Someone left cat food in the extremely haunted basement trash room of my building and it made me so hungry I forgot how creeped out I was being down there for a second. So I hit up a photographer I modeled for a couple times to see if he had work for me, and he did. I’m meeting him at the American Hotel, on the bleeding edge of the Tenderloin, about eight blocks from my apartment, with mascara on.

The Mexican palms en route have no idea it’s winter, but all the leaves on the London planes have browned and crinkled up and died. There’s a weathered white woman crouched outside when I arrive at the mid-rise brick Edwardian, smoking crack from a blackened glass pipe. She asks me what the fuck I’m looking at. I stay silent, look away, like I always do.

They’re calling it the “dot-com bust,” but I never lived here in the boom. San Francisco’s always had a ragged edge, from everything I’ve heard. More ragged some years than others, I guess.

A stranger opens the blinds on a mid-floor window and stares out at me, indistinct behind the glare, before disappearing into the shadows. The brass handle of the entrance door is cold and slightly damp.

The American Hotel looks and feels like it was built right after the 1906 earthquake, San Francisco’s worst day ever. The ceiling has one long, thin crack that makes me nervous, and white latex paint over decades of lead smoothing the edges of the carved molding all around the ceiling and the floor. A brass chandelier holds candle-flame-shaped incandescent bulbs, about a third burned out, and the carpets are…carpets. My roommate-slash-ex-boyfriend and I have a rule in this neighborhood about the three-second rule: there is no three-second rule. If food falls on the floor it should probably be nuked from space. And something tells me this red and green germ jungle has been steam cleaned about as recently as ours has, which was probably the boom. There is a smell, also, an old-building-in-the-Tenderloin smell, like laundry gone sour in a forgotten washing machine, fresh paint, and yellowed wallpaper paste that silverfish and cockroaches eat when they think no one’s looking.

The photographer thumps down the staircase, startling me, gripping his Pentax — a bulky medium-format camera with a wide lens and a walnut handle. He smiles when he sees me and adjusts his glasses. We both glance at the sunken fellow behind the front desk, who has surely seen it all, mopped up everything, called SFPD so many times he just says got another one when they pick up. He stares back blankly, expecting no explanation and unlikely to believe our truth. No really, it’s fine art.

“Janine! Good to see you again!” the photographer says, and means it, and I mean it when I smile back and say, “You too, Paul!”

Paul Hido is not Japanese, as some assume from his name, and I guess his minimalism. He’s a white guy from the Midwest. This did not entirely surprise me the first time we met, at a cafe in North Beach, because the photographs that made him famous are all of lonely American suburbs at twilight, yellow light spilling into the fog through the kitchen window, god knows what microwaved leftover conversation dissolving into argument inside. Anyone who can capture that stifled devastation with the haunting beauty that Paul Hido does has lost one too many hours to a neighborhood that makes you drive to eat.

I’m just glad he’s never taken his dick out in the middle of a shoot. He’s not that kind of photographer, but once it happens, it’s hard to un-imagine it happening every time, and it happened to me the first time I ever modeled for money.

He gestures to the blood-red-carpeted stairs with his free hand. He explains with the glee of an eight-year-old who just found a frog in a ditch, “The elevator’s broken but there’s this neat little hidden alcove on the way up, and the lighting was just, like, spectacular. I think it was on the third floor. I want to see if we can get a few shots before the sun moves.” There’s a second where there’s more in his eyes, when it looks like he has one more thing to say about this alcove, like it’s something more than lighting. But he doesn’t say it.

The pipes groan in the ceiling above us.

We prowl up and down the hallway, past the stains and cigarette burns and unpainted fist-sized spackle patches in the walls.

“It was right here,” Paul says. “I was sure it was right here. Maybe it was the fourth floor.”

We speed walk up the next flight of stairs, making my heart work. The fourth floor hallway smells like bleach.

There is no alcove. Paul’s forehead has achieved a thin sheen — mine probably has, too. He frowns. “Well damn. Maybe we’ll find it later. We should probably get to the room I rented before the light changes too much.”

I nod. I get paid the same no matter where we take the photos.

