We’d put the white wasteland of the Tiberius Peninsula behind us when the doctor told me about his last expedition and how badly it had gone. How men he’d trusted for years had just thrown their hands up when the chips fell. How some had gone so far as to claim to have different jobs; be different people. A biologist, a woman with twenty years’ experience studying ice fauna, had turned one of their rifles over in her hands, brushing the tundra floor with the weapon’s shoulder stock.

“This place is so filthy,” she’d said, sucking her teeth. “No wonder you needed to hire a maid. I will warn you, however: this project could take quite a long time.”

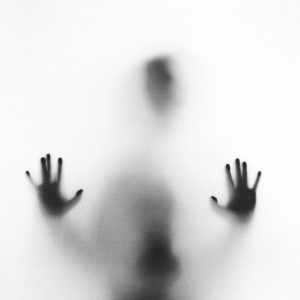

The doctor said that when they’d found her in her tent the next morning, her lips had frozen against the blue metal of the same rifle, fused now with a tunnel that began with the weapon’s barrel and ended with a gristle-tipped caldera in the back of her skull.

I wondered if the biologist had assumed the rifle was a broom until the end, and I said as much. The doctor didn’t answer, though, focusing instead on the endless blank ahead of our sled and dogs. Ahead of us, behind us, on every side. That was the trouble with the doctor: if he thought I wasn’t paying attention for a second, he’d stay on me, buzzing in my ears like an overeducated mosquito or a needy housecat. But the moment I said something, he’d be too busy staring into the great unknown to acknowledge my existence. I’m just the musher though: the Arctic equivalent of a taxi driver. He’s some doctor scouring the frozen wastes for god only knows what. We are not the same.

We get to a good spot for camp, and not a minute too soon. The snow’s coming in hard, and a whiteout’s inevitable. Nothing to be done now but set our tents and wait. The fire comes eventually but isn’t my best or most efficient. Something about it feels sloppy, like I haven’t been doing this since I was a kid. I don’t know why, but I blame the doctor for it. His presence, the way he acts around me, it’s all got me second guessing myself, which in the wastes is a good way to get yourself dead, dead, dead. He seems to appreciate the warmth, though, sitting on his stool as close to the fire as he can bear while he scrawls something in that journal of his. I’m staring at him, and I don’t know why. He finally acknowledges my presence, raising his eyes from his journal long enough to give a curt, short nod. It doesn’t feel good. It feels like the approval you’d give livestock.

Good dog.

He’s a long, thin man: hard like bones and knapped flint. His mouth is long and fishlike, and I almost expect to see it completely encircle his head like a reptile. With his pale skin and severe face, he’s built almost entirely my opposite. I check on the dog pile, partially out of responsibility to the dogs and partially to have something to do other than maybe get into an argument with the doctor. They’re piled tight together, all interlocking plates and grasping feelers. I drop a handful of dried seaweed next to them as a treat, but they don’t move. It’s just too damn cold for seaweed. They’re good dogs, I decide. Let them sleep. It was a long drive, to boot. The longer we go, the more they eat. And after a journey like today, my guess is that they’ve had about all the ice they can stomach. One of the younger members of the pack on the edges of the pile whines softly in its sleep—a sound like rubber and patent leather squeaking together. I caress the steaming dog’s chitinous plates and the sound subsides as it locks further into the pile, sealing its heat inside.

“They eat microorganisms that they pull out of the ice as they move,” says the doctor, still not looking up from his journal. I’m not sure if he was watching me and the dogs and inferred my interest or if he just likes the sound of his own voice. Probably both.

“I knew that, I think,” I say. “Just something I picked up over the years.”

“As a musher, yes,” says the doctor, looking up at me again with a strange little smile. It’s like he’s got a secret that he’s just barely able to keep to himself. Like most things about him, I don’t like this. “The dozens of maxillae in a sled dog’s face are capable of pulling thousands of microorganisms from the ice in split seconds, even as they skitter over the ice.”

I cast a glance back at the pile of carapace again: about a dozen sled dogs, all told, each roughly the size and weight of a city manhole cover. Their plates, an unmistakable icy blue, is already disappearing beneath a layer of obfuscating snow. Soon their little pile will resemble nothing so much as a shallow igloo without an entrance, the sled dogs playing both the role of sheltered and shelter. The soft, clicking sound of their gentle snores are the only thing suggesting that they even live. It’s a sound that will hang over our encampment for the rest of the night.

