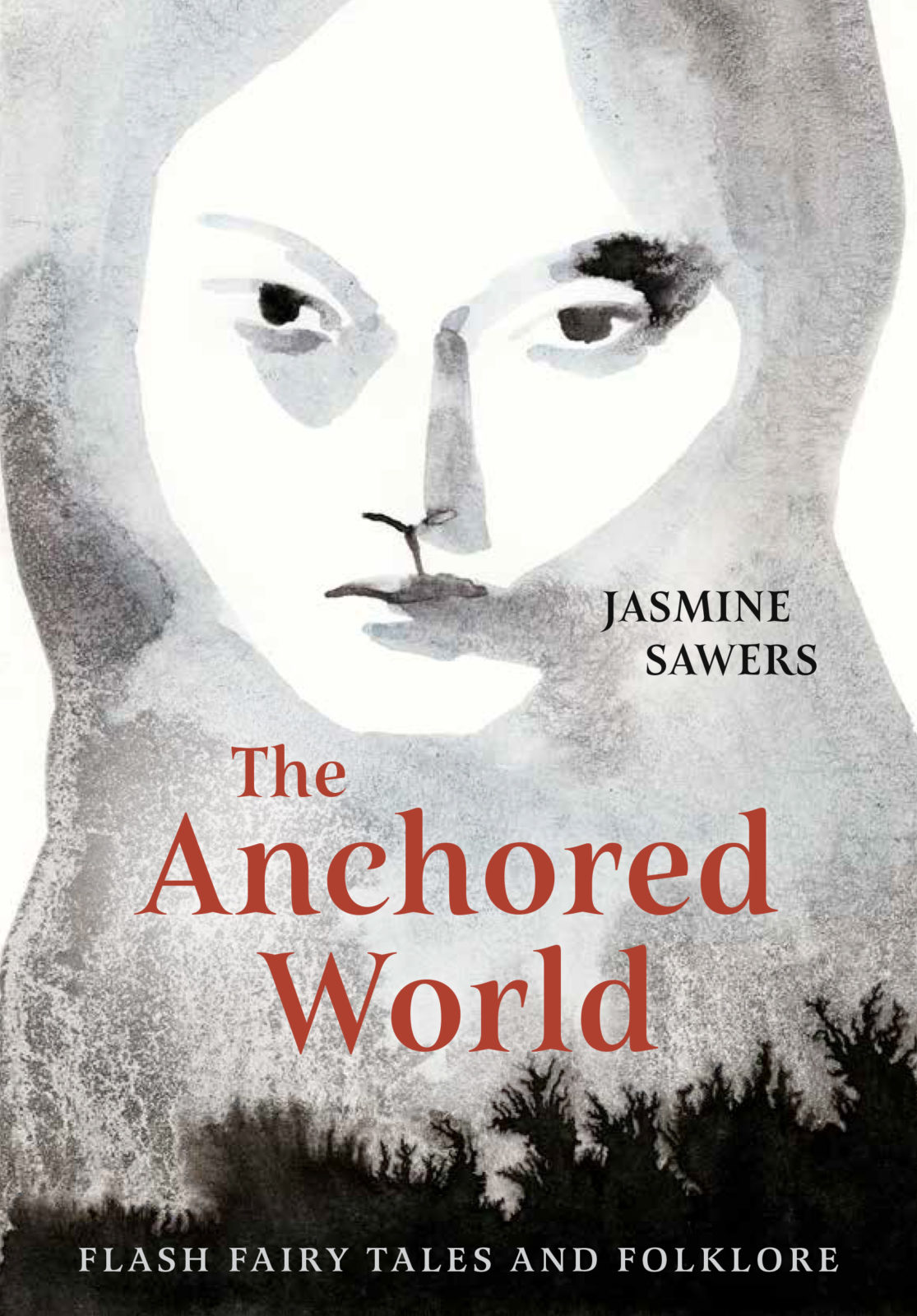

Jasmine Sawers is a writer, editor, and teacher. Sawers’s fairy tale flash collection, The Anchored World: Flash Fairy Tales and Folklore, was recently released by Rose Metal Press. From the publisher:

The Anchored World: Flash Fairy Tales and Folklore

“Drawing on both Western fairy tales and Thai legends, these flash fictions combine the myth and the modern, the realist and the fabulist to build the legend of the author’s own hybridity: Thai and white, Muslim and Catholic, Buddhist and atheist, second-generation immigrant and umpteenth-generation American, male, female, both and neither.”

