I.

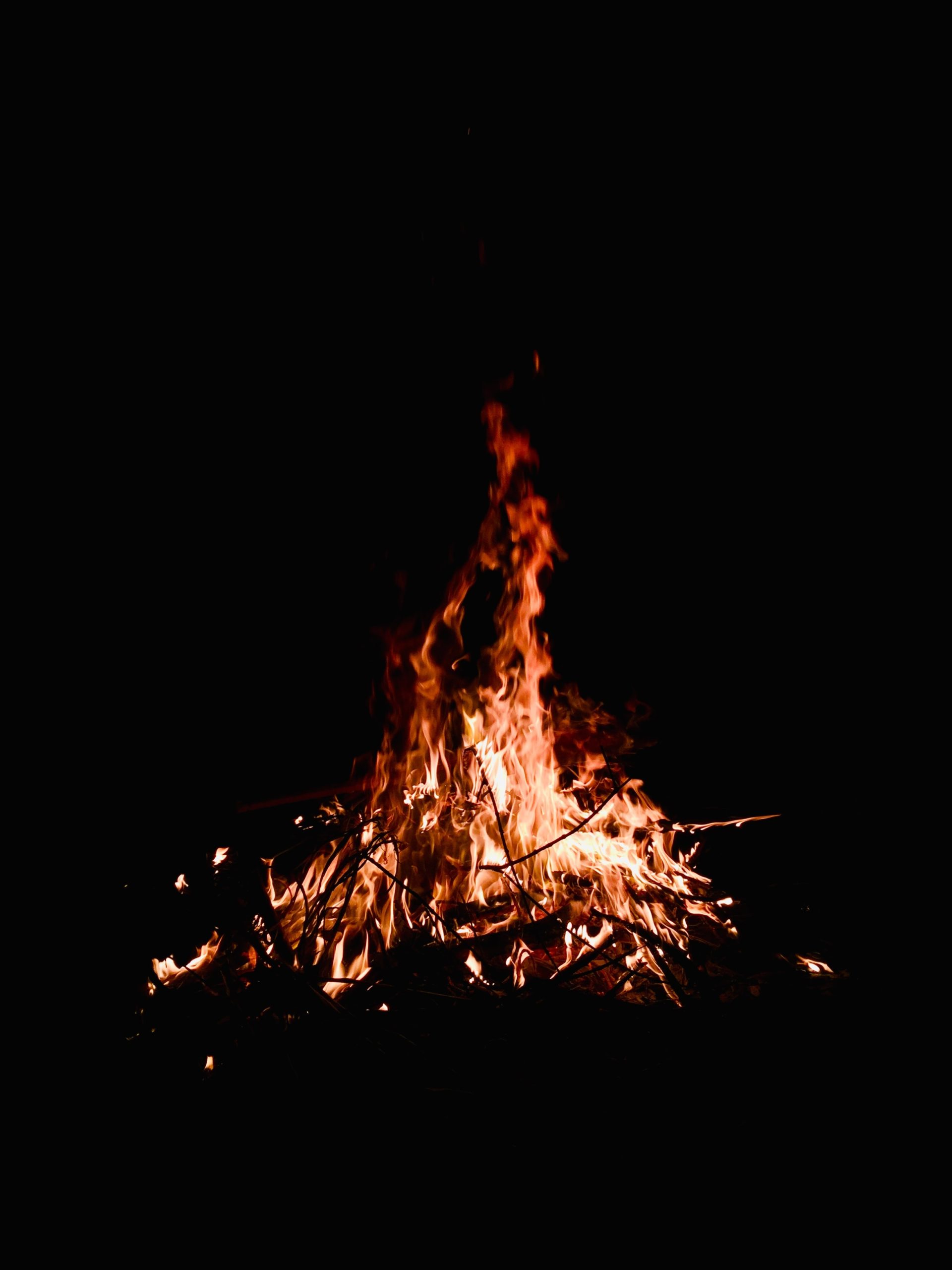

The chief priests chanted hymns over the bonfire’s raging flames that first night in Izuland. Their voices were unnaturally high-pitched, a shrill tone I feared would tear the cords of their voice boxes out of their throats. They threw herbs into the fire, discoloring the flames into a cold green conflagration that screeched in the whispers of forest spirits and stank of rotting soil.

I noticed him because he sat by the fire all through that evening. Alone. Very few dared approach the bonfire that night, even long after the wizened chief priests had completed their rituals for the festival and left. There was a quiet eeriness about the fire as if the spirits the chief priests had invoked for protection still lingered close by.

It must have been intentional, I thought. He must have wanted me to notice him because he did not seem too keen on hiding the glances he cast toward my direction every few minutes. The other youths looked too, and I knew they did. Anybody would after beholding the procession of the Betrothed earlier that afternoon. I liked to think I’d resembled a water spirit myself, wrapped in flowing white satins along with the other chosen maidens as we signaled the start of the festival of the New Season.

And yet there was something about the way the waning flames of the bonfire painted his face. The fires splashed an incandescent sheen over his dark skin, and his eyes twinkled behind the flames like fireflies were trapped within his irises. When I caught him staring, he didn’t turn away like the rest of the young men did—too bashful to be caught beholding a treasure beyond their comprehension. Instead, he smiled confidently, right at me, and my treacherous heart skipped a beat.

