She was born in the Cave, emerged from the cocoon of shattered stalactites soaked in vestigial groundwater like all daughters before her.

Her first name was Kori, her second, Mama, and now finally everyone calls her Yaya, the eldest. Even after so long, a sinful child whose hunger for adventure once lured her old family to its demise and left her all alone. But a name is a living thing, and she cannot stop its shifting any more than halting her lungs filling with sand, her voice turning to glass, and her bones displaced by wood heavier than logs the sons carried from the Forest.

Silt too fine for the quickness of young eyes to notice covers the Cave floor and grates her soles, seeps into her, slowing all of her down. Her movements, her breathing. The world.

Her eyes gather clay over their membranes, and in her patient sight, she sees more. Where the red sun shines from the skylight, the rock grows richer with in-between hues she cannot name. Then shapes: a jagged rock with nostrils, outcrops mouth-shaped. Before their souls and bodies settle on the bedrock, the dead populate the walls, and only her elderly eyes can witness them.

Soon, she’ll join them, too, and the stone will forever cover the weight of her regret.

###

Another child crowns within a granite crevice, head-first, its wispy white hair sprinkled with grime, and Yaya knows it’ll be the last time she helps the Cave give birth. With this new progeny, their family will number a total of fifteen. The Cave has never sustained this many before.

Yaya squeezes her fingertips first around the bulbous head shape, pierces through into the familiar wet-warm roughness of cavernous innards. Her skin is used to it now, it doesn’t sting, but more important than resilience, she has learned precision: to feel her way through runny ore, slow so crystals won’t scratch at her invasion.

Her hands wrap around the child’s pelvis, and though she expects a son’s shape, there’s absence between the legs. Slowly she pulls the child out, curious that this daughter had not sprouted from stalactite. The innards were the domain of men, always had been, to build bodies thick that walk the Forest’s coldness and muscled thighs to flee from the Prowler.

Rock shuffles beside her skin as she thrusts her arms elbow-deep, and instead of the baby, an ancestor’s face emerges on granite: wrinkled with outcrops, an oversized pebble of a nose, a borehole mouth. The rock whispers to her. A voice that reminds her of her first Baba’s, but much sharper, honed with a blade to cut. She has not heard a masculine voice older than her since the Fog claimed all men who came before her.

But it is not a conscious voice, it only repeats one word like a geyser: puuuuuush, puuuuuuuush, puuuuuuuuuuush.

The soul of a precursor whose mind has dulled—now an appendage of the Cave, docilely moving the rocky womb to assist the birth.

Yaya eases out the baby, determined to do the Cave’s bidding, as she has done many times before. The girl comes out, easier than most boys Yaya has unearthed, quieter than most girls she scavenged from stalactite-wrapped husks. She is small in size. Her eyes mismatched, one brown like her own, one gray like ash. Yaya is aware some of her family watches—three daughters old enough to be called Mama are plucking tufts of grain from the ground behind her, and one son thick-bearded and two heads taller, a Baba sharpening his spear with flint some feet besides. They whisper to themselves, deluded that Yaya’s hearing is already gone.

They are old enough to have tasted the grotesque spices of life but young enough to yield to fear still. This child is different, and different is danger. Different is the sudden absence of fruit, forcing sons out earlier, still exhausted from the last hunt. Different is the stories Babas say of yellow eyes between the trees, and fangs so sharp they rend flesh from bone in single bites. Of the Prowler coming to feast on sons of the Cave.

But Yaya knows the Cave never betrays its children. Even when its maw shut early, pulling the rock inward like an old woman’s puckered lips around a pebblefruit, leaving her Baba out for the Prowler to devour, it was to keep the Fog out. It was the Fog that came early, and Yaya—then Kori—that disobeyed the rules, and Baba had to save her. It was Yaya’s sinful fault, not the Cave’s.

Yaya is the eldest now, the leader. No longer a daughter unable to withhold foolish dreams, inviting danger for her protector. Not one to let any harm come to her family, ever again.

And this child, like everything else birthed by the Cave and like the Cave itself, is family.