Huge thanks to Jasmine for talking with me about The Anchored World, fairy tale writing, and trends in this exciting branch of speculative fiction.

—Myna Chang

***

MYNA CHANG: Your website says you received the Random House book of fairy tales in 1988, and you never got over it. Can you tell us why you’re drawn to these stories? What speaks to you? What other influences have contributed to your style?

JASMINE SAWERS: For me, this is the germ of falling in love with stories, of becoming a storyteller myself. These are the blueprints for every story that’s come after. I’m interested in the darkness that lurks at their edges, and how, despite so many of them being quite bloodthirsty, they are understood to be tales we tell children and expect them to understand—and they do!—even while we pretend childhood is a time of joy and innocence. They also betray the values (and shortcomings) of the cultures they come from: beauty is goodness, ugliness is moral turpitude; kindness and virtue will be rewarded while greed and selfishness will be punished; women/foreigners/those different from us are not to be trusted; queer happiness is impossible; consent: what is it? And so on. I think these stories, and folklore in general, are fertile fields for narrative catharsis—as writers, we can trade on the familiarity of their motifs while disrupting or subverting expectation.

MC: Do you find commonalities, or significant differences, between Western and Eastern tales? How do you synthesize all these wonderful elements?

JASMINE: Something I find interesting about fairy tales, folklore, and myth, in general, is the persistence of theme and motif across cultures and continents and even time. When I’m being sentimental, it reminds me that storytelling is something we all have in common, and so are so many of the emotions, conflicts, heroism and villainy we can find across so many of these ancient tales: heartbreak, jealousy, bravery, cunning, anger, narcissism, poverty vs wealth, justice or the lack thereof, even all those dark little bigotries lurking in all the cracks of our societies.

Take, for example, Cinderella. The version that appears most often in fairy tale books, the one on which the Disney movie is based, comes from France and was originally written by Charles Perrault. But the Brothers Grimm collected stories from across Germany, and theirs is called “Little Ash Girl.” The oldest Cinderella story recorded in Europe is called “La Gatta Cenerentola,” by Giambattista Basile in Italy in 1630. They’re all a little different.

All fairy tales, like the ancient epics, were originally told orally, and thus their details changed as they traveled, so I shouldn’t have been surprised when just last year I opened up Fascinating Folktales of Thailand, Thai fairy tales retold and translated into English by Thanapol Lamduan Chadchaidee, and the first story in it, “Pikhul Thong,” was a Cinderella story.

There are Cinderella stories from West Africa, Indigenous America, Egypt, and England. Some say Yeh-Shen, from China, is the world’s first Cinderella. And, despite our thoughts about its author or the chokehold it has on our culture today, I would be remiss not to mention that Harry Potter is, of course, a Cinderella story.

It makes sense to me that this should be such a common tale. How can we not all be compelled, filled with feeling, by the basic ingredients of Cinderella? A kind orphan child, unloved and mistreated by those who should care for her, finds her voice, finds her power, forges her own destiny. Some things, I think, are universal.

In this way, the stories belong to no one, so they can belong to everyone.

MC: Do you do any research to fuel your imagination?

JASMINE: If we can call reading a lot of fairy tales research, then yes. I had to scour the internet and bookstores in Thailand for Thai stories written in English. I chewed my way through My Mother She Killed Me, My Father He Ate Me and XO Orpheus, anthologies edited by Kate Bernheimer. I inhaled the little weirds in The Turnip Princess and Other Newly Discovered Fairy Tales, only recently unearthed but collected and recorded by Franz Xaver von Schönwerth in the 1850s.

I read, religiously, every literary magazine that publishes fairy tale type work. I sought out work by contemporary authors of color working in the same vein to discover tales I had never seen before.