Early on the second day of the festival, before the morning fog lifted, the Four Villages camped out under the palm frond canopies of the palm trees that Izuland was known so much by. The event was an exhibition of song and lore. The thicker the fog, the greater the number of attending spirits to witness our craft. A serenade in exchange for another year of blessings.

Of course, the children were kept indoors. The fog could be greedy sometimes.

The storytellers of the Four Villages wove words into image and melody. When he came up, representing no village, his voice rang out in the sonorous timbre of a poet. The forest sang along with his verse, a haunting tune of love and loss. The fog leaned closer to his voice—if that was even possible—and I could have sworn I felt the wetness of the spirits settle over my skin. Somehow his eyes managed to meet mine, albeit veiled, in the midst of three of the other Betrothed.

I thanked Izu for my dark skin and the way it hides the crimson flush of my cheeks.

On the third day, the festival of the New Season peaked. The evening air was thick with the aroma of roasting lamb and fragrant herbs. The bonfire blazed as the Four Villages danced to the fervent rhythm of the ogene and the spirit flute. The air was chilly, but even the harmattan cold was lost to the twisting of bodies around the fire. Some of the Betrothed had even joined in the dance.

He found me at the edge of the palm trees. Not too far from the fire, but far enough for everyone to forget about me for a minute.

“Hello,” he said simply. “Do you think they’ll mind?”

A million thoughts crossed my head at once. About how he was speaking to me when no man in their right mind would. About how his voice sounded just like it did when he sang his poem the other day, and it was not just a performance. About who the hell he was referring to, and why did he have to ask their permission?

Yet no words were formed.

“I heard the gods in this land are a jealous kind,” he continued. “Izu. Do you think they’ll mind?”

Oh…

“Yes,” I said at last, mustering all the primness and regal composure that all the men of the Four Villages fantasized about the Betrothed. “I think they would.”

“I’ll take my chances,” he replied. “I would immolate myself if I traveled four villages and didn’t speak to the most beautiful maiden I’ve ever seen.”

“I’m not the most beautiful,” I said, deflecting the flattery. Flattery that could end family lines if Izu so wished. This man was clearly an outsider.

“Our Eze-nwanyi is. You should have seen her lead the procession.”

“I’d say the beholder’s eyes tell a different story.” It was funny, so I laughed. Also, I was hoping it would calm the fervor that had kicked up in my own heart.

“I’m Nosa,” he said, offering his hand. “What’s your name?”

I glanced at his outstretched palm and hesitated.

“…or will Izu smite me for exchanging a few words with their future wife?”

“Very likely.”

“That sounds like a very insecure deity. Don’t they have enough wives already?”

He was so bold it was terrifying. Yet, there was an excitement it stirred within me. A quiet rebellion of sorts. As gently as I could, I took Nosa’s hand in mine.

“Olaedo.”

*

By the seventh night of the festival, I could not imagine a life without Nosa.

The festivities of that third night had run well into the night, especially when the freshly tapped palm wine changed serving hands and the fermented drinks began to kick in. It was enough of an excuse for the rest of the Betrothed to forget about me, and for me to listen to Nosa talk all night. He wasn’t from Izuland. In fact, he wasn’t from any of the Four Villages. He claimed he was from somewhere much farther north, where the sun was as harsh as the landscape. I didn’t doubt him. After all, there was a harshness to his dark complexion that I’d never seen before in the Four Villages… even though I myself had never left Izuland.

He asked me how I became Betrothed to Izu, and I told him. Once in four years, when the second month was longer by an extra day, a girl child was born. On that extra day. That child would then be taken to the Eze-nwanyi and raised among the other Betrothed to become Izu’s wife.

“And this happens every four years?” Nosa asked. “There’s always a birth?”

“There isn’t anybody alive who has ever experienced it not happen.”

On the fourth day, the Betrothed had another procession. This time it was a formality, preceding the village pageantry. At twenty-two years, and with two years left to my Wedding, I stood a head taller than all of the others. The crowd cheered mindlessly, but I could not help but search the excited faces for Nosa. Would he be cheering too?

To my surprise, I was slightly disappointed when I did not spot him.

There was a wrestling match the next day. The winners would stand eligible to ask the hand of the maidens who won the pageantry a day earlier. The excitement was palpable as youths grappled themselves over the red sand of the village square. Muscles glistening with sweat rippled under the sunlight. The square was thick with cheering and a slightly suffocating virile exuberance. Quietly, I excused myself from our stands and strode towards the copse of palm trees. Nosa was there, seated underneath the cool shade on a mat. I was surprised to see him, then admonished myself almost immediately. Would I have come in this direction if I didn’t at least expect him to be there?

I walked as slowly as possible, emotions wound around my chest in a tight cord. He smiled when he saw me approach and patted the spot beside him on the mat. I obliged.

“I didn’t see you at the pageant yesterday.”

“There was no need. I must confess that meeting you has reset my mental bar for beauty. You’ve ruined me Olaedo.”