###

Yaya tends to Kori, the youngest. She peels cave fruit with sharp fingernails and crushes it under her teeth to grind the pebbly seeds before spitting the pulp into Kori’s mouth while it’s still all gums and no bite. She shares tales of the son-devouring Prowler whose blinding gaze turns eyes to mud and how there will come a time when the generations of Cave children that have crusted to stone will walk free in the Forest once more to flatten the beast. And the outside world will be open for all to share.

As she says that, she finds her own chest brimming with warm pride and anticipation; almost enough to counter shame. Whatever errors she made in the past, she will one day walk the Forest and end the Prowler alongside her kin.

Kori’s skin is pink like salt rock, but her puffy cheeks are soft against Yaya’s weathered palms. Kori’s tongue, ash-gray, curls around the pulverized core, swallows it hungrily in one gulp, then mouths Yaya’s thumb. Yaya feels a pebble poking beneath the child’s upper lip, the daughter’s first tooth searching for purchase on her skin.

###

After three risings of the red sun, Kori has grown enough to help with the gathering of fruit, deep in the meandering corridors of the Cave. Yaya shows her the way to inhale as she plunges hands deep where the amber bulbs glow, to find the stem, cut it from the root and unearth the whole vine and the fruits hiding within.

“Tell me about the Prowler,” Kori says as Yaya adds plucked fruit into her basket.

“I’ve told you all there is to know.”

“Why is he alive still? So many strong Babas have walked the Forest. They could outnumber him. Why do we have to wait for the Cave to resurrect everyone? Why do they not all point their spears at him?”

Yaya does not answer, not immediately. Young sons—the Yioi, the ones who share the name Yios—are taught by Babas to ask little, because questioning in the Forest is doubt, delay, danger. A Yios must take orders without hesitation or doubt. But Yaya teaches all of the Koris, and she does not stifle curiosity. Instead, she ingrains patience upon them. And this Kori asks with too much hurry, not letting one question settle before the next.

Kori is not good at being patient. Yaya can tell by the cadence of her pacing, the way her footsteps thud a louder echo, and she’s about to clumsily step on precious grain before Yaya extends an arm to halt her.

Yaya points down, her ankles aching at the thought of crouching, and Kori hurries to cut the grain from root.

“Gently,” Yaya says, and Kori’s movements become slower, though in a way that betrays repressed hurry. She’ll learn with time.

“There is an order to things,” Yaya says. “Once, the children of the Cave roamed the world freely. It was a time the Forest was bright with a sun shining green, the ground clear of swampy sink traps and covered in smooth slate warm on the feet.”

Entranced by the story, Kori’s hands caress in gentler motion, an honest slowness because she wants to take in Yaya’s words. “The Cave warned its children not to stray. But there were no Yayas then, nor Babas and Mamas. Only youthful Yioi and Koris roamed too far, excited by the youth of the world. The Koris were the boldest, reaching the brink of the forest, until their scents tempted a creature out of its slumber.

“The soul-starved demon.”

Yaya caresses Kori’s warm, bone-white neck and beckons her to pass on the grain before it breaks apart in Kori’s shuddering hands. She rubs Kori’s back, feeling her cobbled spine. Upright and proud, as hers once was.

“The Prowler,” Yaya says as they continue their march, “carried the Fog with him like a cloak, pouncing after the daughters. The Cave could not reach their screams as they ran from the Prowler, as the beast swallowed their soft bodies with every leap. The Yioi tried to protect them, blocking the path and taking the Prowler’s bites with their hard bodies. But the Fog softened their flesh with its insidious flame, formed cracks along their granite muscles.”

“Granite doesn’t burn,” Kori says.

“Fog flame is not the same as the bonfire bloomed by flint and grain. Most Koris survived, but none of the Yioi did. The sun turned red, sprayed by the vapors of their own blood and the dancing of the Fog that had found new prey.

“It’s the sin of daughters that brought the beast here, but it’s the sons that carry the burden. Their bodies are hard, with gravelly grips that crush the delicate fruits of the cave, yet serpentinite thighs to run from the fangs of the Prowler.”

“But they die still,” Kori says. “No one survives to be as old as you.”

