Twigs snap under my boots like thin, frozen bones. Behind me, the wind is hurrying the fog across the darkness. I glance one last time over my shoulder, back to the village—its warm orange glow, barely visible at this distance—back to the house where my family prays pointlessly over my soul. Then I turn and hurry further into the forest. Deeper into its ragged embrace.

I was barely granted a warning. Barely enough time to gather my clothes—mindlessly reaching for my warmest cloak, as though extra wool would be enough to keep out the chill of the numberless days that now lie before me. Barely enough time to slip out the back door of my home, less than an hour before the minister is due to arrive in town. Tomorrow morning, the trials will begin.

I was barely granted a warning, yes—but I should not begrudge that warning. God gives no such warnings. Just ask Goodwife Sarah, whose faith did not save her. Whose husband—a man who still holds a high seat in the church, still smiles down at the mass-goers each Sabbath—struck her too many times and too strongly until he had put her down at last, placed her below his feet forever in a rocky grave. I can see her hair, once blonde as summer wheat, slowly turning white in the airless dark. God gives no warnings: just ask the saints, those few and venerated, plucked from the masses of those suffering and given titles that will never expire. Just ask all those other millions, whose faith was no weaker, whose suffering no less honorable, but whose names are now as ancient and distant as the stars.

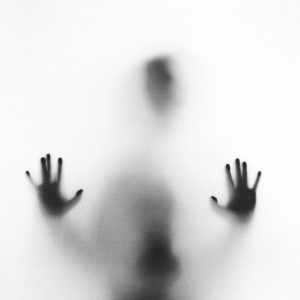

I am deep in the forest by now. The light and noises coming from the village have faded entirely, leaving only the snaps of the twigs, and the crunch of my feet on the dried leaves, and the brush of my cloak across the ground. The cold seeps under my collar, seeking to freeze my bones until my limbs are as stiff as the arms of trees stretching black above me—this latticework of branches against the endless evening sky. The rising moon is my only source of light now, gleaming narrowly through the trees. I must use my hands to help guide my way, tearing the skin on rough tree-bark as I pick my way deeper and deeper into the forest.

But then I think of the power that brought me here, that gave me the warning to flee and the skill to hide. Warmth glows inside me, flares in my body, almost carves my chest open. If the smiling wife-killer on the pulpit were to see me now, he would tell the congregation that I am damned. That my soul is a dark dead thing. But it is of no matter: I will survive. I will survive long after all the other accused—girls who would not know witchcraft if they lived a thousand lifetimes, who assume it is all brimstone and devils and runes—are hanging lifeless from trees.

My feet are numb with cold by the time I reach the clearing. Here the trees pull back, as if in awe, allowing the moonlight to bleed down fully onto the grass. In the middle of the clearing is a mound of earth, as long as a man and half as tall as one. I fall to my knees before it. I reach out and—yes, yes—it is not hard. The ground around it is cold, but this mound, its dirt, is the same temperature as my body. I scoop parts of it away, my hands gleaming pale in the moonlight. Lunar ghostly things. Soon I, too, will be something like a ghost.

Once I’ve cleared enough dirt to make a space for myself, I burrow into the mound, lying on my side. The dirt settles softly around my body and cradles my head. Then I reach out for what I’ve displaced and pull it back into the mound, walling myself in, shutting out the moon and the trees and the stars. I clog the hole with dirt until I am completely shut off from the outside. Burying myself alive.

Then, with barely enough space between my lips and the packed earth to form the words, I recite the phrase Sarah taught me. She spoke it to me years ago, back when she was a blasphemer like me, an outcast, before she married the minister and became a good Christian woman. Not that it saved her in the end. Now she molders in the dirt and the dark but her words have survived, they live in the root of my tongue and the base of my spine and the hollows of my heart. I press my hands to my chest and speak the incantation that will bind my soul to the darkness for years and years hence—how many years, none can say, but long enough to be sure that the present danger will have passed—until I emerge reborn, renewed, into an age where I will no longer have to hide.

