The Cost

Your mother refuses to mention the costs associated with this trip. It is your 16th birthday and the first you’ve celebrated with more than a cake and the same, flickering e-candle. She greets every new experience like a test of will and haggles with the taxi driver to get to the spaceport. He promises a discount if you book him for the drive back home. Despite her insistence that yes, this is a wonderful birthday wish, you listen to her force a lighthearted laugh through the mountain of additional fees once you arrive at the kiosk. Choosing to be seated together incurs a fee, as does the inclusion of recently upgraded turbulence-reducing hydraulic backrests. From your mother’s clipped tone rushing you through security, you can tell the price is not what she expected.

The Baggage

There is no carry-on baggage allowed on the Aegis Starliner, for the spaceport of departure is also the destination. Personal photography and recording devices are not allowed on the flight. Not only do pictures taken from the cabin fail to capture the view, but personal electronic devices have become increasingly used on Starliner flights in small bouts of eco-terrorism, at times disrupting communications between the pilots and air traffic control. Such is the reasoning provided to you and your mother as her phone, wedged between waistband and skin, is discovered and confiscated. The Aegis has its own high-tech camera system embedded in the tailfin, a security officer assures you, and video recording of the flight will be available upon landing at a small fee. Small fee, your mother mutters. In line to board the plane, she flirts with a man clearly dressed for first class. She peppers him with pleasantries, and he counters with a joke about her age. Your daughter? He shakes his head. Surely you mean your sister. Your mother wraps an arm around you. She keeps me young. You dig your elbow into her ribs. Gross, Mom. She tightens her arm around you. Gross me? Coming from Miss “clogged the drains again this morning?” The man chuckles. You ladies have a nice flight. At your seats by the lavatories in the back of the cabin, your mother primps her hair. She is beautiful, with hazel eyes and thick brows lined by years of concentration, but the man doesn’t look back. Regardless, her mood has shifted. Maybe a flight video could be nice, even for a fee… it’s not every day…

The Route

Still grounded, as the crew makes its final safety checks, a flight attendant explains that it is a special someone’s birthday. Your chest soars and your cheeks flush, but as you look at your mother, her smile has turned lopsided. She squeezes your knee and gives it a shake. A member of our Frequent Flyer Program, the flight attendant continues, has ordered the Sagittarius Special to mark their special day! Would everyone join me in wishing Jackie a happy birthday? You join the cabin in singing Jackie “Happy Birthday,” but in the third line, your mother replaces Jackie’s name with your own and gives you an awkward hug over the armrest. This is better, you think. You wouldn’t want all that attention on you. The Sagittarius Special, the flight attendant explains, starts and ends by breaking through the troposphere and into the exosphere underneath this special constellation. Everything seems to be special for this flight attendant. Her hair is smooth and long and so blonde it looks white.

The Tech

Once the cabin is pressurized and the air begins to hiss, everyone takes off their masks. The hermetically sealed hull is pumped full of clean, pollution-free air, and your skin tingles as if you just shaved. Normally, you wear a mask outside and in public spaces, but last week, the dry, flaky sealant around your apartment windows finally cracked, and your mother insisted you both wear masks at home, with the exception of showers and mealtime. Showers were already short to save water, but now meals have been rushed too, and it’s freeing to peel the stuffy mask off. You and your mother smile at each other. She blows gently at you, kissing your cheeks with clean air. No smog, she says, no landfill smell. After explaining the air pumps, sealants, Mach-two engines, emergency exits, seatbelts that would you please clip in like so, the stewardess gestures to the ceiling. The hull is made of carbon-fiber-reinforced polymer and offers a cabin with entirely see-through walls. The bottom has been painted over to prevent vertigo, but the roof is the Aegis Starliner’s raison d’être. Above, you see the grey haze of sky you’ve known for as long as you can remember. Up front, above the cockpit, the sun is a watercolor hint of orange. Once you reach the outer atmosphere, you’ll see the real sun, which your mother assures you is round like a basketball, the moon (she tells you to look at how hole-y it will seem), and the stars. Like tiny polka-dots. You’ve read about them granting wishes, and while you’re not silly with hope like some of the other girls at school, you wonder if star wishes and birthday wishes might add up to something more.

The Passengers

A few rows up, a girl complains about her seat, about how the exit row sign is going to block her view. You hear the stewardess apologize and explain that the inconvenience of the sign is the reason for the girl’s additional legroom. However, the stewardess continues, they can see if there are any options available to switch the girl around. Is there anything at the front? The girl reminds you of the friend at school who suggested you try a trip on the Aegis Starliner – the same friend who vacationed on Mars and groaned about how the mountains of safety gear took out all the fun. As the pilot and crew make their final checks and passengers strap into their seats, couples kiss, a child clutches their father’s hands, and the stewardess stops by one last time to see if anyone needs anything. Your mother flags her down. How many of the flights have you been on? She has strapped her seatbelt as tight as it will go, cutting into the soft mound of her belly. Hundreds. After takeoff, it’s a smooth flight. You lean over your mother to the stewardess. How’d you get this job? The stewardess bends over as if to share the secrets of the universe. Everybody here knows someone who got them the gig except maybe the co-pilot, who was in the Air Force and a doctor. So, you know. Do as many favors for as many people as possible, and somebody might owe you something. Your mother draws herself tighter against the backrest, pulling in the new centimeter of seatbelt slack. I wanted to be a doctor, but blood just wasn’t my thing. The library desk was much more my speed. But did you hear that? She turns to you. Hard work can get you anywhere. Even here.