They take a turn in the tunnel, and amber light shines on them—another fruit, one large enough to illuminate the whole corridor. Kori’s face is pinned on Yaya, her left cheek doused in the lava glow, the right one shadowed, gypsum-gray like a Mama. This daughter has fire that makes even Yaya’s own youth seem timid by comparison. Fire that cannot be quenched before it burns trees along the way.

Yaya points to the light source. “Your turn to pluck fruit. Wrap your hands gently around the bud, feel your way down the stem, and wrest it from its mantle.”

Kori does as she is told, her palms entombing the amber light, casting fluttering shadow fingers along the tunnel.

Yaya steps closer, lowering her voice to a soothing whisper to calm Kori’s first attempt with the cave’s most dangerous fruit. “After the first sons sacrificed themselves, the daughters ran until they reached warm slate again. The Cave felt their fear, the stony earth undulated under their feet, melted and sucked them in, back in the bedrock from which the chain began. The Cave withdrew the magma to form a thicker womb to ward against the Prowler and the Fog.

“Mud and swamp crawled in, and trees sprouted in slate’s absence. In Fog and Forest, the Prowler began his eternal hunt. Although the Cave fell silent after that, She produced more sons than daughters, because it was Yioi that could withstand the Prowler.”

Kori pushes her arms elbow-deep. She’s doing well. “But,” Kori says. “Only daughters came back. Maybe they were better at it.”

“They came back only because sons sacrificed themselves.” Like Yaya’s own Baba sacrificed himself, a story of daughters too wild repeating itself.

“Well, maybe the Cave has made them stronger since then. Maybe it’s why she nourished me in the belly of sons. I beat Yios in a wrestling match. Tackled him down good.”

Yaya sees in Kori a foolhardiness worse than her own used to be. Yios and Kori have never before played this way with one another, but they are the youngest and she can’t separate them. Daughters and sons must be united, or the Cave may fall from within.

Yaya stills her voice to strictness, rock-hard. “No Yios survives to be more than a Baba, but a Kori would not survive to even be a Mama.”

But she regrets her words. They’re oil to the flame.

Kori’s arms clench. “I could.”

A shrill yelp escapes Kori as her arms rush to get out, and Yaya can tell most of the stem shatters by the gray powder scattering over the floor as Kori reveals a torn silver vine with pulsating fruit. Her skin is sliced because the crystals fought back, and she bleeds on the hungry buds.

The fruit pulses violently, angry at the taste of blood. Yaya plucks it from Kori’s hands and hurls it far before she hurries to cover Kori in her embrace. The fruit explodes, sending pebbly seeds hurling on Yaya’s weathered back, one hitting the crook of her spine enough to make sharp sting spike up her skull.

But Yaya does not show pain—refuses to flinch. Because she knows the guilt that comes from hurting those you love, how a grimace of pain can haunt you forever.

“I’m sorry, Yaya,” Kori says, tears tinging her voice before her eyes.

“It’s the fruit that should be sorry,” Yaya says, knowing a smile can mend a memory before regret is formed.

###

Yaya teaches Kori how to grind powder from the Cave’s deep tunnels to spice. Blue salt shines on its own, illuminating where the red sun cannot reach.

“Where the rock reflects green,” she instructs, “you’ll know it’s soft. Find flint sharp enough. Feel them with your hands first, then rub and scoop the dust in your palms.”

There are two Mamas as well beside them, backs bending, spines stalagmite-grafted and gypsum-grayed. They insisted because spice is needed to elevate the fruit from unfulfilling blandness, and they cannot rely on Kori. Yaya considers this unwise because more eyes watching can make pride cloud patience. And she is right.

Kori is shaky, quick to anger at failing.

Although Yaya warns against rushing the grinding, Kori rubs furiously against the green stone, and the whole rock is dislocated. It shatters to smithereens too fine to grind and too chunky to use as spice.

The Mamas say nothing but in a way that says everything. Yaya hurries to scoops the fragments, and says, “This will make for a unique meal, once I pulverize them.”