###

I don’t remember sleeping, though I’m sure I did. The Tiberian Wastes turn everything into a white blur—like a dream you can’t remember, but feel certain happened. The doctor’s at the campfire as if he never left, and the yellow-white sun renders his humble cooking fire nearly invisible. We drink black coffee and let the sled dogs graze a bit, slowly growing more active as the pitiful rays of the sun do what they can to warm their shells. Their satisfied little gulps and gasps grow louder as they take more nutrition from the ice and grow more alive with the light. There are flashes of their sucking mouthparts that stretch out and are gone all at once. They shuffle along the ice in little packs, their faces down and away like guilty gossips.

The drive goes without event, and when we stop to set up camp the doctor tells me we’re nearly there, but I swear I don’t feel as if we’ve made any progress at all. I still haven’t asked where “there” is, even though I know it’s the sort of information that can mean the difference between life and death in the wastes. I don’t want to die out here, but when I attempt to meet eyes with the doctor over our latest pitiful fire, I see only apathy and contempt: the face of a man who sees most everyone around him as something piteous and beneath him. He is eating the last of our rations and I’m aware that I haven’t eaten anything at all. Am I hungry? I’m not sure. The cold slides across the skin like a knife peeling away scales from a fish. I check on the sled dogs again and, satisfied with their clicking pile of snoring chitin, I crawl inside my little tent, leaving the doctor, who hasn’t even begun to pitch his. I could offer to help, but I don’t. It’s my tiny act of defiance. But he doesn’t call out to me at any point in the evening. He doesn’t interrupt my sleep when it finally comes.

It’s a bear that wakes me.

It’s twenty feet tall in the black and snow, and drags a hand of spikes over the exposed belly of a sled dog. The dog squeals in the darkness, a sound like steam escaping a broken pipe, and its endless legs wriggle and squeeze as great gasps of air and screaming vapor escape into the sky. The great pile of sled dogs chitters in fear or apathetic sleep: it’s impossible to say. Perhaps they know, as I do, that the bear will finish this meal and move on, bringing the remains to its clutch of cubs in some clandestine snow-packed den somewhere. I watch from a gap in my tent, not daring even to breathe. The bear’s mandibles make short work of the soft pieces of the dead sled dog, carving it apart and inserting gobbets of meat into a soft, fangless mouth that droops like an old man’s gummy lips. The serrated bone blades are precise and perfect, more like the work of a surgeon than a butcher, until there’s nothing left but shell and hollow antennae. When the bear leaves, I swear it looks me over, and I tremble to see it so close. Its mandibles have contracted into its loose skin pouch of a mouth, and in the dark its face is like a melting candle with tiny pinpricks for eyes somewhere in the deep, black recesses of its ocular sockets.

I won’t fall asleep until hours after it’s gone.

###

The loss of one sled dog won’t slow us down too much, though I mourn its absence.

They’re good dogs.

Once again the doctor has beaten me to a morning fire, and I see that he’s cooking now. There’s a smell like red cabbage and old venison, and I see with horror that he’s roasting another of the sled dogs in its shell. I stand in stunned silence as he takes the great, shining beast on its spit and drops it into a nearby pile of snow, where it sizzles and hisses. The sound makes the pile of living sled dogs warble and cheep in some slowly rotating defense position. The doctor has his back to me as he leans over his feast.

“One dead and they run in columns of two,” he’s muttering. “Odd numbers will only slow us down. Besides.”

And he turns to me with a great chunk of cooked meat. It’s two big for one hand, white and fatty and run through with a lacework of blood vessels now hardened and cauterized in the cooking process.

“We have to eat,” he says as he stoops once again over the sled dog, taking it apart with a small pocket knife. He’s like the bear: precise and delicate. Nothing’s wasted, and I know it’s enough meat to last us another day or two.

The sled dog tastes of fat and salt and little else. I’m disgusted by it. I keep eating. It’s exceedingly rich and it feels wrong to eat it on a hardened pile of snow in the middle of the Wastes. I can’t finish it, and put the fist-sized clump of meat into my pocket, where I’ll graze on it for the rest of the day.