The room is on the top floor. The sheer curtains look like they were woven out of smokers’ lungs, and the bathroom faucet drips once every three seconds, lending the beat of a moist waltz to the chaos of the street below. Paul has a system of huge black foam boards and orange clamps that, when they’re all arranged just right, create the perfect natural lighting. He does not use artificial lights.

“So, I was thinking we’d start here, on this bed.” He gestures. There is only one bed. It has a polyester duvet printed with dizzy green swirls. I wonder if it’s been washed. Ever. “We’ll take a few warm up shots and then I have some things in the suitcase.” I glance at the suitcase. Ten minutes and two sightly-nervous rolls of Ilford 120 film later, it’s open and I’m wearing a blonde wig. I pout into the green and purple reflections of the Pentax’s wide lens. “Beautiful,” Paul says. “Just like that. Hold that pose.” Click-click. Wind. Click-click. Wind.

He stops to shift the black foam boards into a new position. He has a step stool to reach the curtain rods so he can clamp them up there at exactly the angles that will make me look disappointed and sexy and unreachable and vulnerable all at once. One of the rods has a screw loose in the metal bit that mounts it to the wall. It’s going to — “Paul, the curtain—!”

“Oh shit!”

It swings down, and I grab the foam board as he drops it. He catches the rod and fumbles it down the step stool to the floor. “Shit, shit,” he says, more chagrined, embarrassed than upset.

“Sorry,” I say. I don’t know why, it’s not my fault, but I say it anyway. I lean the foam board gingerly against a wall.

“It’s not your fault.”

“I hope they don’t charge you extra.”

“Ha, yeah, they better not.” He looks at me. “You know what, stay right there. This might be a happy accident.” He replaces the step-stool with the tripod. Click-click. Wind.

“How’s school going?” he asks.

“It’s okay. Oh, I got a new job at a camera shop, actually. Ritz on Polk.”

“Oh? That’s cool. You’re a photo major?”

“Uh, no. That’s my boyfriend.” Click-click. Wind. Boyfriend is my shorthand for whatever the thing is with the roommate. He’s fucking a waitress in West Portal who isn’t into girls, but whatever. Rent’s still too high to live alone here, even in a bust. “But yeah I work at a camera store now, so if you ever want a discount, you know…”

Paul glances at his Pentax. We don’t even stock them at Ritz Camera on Polk. The one in his hand is worth a whole shelf of our Nikon DSLRs. “Yeah,” he says, “Uh, I have a guy I go to in the East Bay to get my film developed. He does really beautiful prints, actually. I could give you his number. You know, for your boyfriend.”

I think of the sweet Asian couple on O’Farrell that my roommate-with-benefights and I take our film to. The big machine we have at Ritz doesn’t come close to what they do in that tiny space. And they have the good matte paper and four different kinds of borders. I hope the digital transition doesn’t put them out of business, but given our nonexistent traffic at the Polk Street Ritz, I kinda already know it will. The future belongs to Paul’s Guy in the East Bay, because photographers like Paul are going to be the only ones who can afford to shoot film soon.

“This old hotel really has so much character, doesn’t it?” Paul asks. Click-click. Wind. “It really makes you think about all the things that have happened here over the years, you know? It was actually kinda spooky here alone.”

I glance at the green duvet where my hand touches it.

“Okay, let’s get a little sexy,” Paul says, looking up from the viewfinder. “What kind of panties are you wearing?”

I cringe a little at the word panties, but can’t exactly articulate why. “They’re kinda lacey,” I say. “Nude colored.” I take off my jeans and lie down across the green duvet on my side, so my hips look wider than they really are.

“That’s really nice, just like that,” he says. “Can you lean on your elbow?”

“How about the shirt?”

“Leave it on, that pink is actually perfect against the green blanket.” Click-click. Wind. Calling it a blanket feels overly generous, but I keep my lips just slightly parted, instead of dropping snark. “Hold that pose for a second,” Paul says. “Just like that. Don’t move.” He winds the film, pops the back of the Pentax, and seals the 120 roll with a strip of adhesive paper. Loads a new one. “Okay, uh, tilt your head just a little toward the window. Yeah that’s perfect.” Click-click. Wind.