But Kori remains deflated, the rock-bones of her shoulders receded. For the rest of the gathering, Kori’s eyes remain fixed on the path from which they came, and Yaya knows she is looking beyond that. To an outside world she heard from Babas around the bonfire, of swamps that swallow tree giants and of flying rodents whose fur glistens in beautiful moonlight colors. The Forest, which a young daughter’s mind, balloons into a place of enchanted mystery and adventure. Even the stories of fleeing furry monsters made stars sparkle in Kori’s eyes.

Yaya knows it’s merciful to shatter such dreams to smithereens like the greenstone fragments she now carries in the pretense they’re still useful. But in her heart she cannot bring herself to do it. Some illusions are precious, conjuring beauty when there is none to be found.

###

A suspicion has grown within Yaya that Kori will attempt to escape the Cave and go where only sons may. Like Yaya herself, Kori will plot to wear the guise of Yios—the youngest son—when her fingernails grow sharp enough to rend. But when Yaya finds the torn white hair stained in blood tucked beneath the bed of leaves, her hardened muscles tremor with dread. Kori’s nails are still dull, much duller than Yaya’s were when she’d tried this.

Kori did not cut her hair with nails; she tore it from the stem with flint.

Yaya curses herself as she rushes to the maw. The eldest should keep her ears perked for rock-whispers and face the omens before they fester. She has grown soft.

The youngest son, Yios, scurries from a room closest to the maw, rubbing his silt-coated head in a daze, the poor fool, outwitted by the youngest daughter. What he says Yaya already knows: he was about to join his first Forest gathering, the ritual of sharpening a Yios to Baba, when Kori said she’d show him a way to be stronger than all the men. Then something obsidian-hard knocked him on his shingly skull.

Yaya grinds her teeth like flint grating greenstone spice. This girl is more cunning than she ever was. Her own attempt was stopped short, not far from the Cave, because she lacked the stones to incapacitate a Yios and supplant him in his own initiation ritual.

She brushes past the boy, determined to snuff this flame. Determined not to let her own sins repeat, not let anyone else die by foolish attempts to disobey the order of the Cave. This Kori’s existence won’t be sullied by regret.

The Yios protests, but she shuts it in four determined words with sharpness honed by age.

“Stay here. Keep watch.”

For the first time in five hundred risings of the red sun, Yaya will walk the Forest.

###

It’s not the darkness of the Forest that fills Yaya with dread. Not the way the twigs snap and scratch her soles, nor the rough tree bark dressed in fluttering moonlight. It’s the memory of crimson clouds engulfing the trunks and her first Baba, when she was the one who disobeyed the rules.

Now, her bones are hardening, and soon, the stone will wipe away all guilt. But it’s not herself she fears for. It’s the Kori, who staked an entire lifetime to be haunted by regret. Or discarded altogether before the Prowler’s fangs.

The forbidden scent of the Forest is not the pine and honey she remembers. Maybe, it’s her nose that changed, because now all she smells is ash and burning timber. These are heartwarming scents of family, of a bonfire beneath the Cave’s skylight, of Forest stories sons shared by the warmth.

There’s a sound of shifting earth, like when the maw closes in the cave but she knows it’s not that. It’s not a rolling rumble drawing in, it’s one drawing out, not pushing rock to shut a gate, but pulling to open. She is uncertain, this sound unfamiliar but also reminiscent of something evil. Something big gaping its mouth.

Yaya hurries her step, her stone-hardened bones gritting her kneecaps. Alone and old in a strange place, with only her intuition to find the sons. She whistles low and sharp, her puckered lips unfamiliar with using this sound for anything but a song. To whistle with Cave-daughter lips is to sing, but in the Forest it is to warn of danger, or being lost. It’s the whistle of Cave Sons.

A whistle back. And soon there’s footsteps, faint beneath the rumble, she feels the vibrations through her heavy bones, like she’s one with the earth already.

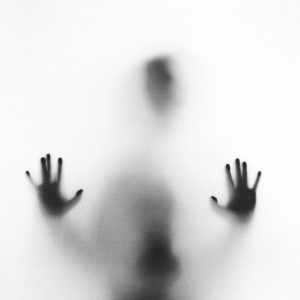

She takes another step. A trail of voices slithers beyond her reach of sight, but also something from behind her: a low growl. The presence of a thing that raises the hair on her hunched back. The absolute certainty that to turn around is immediate death. Memory of that presence worms inside her mind, when first Baba raised her from the ground and warded her eyes before the Prowler’s gaze.