I read about fairy tales: what they reveal about their cultures, storytelling, symbology, how they shape our understanding of narrative. I scrolled through the Aarne Thompson Uter Index which categorizes world folklore by what kind of story each one is.

It never felt much like research. It felt like I was a kid again, sinking into worlds full of magic.

MC: Has the pandemic had an effect on your writing in general? Has it impacted the production of your book?

JASMINE: In the last year or so of my MFA and the immediate time after I’d completed my degree, I had been focused on flash, and I’d been told in many ways large and small, explicitly and implicitly, that I shouldn’t be writing flash and that I owed myself, my career, a novel. I kept telling myself “you don’t get to write if you’re not writing a novel.” But surprise, self-flagellation is not a motivating strategy! All it meant, in the end, was that I wasn’t writing at all.

In the summer of 2019, I went to the Kundiman retreat. It was not only an opportunity to talk about craft, writing, and fiction with other writers for the first time in many years, it was also the first time I had ever felt free to speak about the challenges and realities of writing from an Asian American perspective, a mixed perspective, a Thai perspective, a queer of color perspective in a space where people would not dismiss those perspectives or the various bigotries that dog our heels in this industry. It was my fellow writers at Kundiman who convinced me that my voice mattered, that there was a place for it in the literary landscape, and that these things were true regardless of the form my writing took. Being in such a supportive space, which not all marginalized writers are lucky enough to access, allowed me to come back to writing with a renewed vigor and confidence. I even found that in these intervening years, I had become a different writer with a different perspective: more myself, less hiding. I was mixed. I was Thai. I was queer and fat and nonbinary. I’d grown up in a white space with a great deal of covert racism. I didn’t have to write as though I were apologizing for any of those things anymore.

And then the pandemic happened.

Kundiman meant that stories were bursting out of me for the first time in a long time. Rose Metal Press’s deadlines meant I had a vested interest in making many of those stories cohere into a collection. The pandemic meant I suddenly had literally nothing else to do other than get these out and polished. 2020 ended up being the most productive writing year of my life. I also published more than I’d ever published before. In 2021, I published even more.

Now we’re in 2022 and we don’t have any idea when the pandemic will end. My soulmate dog died over the holidays and I had a major health issue for the first half of this year, both of which have put the kibosh on writing. Meanwhile, I’ve finally hit on an idea for a novel I want to pursue. Pivoting away from flash will mean less publication this year and probably the next handful, but I’m going to Kundiman again in June, and who knows what it’ll shake loose for me this time?

MC: How did you hook up with Rose Metal Press?

JASMINE: When I was introduced to flash in 2012, the power of the condensed form struck a chord with me and I suddenly had this pile of stories that I knew could someday be a collection. Meanwhile, everywhere I turned around, I was told by professors and agents that no one would ever publish a flash collection, that it was a futile endeavor I was wasting my time and effort on. But that didn’t stop the stories from bursting out of me. I came across Shampoo Horns in a friend’s house, so I looked more closely at Rose Metal Press, and I remember very specifically tucking it into my memory: when I had a full collection of weird fairy tale flash, Rose Metal would be the only ones to take it.

Now, Rose Metal Press opens for submissions for only one month every two years, and they take very few manuscripts. Every time I checked in on them I would have miraculously missed a recent deadline. But in 2019, I’d gotten the kick in the ass I needed to start writing again, and I saw that Rose Metal would be opening for submissions again in 2020. Time to get to work, I told myself, and I did. And it paid it off.

MC: What do you see for the future of speculative fiction and fairy tale writing? Any trends or changes on the horizon? Anything you’d love to see more of?

JASMINE: I think we’re seeing, and will continue to see, an influx of marginalized authors in speculative fiction. Writers of color, queer and trans writers, disabled writers have been lighting this genre up, perhaps because there’s an estrangement with reality inherent to the marginalized experience that speaks to a necessary emotional truth we can bring to storytelling outside the realist mode. We have been othered and alienated; now we’re bringing that ripple of unease to a genre that has historically been occupied mostly by cis straight white male writers.

I’m especially eager to see how marginalized authors pivot sci-fi and high fantasy stories away from colonization and the imperialist gaze.