Secretly, I long for something else as well. Another Sarah. One who will let me count the freckles on her arms and chest and ankles until I lose track and have to start again. One who will let me tangle my hands in her soft blonde curls, wind our hands together until we lose track of whose fingers are whose. One who will not stand stiffly in her doorway, hair now hidden by her bonnet, a brand-new Bible in her hands—I half-expected it to burst into flames, but apparently God cannot be bothered with such theatrics in our modern world—and tell me that we were never to see each other again.

With this last wish on my lips, my eyes slip closed, and I fall into the sheltering dark.

At first, a pinprick of consciousness. A tiny glow. I am alive. My first thought in I don’t know how long. The sensation of emerging from a long dream.

I know immediately that it has worked. I have not been buried in here for a few panicked hours, no: my stomach is as full as if I have just eaten, although when I walked into the woods I was hungry and felt as empty as the skin of my cloak. I am warm; more than warm. The glow of life is white-hot within me.

I am alive.

I claw my way out of the earth.

And I see at once: the trees are gone. The forest is gone. The sky is gray and still and birdless. It is impossible to tell the season: the wind on my face is not the biting chill of winter, nor even of autumn, but the tint of the sky tells me it cannot be summer. All around me stretches nothing but bare dirt.

But in the distance, in the direction of my village, there is a long, low box. It is grayer than the sky, and hard-looking. Its corners are far too sharp. It looks like there are more of them behind it. Clustering, as though trying to remain out of sight.

Just structures, I tell myself. Nothing to fear. But these boxes—immense, they must be, seen from such a distance—fill me with dread. I don’t realize I’m crawling backwards until I hit the dirt of the mound.

How long has it been? How many years have I slept inside the earth?

I finally get to my feet. I’m steadier than I had anticipated—the words that kept my stomach and lungs full during my time in the mound have also kept my muscles strong. I don’t want to walk towards the sharp square buildings. But I don’t want to turn my back to them either. So I walk west, keeping them on my left, and presently I find myself at the edge of a wide gray road. It’s flat and even, and the material is rough—like no stone I have ever known—and cracked. Yellow stripes run down the middle of it, extending further than I can see, vanishing into the horizon.

Over and over again, as a child, I knelt and pressed my hands together and tried to speak to God. He never answered.

He kept on not answering until I no longer thought of him as god.

Other things, though—other things did answer, later, when Sarah helped me listen for them. The spirits of the air, the trees, the water. The firmament, blazing with stars. The earth, in whose breast I have now slept for untold years—perhaps decades, perhaps centuries.

So I walk a few steps back from the strange, rough road. I close my eyes and place my hands on the earth. I say the words Sarah taught me long ago—warm scent of her skin, lips reddened with late-summer strawberries; these memories have not faded—and ask how long I have been in the ground.

The earth doesn’t respond with words, but with images. I see my village again, but I don’t have the chance to scan for familiar faces in doorways, because everything is sped up ten times, a hundred times—people moving so fast their bodies turn to blurs against the houses. Soon I see the villages’ occupants leaving, a mass exodus, leaving the structures to molder and fall like rotting trees. Finally, everything is torn down and carted away and larger, more impressive structures are built. For a while their occupants run frenzied circles around them until they, too, disappear. The earth churns under the blades of strange machines, like the ones we use to cut our wheat but larger, so much larger. Their bright colors sear into my eyelids. The earth is torn up again and again, buildings replacing buildings replacing buildings, until the structures that are now present are erected: six levels tall, taller than any house I have seen in my life. Up close, they are massive, like new gods peering out over the barren earth.

Centuries, I think, the word like a bell tolling slow and heavy inside my chest. Many centuries. And my body grows brittle with dread. This world is alien to me, as strange as another language, slippery on my tongue.

But I am safe now. The earth would not have let me go until I was safe. I am safe, and maybe—maybe my last wish will come true as well.

Warmth carves itself in my chest again, like a beautiful wound. I get to my feet. I put the grave of my old village, and the heavy gray structures that hunch there now, to my back. I start walking north, along the edge of the road, following the bright yellow stripes that streak down its center. They are as vivid as Sarah’s hair when it caught the sun. As I walk, I remember her, and smile.