The doctor is scrawling in his journal when I go to harness the remaining sled dogs. The first one screams at me, rubbing its blunt, chitinous mouth parts together in a threat stance. Without missing a beat, I strike it around what little bit of its head is visible outside of the protective shell. It makes another screeching sound, quieter this time, but does not attempt to stop me from applying its harness. I won’t have any trouble with the other dogs. I’m not proud of this, but there’s no room for anything but obedience during this trek. To allow any sort of defiance is to welcome death into your camp.

The doctor’s finished whatever he’s writing in his journal by the time I’ve harnassed the dogs to the sled, and that means it’s time to continue. More barren wasteland passes under and around our eyes. Snowbanks and frozen, secret springs. It feels entirely dead, but the very presence of the sled dogs proves that isn’t true. They slurp and gulp down the microorganism that live in the ice; organisms that will continue to thrive and reproduce long after we’ve continued past. Life continues under our feet, even if it isn’t the sort of life we can easily identify.

###

The sun has just passed over the horizon when we spot the building in the distance. Squat and gray, like a place meant to house livestock. Any semblance of power has long since given out, and with it, all signs of life. One last fire before the big unveiling. One last mouthful of torn dog meat before we open those doors and investigate. One last sleep before the doctor gets what he’s after. I don’t know what happens after that.

I build the fire tonight, and I’m surprised at how pathetic it is. My fingers slip on the dried stakes of birch and the preserved pieces of fatwood. The cold is pins and needles of ice in my fingertips, but I’ve done this before, haven’t I? It’s embarrassing, like a parent’s failure in front of their impressionable child. The doctor doesn’t say anything; he barely registers my movements, but when the deed is done, I swear I can see his eyes flick up to me in the infant yellow of the fire with a playful pull around his eyes that seems to say “good dog.” I start for my portion of dog meat, but remember that it’s only because of this strange academic that I have any food at all, and decide against it for now. I’ll eat privately in my tent, I decide. No sense in letting him have another thing to smirk over.

Why was there so little food left? I tell myself it’s his fault: that the doctor gave me bad information. Amateur information. But I don’t think that’s true, and I can’t remember why. Had we agreed to hunt while we were in the wastes? Would I really have agreed to something like that?

“In the army, they told us that a soldier marches on his stomach,” the doctor says, startling me with the strength of his voice. “Do you remember that?”

I’m having a hard time imagining a man like this enlisting in the army, but I’m surprised that he’s right. I do remember something like that, though I barely remember the army anymore.

“A farmer’s just as important as a warrior, despite what some people might tell you. Of course, that’s abundantly clear when you’re starving in a trench. Plenty of bullets, but not a bowl of soup to your name.”

In the blistering cold, a hot bowl of soup, even the mental impression of it, feels like some sort of holy balm: sacred and nourishing.

“And after the last great conflict I came here with some others. Some other over-educated survivors who would rather hold a plough than a sword or a shotgun.”

I think of the biologist who imagined herself as a maid. I think about all her imagination and intelligence and good intentions sprayed against a wall somewhere in that looming gray building.

“But when the only safe place to grow is the Tiberius Wastes, you’ve got to reinvent the plough,” the doctor says, standing up and wiping his hands on his fur-lined trousers. “And there’s just no time.”

He crosses past the fire, and I’m surprised to notice for the first time that he’s already pitched his tent. He pulls open a flap and turns back to me, his eyes glinting in the firelight.

“You didn’t pack enough rations,” he says. “Because there weren’t enough rations to pack.”

As I’m falling asleep, I imagine another great bear, twice as big as the last one. A beast the size of an Onoda battle tank. I dream of its dripping, fleshy maw. I dream that it tears me to shreds and doesn’t bother to consume what little ribbons of flesh are left over. I dream of my obliteration.

###

The doctor hasn’t built a fire the next morning. His tent is gone, and he’s nowhere to be seen. The short drive to the structure takes less time than it should, which I attribute to the lightened load. The sled dogs pull ahead, leaving furrows in the ice where their sucking mouthparts have scoured and scraped for nourishment.