Warmth reaches her cheeks, carried by putrid breath, and she imagines all the things rotting within the belly of the beast.

An image swells her mind, of her hardened bones gathering mold in Forest mud away from family rock, her crusted face eternally calcified inside the Prowler.

Despair grips her heart, and now she truly feels that Kori and Mama are names too distant from her; she is Yaya body and soul. Old and slow, straying where she should not, to die far from home and never become the bedrock. The Cave betrayed, its promise broken—Yaya will be deprived a place beside her precursors.

And Kori will never forgive herself. She’ll be as Yaya, a ghost demanding others stay in line because she blamed her own self for once failing to do so.

Warmer, the breath touches her earlobes, assaults her tongue with bitter taste of char.

Be still as stone. It’s all she can do. Rock has seized her already, and maybe the Prowler will think her a boulder, a thing too tough to devour.

She shivers. Not for fear of her life, but for her kin. Has the Prowler devoured the soft Kori whose flesh is too tender for the Fog?

But there’s something odd. No twigs snap beneath the weight of the beast. Instead, they crackle, gently like rodent bones cast in the flame. Over her shoulder, an appendage grazes her skin. It does not pierce as she expects a fang to do, it gently touches: a hand hot as molten ore, ethereal and crimson like she remembers the Fog to be.

Unable to resist the pull of curiosity, she twists to witness her first Baba, the one who saved her life, a ghost whose body is cloaked in misty red. He stinks, just like when she lost him, of burning flesh and seared hair.

Her shoulder aches where he touched it, seared but too elder-thick to burn. Kori was right. Rock does not recede before the flame so easily.

“Baba?” Her voice quakes. The name nostalgic on her tongue, because although she has been surrounded by Babas, she never called them that. To her they are all Yios, sons too young to compare with her vastness of experience. But not this one. This one is older, ancient.

“You should not be here.”

Just like then. His words carry the same cadence, the same roughness of judgment from across five hundred risings of the sun. The words untether her from time, shear her wisdom, strip her down to a vulnerable Kori once again.

But she has the hardened heart of age inside her, a stone that may grind but will not shatter. She knows to speak her truth despite the grating of emotion. “I know. But this time, I don’t come seeking adventure. It’s another I’m here for. A Kori that joined the ritual hunt, supplanting Yios in his own initiation. Fool like me.”

Footsteps shuffle in the distance, whistles and voices scrutinize the Forest for her. But she dares not whistle back—dares not attract them closer. Whatever her first Baba was, she cannot be sure what he is now.

“It is for Babas to save her then,” Baba says. “The Fog is coming. They won’t be able to save their stone-heavy Yaya too.”

“It was for Babas to stop this from happening in the first place.”

The words feel like a sword piercing out her mouth, to stab at something she never dared to before. To imply it was never her fault—not just her fault.

Baba’s eyes narrow, folds of mist around their eyes glowing as red as the sun. “You changed.”

“I had to. It’s the price of time.”

“Now, you blame me for your sin?”

“Service to the Cave is no excuse for absence,” Yaya says, finding words she never before realized had piled in layers around her heart. She’d felt their meaning for so long but never put them to speech, never even framed them to coherent thoughts. “I wanted to be like you. You dismissed it; you were not there, and that only made it fester. What happened has haunted me with regret.”

“You don’t know regret,” he says.

She does not know? This burden has defined her existence. But the urge to protest is quickly quenched because realization dawns on her, witnessing him be a part of the Fog and the Fog a part of him. All the pieces of her vast experience gather to one conclusion: “The Prowler,” Yaya says. “He’s not real. Is he?”

Baba remains expressionless, or maybe the shifting of his features is masked by a misty facade. “No.”

“Why do the sons make up this story?”