I do think about all the things this room has seen. The flapper dresses on the floor, the men with liquor bottles in one hand, sobbing into the other, socks clinging to their naked calves with garters. The cum on every wall, the hundred thousand cigarettes, the countless toilet-hugging-vomit-nights, the sloppy ponytails and the smeared eyeliner, all the things the photographs that we’re creating will evoke but never say explicitly. The moans, the tears, the screams, the overdoses and the budget-conscious tourists who wished all night they’d shelled out for the better place on Geary Street.

We wrap up and I put my jeans and jacket back on, pack the wig back in the suitcase. Paul pulls down the foam board and the clamps, collapses his Manfrotto tripod. The bathroom faucet drips, drips. A car bleats like a lost Stegosaurus outside at the intersection.

“Uh, how about I walk you down before packing up,” Paul says. “I want to see if the elevator’s working again, just in case. Carrying all that gear up the stairs was kind of a hassle.”

The lift clanks into motion when he hits the down button, and grudgingly clatters up to our floor, a cage of fluorescent and scratched paint and linoleum inching up behind the black and rusted iron gate. I slide it open, careful to keep my fingers out of the metalwork as it folds back into the frame. It’s just like the one in my building. It even has the same Schindler logo on the back wall. I’ve yet to actually watch Schindler’s List at age 20, but I know it’s about Nazis, so I just think of Nazis every time I see the name. Paul taps L for Lobby on the column of black buttons and we clank into a slow descent.

“How are your kids?” I ask. I hope I’m remembering this right and he has more than one.

“Uh, you know it’s actually been really hard with their m—”

The elevator jolts to a sudden stop.

We both have to catch our balance.

“Earthquake?” Paul asks, voice a little higher than I’m used to.

I shrug. Everything is settled now, whatever it was.

There’s still at least six inches between the yellow linoleum under our feet and the red carpet of the hallway of whatever floor this is. “Ha, maybe we should take the stairs the rest of the way,” I say, laughing a little to shake off the jump scare. He agrees with his own nervous laughter, and I realize it’s a little more nervous than mine. I don’t think he’s ever lived in a place like this. He picked it out because it was the seediest hotel he could find without actually contracting a disease, I’m sure, but he lives in a big house in a nice part of Oakland and I’ve been in the Tenderloin for two years. This is my domain, not his.

We exit the lift with a short hop down and look around. The stairs are left. Paul heads right.

“Uh, Paul, the stairs are —”

“I know, but I think this is it!” he says. “The alcove I found earlier.”

I follow him around a corner. There’s a corner past the corner, and a bare window with no blinds or curtains, and the rug is faded nearly pink except for a red square where a lounge chair used to be. There’s a hole in the wall where an outlet lived, once, two wires still sticking out like severed nerves. Whatever light impressed him earlier must be long gone, it’s all reflected from the brick across the alley now, and the fog is coming in so it’s just dim and gray.

“This is even better lighting than earlier,” Paul says. “Hold on.” He makes for the elevator. “Can you stay for like, one more roll?”

“Sure.”

“Okay, I’ll be right back.” He runs to the stairs to get his camera.

I lean against the wall. I wish the lounge chair was still there, and for a moment I imagine I can see it, leather from a time when this place could afford it.

I smell pot smoke from a room nearby. I breathe it in.

Someone laughs.

An old song plays on a plaster-muffled radio. Hot town, summer in the city…

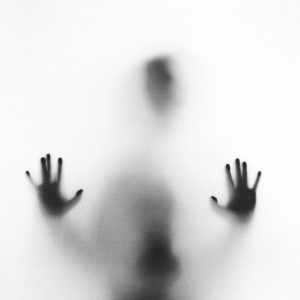

And then the chair is there, cracked brown leather with a low back and wide arms, and I blink and there’s a blonde girl in it, my age with bell-bottom corduroys and platform shoes and freckles and a button nose, and I feel like I should look away, but I can’t, I don’t want to. She gestures with a dancer’s wrists at a lanky Black guy with a tight shirt and an Afro, who leans in for a kiss and fumbles at her halter top. Come on, let’s go to our room, she says, more echo than voice, and he says, No one’s going to find us back here, and she giggles and he drops to his knees between her legs and gazes up at her face in the moonlight like he’s about to propose. And she looks back like she’s about to say yes even if he doesn’t ask. He reaches for her brass belt buckle and the room skips a beat.