The Turbulence

Takeoff proceeds, and the plane begins to rumble and roar. The acceleration pushes you back into your seat, and every few seconds, the plane seems to twitch left or right down the runway, as if it is only mostly sure of its path forward and into the air. You watch the rows ahead of you begin to lift until your blood is pushed down into your feet, and the ground, which you never noticed as quite so constant before, no longer pushes against you with its natural resistance. The earth below you has shifted from a fact to more of a feeling, a hope. Your mother grips your arm and cycles through a pack of gum in five minutes, and every so often, your stomach flips as the plane shakes. At high enough speeds, the air is more the consistency of Jell-O, according to your friend. You know the plane is safe, low risk, suspended in gelatinous high-speed oxygen, but the plane doesn’t seem to know this. Every few minutes, it bucks, taking a dip that flutters your heart or rising so fast that you feel twice your weight. So smooth, a couple whispers in the row ahead of you. The hydraulic turbulence-stabilizing seats were really worth it. You don’t notice that you’ve furrowed your eyes closed until you open them, your mother grimacing back at you. She looks a shade of yellow that you’ve only seen on the man who seems to live in the bus that takes you to school, always sleeping and cradling a bottle in a paper bag. Look, your mother says. Outside, the plane has breached the last layer of grey smog clouds.

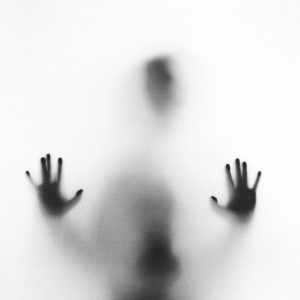

The View

The first thing that strikes you is the Sun. Already half swallowed by the Earth, it blinds you momentarily. The brightness has no color, not yellow like you were told, or rust as it appears on the surface, but a kind of all-encompassing white hole in the sky, as if burned from your memory the moment you see it. An overabundance, an absence. When you blink, the white crest cuts through the black of your lids. It’s easier to look at the colors it casts on the buttermilk sky. Pinks and purples ripple through the crevices in cottage cheese clouds, floating on an ocean of spilled orange juice. Above, the air hardens from pale to chromatic blue, as if the Earth is coating itself in a shell. The Moon, pimpled and cracked, shines with far less brightness than the Sun, a welcome refuge. Look at me. Small green patches like mold spots point to the lunar colonies: luxury, penal, industrial. Then the Sun goes to rest behind the Earth’s horizon, pulling its blanket of colors with it, and for a moment, you are disappointed. The spectacle ended so quickly, and now you are left with the dark and a cold, blank sky. You rest your head against the cool cabin wall. It was so pretty, you can imagine telling your friends back at school, but it was over so fast. Don’t bother... A gasp from a few rows up snaps you back. Murmurs ripple across the seats, and your mother points straight up. It takes you a second as the glassy black above seems to texture until you see a point of white and another, and suddenly the sky blushes, and space itself is dotted with pricks of white and blue and what looks like clouds of faint brown light. Like a sneeze suspended in the air. Whenever you look at a Star, a thousand others tease the edge of your eyes. In every corner of the sky, there is another; some dance in shapes, others with color, and so many lights a gash across the inky black. At this time, the stewardess stands and begins pointing to constellations. You half pay attention to what she says. Sagittarius… a centaur with a bow… Cheiron, teacher of Achilles… The fastest and wisest of the centaurs, exiled to live on Mount Pelion away and above the world. It’s no surprise people thought the Stars were gods and beasts and that people who died wanted to join them in the sky. It wouldn’t be so bad to end up in their company. And it hits you, in a moment, that the Sun, blinding and huge from far enough away, is just another one of these twinkling dots, another freckle on cosmic skin. Your mother whispers excitedly, echoing the stewardess. The sun was passing through that constellation when you were born. Or, I guess at least, it used to. That’s what makes the constellation yours. Isn’t it beautiful? But you know the constellation is not yours. At any of those Stars might be a planet where the people look up and see this same sky every night, who don’t have to beg for their birthday, who don’t have to rocket off their planet to access the millions of lights and colors in the sky. You choke on the jealousy like the polluted air of the surface, heavy, bitter, hard to breathe. And it occurs to you that your mother watched from the surface as a child while the last of the Stars dwindled into a haze. Until now, you had never known the Stars, and yet your mother had known them and lost them. You want to pluck them from the sky and give them to her. Light drizzles down your mother’s face, caught in tearstreams on her cheeks. You notice your face is wet too and cold, minted in the clear air. And on your lips, the taste of salt.

The Landing

When you re-enter the smog, the turbulence isn’t nearly as jarring as the weight of the clouds around you. The grey closes on the sky slowly, then all at once, like a door slamming shut. Deplaning, you and your mother thank the stewardess at the front. Our pleasure! I hope you enjoyed the trip, and we hope to see you again! The people getting off the plane look entirely different than those that boarded with you. You’re certain that the woman in the seat in front of you is blonde, but as she waits for her turn to exit the plane, her hair looks dull, flat, brown. Your mother keeps recounting the names of the Stars. That one exploded when Grandpa was a kid. That’s why the constellation was a different shape. How could the Stars be anything other than immortal? Will you ever see them again, to compare? Will your mother? The mask on your face is already feeling stuffy. The outside air at the spaceport exit has never felt so dense and hot. You point to the spot where you had been dropped off, where the driver had promised to wait. Taxi guy ditched us. Your mother doesn’t seem to notice – or doesn’t mind. She waves down the nearest cab and haggles through the cracked window.