But she knows the answer. An illusion is precious to sustain, lest its shattering makes the world an even darker place. “Stories,” Baba says. “Protect our minds. Some knowings have no benefit.”

There is no beast, there never was—no living one at least. Not living in the same way they are. It’s easy to assume what the Fog wants. It’s the same thing as the Cave. To grow, to encompass. “You will kill me? Deprive the bedrock of its arduously aged fruit, pilfering it for the Fog?”

Mist shudders around him, and she understands what Baba means about regret. He has become part of this vaporous force, a servant with a shackled mind. How many sons of the Cave has he consumed to feed the Fog? “I cannot control what I’ve become. It’s the sight of your face after so long that made memory yank my soul from the depths. Not for long.”

Darkness sinks inside her, but her breathing does not quicken, her body does not tremble. Kori’s unyielding will infect her, a cobble daring to roll through a crushing world. Yaya’s heart was once a grit, fragile and wavering to creation’s capricious winds. But since then, it has gathered ore that has hardened and transformed into a precious metal of its own. There is no beast to conquer, no outside world waiting for them. They are pawns of a war between two unconscious forces. They are here to be devoured.

That is the way of the world. And it changes nothing. “I will protect my family.”

For the first time, his expression changes, enough to form a crack in this eldest daughter’s heart. He smiles. “I expect no less from you, dear Kori.”

The echo of that word rings differently when aimed at her. The same name means a thousand things to her, but from Baba’s lips, it is enough to make her clay-filled eyes leak runny salt.

A rumble. An opening of a mouth that she can now witness: it’s the earth itself, fissuring to unleash another puff of Fog. It’s not a formless mist but a congregation of son-shaped ghosts. Unlike her Baba, their eyes have dulled of conscious spark. Like the faces in the Cave, these ones have lost themselves and exist in-between as appendages.

Another sound—this from behind her: a yell of a foolish daughter who has not been taught to keep quiet before the Fog. “Yaya!”

Yaya turns. She sees her reflection in this Kori, from across time. Desperation, guilt, a rushing of thoughts of how things could have been done differently. Yaya sees it all passing across Kori’s gaze. It can’t be helped; the chain of regret will be passed on. But she will let no screams cloud the memories of this one.

Living Cave-sons swarm around her, crouch determined with harmless stone-carved spears pointed at the Fog and baffled, glimpses at Yaya.

“You will run,” Yaya says to Kori. It’s not a request, not even an order. It’s a fact that bears no protest.

Warmth rises on her back as Yaya hunches lower, thrusting her arms into the muddy earth with far more ease than the hardened innards of the Cave. Wet around her forearms, warmer the deeper her fingertips reach.

Behind her a familiar scream rises, Baba trying to resist the Fog’s command. He is as always a strong-willed son. But Nature’s forces always win.

Ahead another familiar scream: one that reflects her own protests years ago when she screamed Baba. Only this Kori screams Yaya instead as men taller and stronger than her drag her kicking. Wise to know the Fog cannot be harmed by son-made toys.

On runny dirt beneath her, beside the skin of her forearm a face forms: crushed twigs are the bridge of a snout, the eyes are pockets in the mud. And it occurs to her that the Forest too seizes full-grown life to grow itself. She wonders what Forest people had lived and died to grow the mud, to grow the trees. If they were people or beasts. Or something else entirely.

What does it matter? It all seeps down eventually. Like Fog swallowed by the Forest dirt gaping its maw or stone settling at the bottom of the Cave. “We all become the bedrock of this world.”

Her fingertips reach something hard and with a roar she grasps the rock of the earth and sends a fissure spiraling on either side. She is slow, she is a boulder weathered with age, she is a slab so strong that can rub against the earth to form an earthquake of her own.

As cracks branch out and separate Fog from family, as the dead Cave-sons claw with lava fingers through her flesh, claiming her life, Yaya raises her head, glimpsing Kori, the youngest cobble, staring at the oldest boulder, scratching the iron grips of Babas as they recede into the woods, raising a guttural warcry to the skies too powerful for one her age.

It burns but Yaya does not allow the hurt to show, choosing another expression to depart with. Because Yaya knows regret is better carried, if the memory is softened with a smile.