The building is somehow even more featureless close-up. It’s wide and squat and windowless: a great ugly box. A desperate turn of a pneumatic seal lets me inside and I realize my first impression of the structure was the right one. The interior is wide open, with rows of stables roughly constructed from aluminum and cast iron. The floor is smooth with hoarfrost, with regular drain placements that connect… somewhere. It feels too quiet almost immediately. As if the space should be filled with mating calls and braying and screams.

It’s a barn.

Almost on instinct I go back outside and untether the sled dogs. They immediately seem to understand and scuttle their way into the gray building, making their curious creaking sounds and investigating the barn’s wide spaces. I do not call out the doctor’s name and I think I know why. The futility of the whole space makes it pointless. There’s no livestock here. This is just a box to hide failure in. A sack for drowning kittens.

A cluster of sled dogs have gathered around the entrance to one of the stables, their antennae wriggling in excitement and anticipation. They’ve found something. It takes a moment to push several of them aside gently with my boot before I have the room to pull the industrial metal door open. When I do, I expect them to flood inside and begin excitedly investigating, but they stay where they are. Several inch further away from the entrance now. The room is small and somehow even colder than the powerless barn. The floor is bare tundra, like an ice fisherman’s shack, with a figure hunched over in the cold, face pressed against the icy bottom like someone lapping water from a low, shallow stream. He’s dressed in the warm, practical furs and leathers of the tribes who call the outskirts of the Tiberius Wastes their home. His hands are pressed on either side, obscuring the face, and his knees have welded to the floor, his rear end sticking upward like a lover or a cartoon character expecting a comically large boot to his posterior. Resting on his motionless back is the doctor’s journal, open and face down as if the man was a coffee table, the journal a pulp fiction page-turner that you’re planning on returning to just as soon as you get another cup of coffee. Both man and journal are completely still, just as I left them.

The journal is filled with my handwriting. With my notes, each one desperately scrawled, the way a dehydrated man might write out his demands for water. Charts of the sled dogs, of their feelers and grasping, sucking mouthparts. Scribbles of their prey: the tiny creatures under a microscope, though I was never much of an artist. Notes on how their mouths and dietary needs are different from ours.

Notes on how they’re the same.

At some point, they begin detailing the journey here, telling anecdotes about the musher’s capabilities as a pilot and his obvious dislike for me. About the bear and killing the dog for meat and how clear it was that the guide hated me for such a thing. Except he had never been there. He had always been in this room.

One of the braver sled dogs has chittered into the testing room and snuffles around the fallen man. The heat of the dog’s underbelly loosens something in his stiffened arm and it slips downward, answering a call to gravity. His face has more in common with the bear’s face than the dog’s, despite the ultimate goal of the experiments. His mouth is slack and stretched out, like a sleeve made of skin and stubble, lips sealed against the ice in a grotesque attempt at a vacuum. His eyes should be shut, but the elastic pull of his cheeks and lips hold the dead sockets open: a man staring at his last meal. Vessels in his eyes and skin have exploded, leaving crater marks of black, blue and red, like a gaseous planet somewhere far away from here. It’s beautiful in its own way. He would have been more beautiful if the test had succeeded. But I had to learn the hard way: man cannot live on microorganisms alone.

Technically, I suppose, it was the musher who learned the hardest.

Oh well. Omelets. Broken eggs. Et cetera.

I know that in the adjoining stalls there are more of them. Dozens of them, mostly chosen from the surrounding wasteland tribes. This is just the one I saw last.

The final entry in the journal, written in small, devastatingly careful handwriting:

“Hunger makes a beast of any man.”

###

The sled dogs have abandoned the building far faster than I expected them to. Perhaps they know what I know: there’s nothing to eat here. Their harnesses are too small for my body but fit around my neck with very little effort. It’s so cold, but I pretend that I can’t feel it. A sled dog has no concern for the cold. I’m getting hungry, but I pretend not to notice. A sled dog can find food anywhere in the wastes. As the sun goes down, I think that I can see a bear in the distance, the loose, rubbery skin of its mouth already peeling back to reveal blackened tusks and a gaping maw. I think I can see it. At least I hope I can.

Someone should eat well tonight. It won’t be me.