal says. “But it’s better for us to go out fighting, right?”

“I didn’t realize there was an us,” the soldier scoffs.

The Dodge’s whole frame shudders as Cal shifts it into gear. “There is now.”

It’s a quiet ride into the outskirts. The soldier sleeps off the leftover anesthesia while Cal drives in silence, thinking about Venditti, about Bobbin, about his parents, about the two lives behind him, and the one that lies ahead.

As he speeds past the city limits, heading toward a different horizon than the one he came from, the first tears start to fall.

Cal doesn’t know who they’re for. But this time, he doesn’t stop himself.