A long black scuff mars the chair’s side. A man with a salt-and-pepper mullet stands at the window, gold light pouring in across his brown skin and his blue plaid shirt, hands clenched in the pockets of his acid-washed jeans. He sniffs. A square-jawed white guy with a dishwater mustache leans up against the window frame and offers him a cigarette. Plaid throws him a disapproving look. Mustache puts the cigs away and scratches his chin. So. What’d the doctor say? he asks.

Plaid shakes his head, and his clean-shaved chin quivers. Mustache rushes in to hold him, one arm tight around his waist and the other strong across his back. Fuck. Fuck I’m so sorry.

You didn’t know.

And they hold each other. And they both cry. And then they kiss and wipe each other’s tears. Fuck it, Plaid says. Fuck it, let’s move in together. I’m so sick of hiding and I don’t know what the fucking point is anymore, and god knows how much time we have left, you know?

Mustache nods, and holds him even tighter as they flicker and fade.

The chair loses its legs and drops three inches to the carpet in a flash. A gash erupts across the back, and black tape materializes to heal the wound. An Asian woman, Filipina I think, just a little older than me, rolls her suitcase in and tears her headphones off as she flops onto the sunken leather seat. They dangle from the Walkman in her purse, playing Smells Like Teen Spirit at a volume I’m pretty sure the front desk guy can hear.

That self-absorbed pretentious fucking bigot! She yells, punching the leather arm of the chair. Damn him! She throws her hands over her face and screams into them.

She blows her nose into her denim sleeve, black mascara smeared all down her cheeks. I hope you fucking burn in Hell, Angelo, she whispers. Two deep breaths. And Satan molests you with a spatula while you’re down there.

She giggle-snorts. And then she sighs, and turns toward the window, where it’s raining, and she smiles.

Her smile tugs at me, plucking some chord I don’t have a name for yet, in the hidden alcove on whatever floor this is of the American Hotel. It pulls me in like Naan ‘n Curry when I’m walking home after a long shift popping bubble wrap in an empty camera store.

“Hi,” Paul says behind me. I jump. The chair is gone, the woman is gone, Nirvana has left the building. Paul Hido stands in the alcove entrance with his Pentax and says, “Uh, sorry. I didn’t mean to startle you.”

“I — no, it’s okay —”

He glances at the red square, and back at me. “You saw them too, didn’t you?”

I wonder what he means, because I’m certain that whatever I just saw was my imagination, but — but then I nod, because of course the hidden alcove on the unnamed floor of the American Hotel at the edge of Tenderloin is haunted. Of course it is. The whole neighborhood is haunted.

Paul looks at the window and the brick and fog outside. “You know what, the light’s not as good as I thought it was.”

We head back to the elevator, think better of it, take the stairs. He pauses before we get to the lobby and pulls some cash out of his wallet. “Here. Two hundred. I’ll send you the contact sheets in a few weeks so you can see how these turned out.”

“Thanks.” I slip the bills into the front pocket of my jeans next to my chapstick. They’ll cover groceries til my next paycheck, plus Naan ‘n Curry tonight. “That alcove…”

“Yeah, sorry we wasted time on that.”

I shake my head. I whisper, “What did you see in there?”

He looks off into the distance, at the candle-flame-bulb chandelier, maybe. And he says, “It was like… I don’t know how to describe it. It felt…” He shakes his head.

“There’s this place in the basement of my building,” I say, “where we have to take the trash,” I don’t mention the cat food, “and every time I go down there I just feel so freaked out for no reason, like I’m sure somebody was murdered down there. It’s haunted as fuck, in a bad way. That alcove felt like —”

“Like the opposite of that,” he says. Soft.

“Yeah.”

“I wanted to capture that.” He holds his Pentax up close to his chest like a kitten.

“It would’ve been a whole different mood for you.”

“I know.”

“Next time?”

He nods. I smile.

Outside, the woman who was smoking crack is talking to a social worker and there’s someone pissing on the corner of the building.

I look away, like I always do, and walk downhill to Market Street. I’ll catch the F to Safeway and get human food, not cat food.

I wonder if my haunted-ass building has an alcove somewhere, where it keeps its favorite memories.

Maybe that’s where the cat lives.