MC: I know you’re a fanfic reader. Do you read just for fun? Do you think reading/writing fanfic can provide value for the serious writer? How do you see fandom fitting into the speculative canon?

JASMINE: Yeah, I’m old enough to remember when one’s fanfic habits were something to hide and never admit to, but I’m also old enough not to care too much what people think of me anymore. Still, I’m fairly shy of exposing my professional life to my fandom life. It’s been interesting to watch the evolution of fanfic coming into the light, people talking about it openly and frankly on social media, writers of various genres including literary fiction speaking about reading it or even writing it. I shouldn’t have to say it, but I will: there is great fanfic out there. Of course, there’s still stigma and disdain, and as a lifelong fandom person I have a lot to say about a lot of aspects of fandom, both negative and positive, and the impact of fanfic on publishing, but, honestly, that’s both boring and long enough to build a dissertation on, so I’ll try not to ramble.

On a craft level, I view the original work I write and fanfic as different genres and therefore I approach them in different ways which, for the most part, don’t have anything to do with each other. Original work is far more ponderous while fanfic has the capacity to come out really quickly and need minimal if any editing. That said, I have written fanfic that, at 40,000+ words, is the length of a shorter novel, and that has been a hands-on lesson I can apply to my original work: First, that I can write something of that length and, if I’m enterprising, longer. Second, that I know how a work of that, or any, length should feel rhythmically, and so writing it is valuable practice that ensures I know how to hit the right narrative beats at the right times. Third, and no doubt some will think me mean-spirited for saying it out loud but it’s true: in a lot of fanfic, even good ones, there are common “tics,” craft moves and phraseology unique to fanfic, that are frankly bad writing and teach me how not to write. Any genre will have these and fanfic is no exception. Some of the best craft lessons involve looking at failed work and asking ourselves what made this piece fail.

I read fanfic for different reasons than I read original work (comfort, escapism, romance, fixing canon, to see what happens in the imagined future of a beloved show, movie, book or comic, in an alternate universe, or if a different choice were made at a pivotal moment, etc.), so when I’m writing it my goals are different too, and the personal stakes are just so much lower. I can blast through writing a piece of fanfiction really quickly and post it the next day if I want. I try to write well for all my work, but in fanfic, not every single word, sentence, paragraph has to be agonized over until it’s pitch perfect. And, if my position in a given fandom is just right, I’ll get the instant gratification of many comments which is, frankly, unheard of when you publish mostly in litmags. And I have friends I’ve made in fandom who are lifelong friends, same as I’ve made in grad school or other writing spaces.

I used to feel really guilty about the time I spent in fandom/fanfic vs. writing original, but it’s become clear to me that my practice of both forms of reading and writing are separate. Fanfic is a hobby I’ve had nearly all my life, and I refuse to feel guilty about spending time and energy on a hobby same as anyone else. Being in the arts during end-stage capitalism can trick you into believing that all your waking moments should be used for the hustle, that any talent or skill you have should be monetized, but that’s neither healthy nor sustainable. Hobbies are brain food. Everyone has hobbies and interests outside their profession. We should get to indulge them without feeling like we’re doing something wrong.

***

JASMINE SAWERS is a Kundiman fellow and graduate of Indiana University’s MFA program whose fiction appears in such journals as AAWW’s The Margins, Foglifter, SmokeLong Quarterly, and more. Their work has won the Ploughshares Emerging Writers’ Contest and the NANO Prize, and has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize, Best of the Net, and Best Small Fictions. Their debut collection, The Anchored World, is available through Rose Metal Press. They serve as an associate fiction editor for Fairy Tale Review. Originally from Buffalo, Sawers now lives outside St. Louis. Learn more at jasminesawers.com and @sawers on Twitter.

***

MYNA CHANG (she/her) is the host of Electric Sheep SF. Her work has been selected for Flash Fiction America (W.W. Norton), Best Small Fictions, CRAFT, and Daily Science Fiction, among others. She has won the Lascaux Prize in Creative Nonfiction and the New Millennium Award in Flash Fiction. Her chapbook The Potential of Radio and Rain will be released by CutBank Books in 2023. Read more at MynaChang.com or find her on Twitter @MynaChang.