I felt lightheaded, but, “Mere words, Nosa. Of what difference does it make, calling an already blue sky, blue?”

“I didn’t think I needed to take off my shirt and fight in the sand to get your attention.”

“You think pretty highly of yourself, poet.”

“I want to marry you, Olaedo.”

My response stuck in my throat. “I-impossible.”

“I’ve been at the shrines. Reading the texts. It’s not impossible. Just… very difficult.”

I didn’t like where this conversation was headed. “Stop all this foolish talk Nosa.”

“It’s not foolish talk,” he replied, maintaining a calm demeanor. “Think about it Olaedo. We could travel. The world is larger than the Four Villages. There is so much out there, so many strange creatures. Spirits. There are even lands where gods walk among mortals!”

I scoffed. “Why would gods want to walk amongst us?”

“The same reason some sages cast away their human flesh for an undying iron body.”

“Abomination!”

Nosa chuckled. “Things are done because they can be. Marrying you is possible. Or perhaps I was wrong and you don’t want to see the world with me?”

I wanted to protest, but he had such a way with words that it was hard to object. Each sentence drew me in, just like the spirits he had serenaded with his poems. Nosa spoke of the desert hamlets and I could almost taste the dust in the air and the heat on my skin. Even though we were nested completely in the shade. Before I knew it, I was leaning too close, taking in the smell of his shirt and the warmth of his skin. Hot blood pumped against my ears, my chest, my fingers, everywhere.

That evening, Eze-nwanyi gave me a stern lecture about Izu and their righteous jealousy. About the ruthlessness of their punishment if I dared be unfaithful. I was the next in line to be Wedded, I should not be foolish.

The next night Nosa held my hands by the stream and swore we would live together forever. That he had consulted the chief priest of Izuland, and the only way Izu would let me go was if only Nosa would run a gauntlet that the god had decreed.

On the seventh night, Nosa was gone.

*

II.

For the first few weeks after the festival of the New Season, all I could think about was Nosa. The older Betrothed would look at me with a knowing pity that I did not understand until Eze-nwanyi called me aside and told me the story of a Betrothed she had known when she was much younger. Her name was Ezinne, and she had fallen in love with another mortal. However, Izu was not the kind of god to let go of their belongings so easily. Instead, they mandated Ezinne’s lover to complete seven tasks.

Ezinne’s lover never came back.

And Ezinne, broken by the god’s injustice, took her own life before her Wedding. Maybe it was in sorrow. Maybe it was to spite Izu. Either way, Izu’s wrath fell on the village as pestilence and death until the next fourth year. Eze-nwanyi looked me in the eyes; an all-knowing sagacity deepened the crow’s feet by her eyes.

“Forget about him, Olaedo.”

I refused to listen, but weeks bled into months which bled into a year, all with no word from Nosa. Was it all a fantasy then, believing Nosa’s stories and dreaming of a world outside Izuland and the Four Villages? I recalled Ezi-nwanyi’s words of warning on the last festival. I’d been foolish indeed.

And so, with a heavy heart, I prepared for the procession that signaled the commencement of the festival of yet another New Season.

*

The air was particularly chilly that morning. We stood in a line like we always did, with Eze-nwanyi leading the procession. A thin silk veil covered my face, and I held a small bouquet of flowers to my chest. The petals were an immaculate white that stood out in sharp contrast to the golden fabric of my gown. Cheering was not allowed during the procession, for this was only a symbolic display of the blessings of the guardian deities.

I walked through the motions, mindlessly repeating hours of practice in the Betrothed settlement. Nosa had been an aberration in my life. A singularity that had turned my entire world upside down. If he had never shown up, I would have been content with the lustful stares of the men in the crowd. In his arms, I had tasted a freedom that I’d never known existed. A commotion had begun somewhere in the crowd, but I paid it no heed. I would run my routine, and the chief priests would burn the fire and taint the flames with their concoctions tonight. The only difference would be that he wasn’t there.

A hand grabbed me by the small of my back and pulled me away from the procession. My heart nearly stopped as Nosa pulled me into an embrace. I could not breathe. I could not think. The faces in the crowd had frozen in terror like Izu would descend from the heavenly mists and smite us all.

“I completed the god’s challenge!” he declared, grinning from ear to ear. “We are getting married!”

I fainted.

*

When I asked Nosa when we would leave Izuland, he simply replied to me, “We aren’t leaving.”

It was a punch to the gut. “Why not?”

“It was one of their conditions.”

“And you agreed?”

Nosa held me by my shoulders. “There’s no point in wandering after finding what I’ve been searching for.”

His eyes were still as intense as ever, but I noticed the new scars on his body. Ones that were not there before. Nosa was a traveler, and he’d always had the physique to show for it. A year later, he looked completely different. Tired even.

“And you won’t tell me what they asked you to do?”

He smiled, and I knew the answer before he told me it was another one of their conditions.

*

III.

Nwaoma was born on the second month of the next year, which also happened to be the fourth in a four-year cycle, which should have been the year I Wedded Izu as another Betrothed joined the ranks of god’s wives.

That year, none of these happened.

The foreboding was palpable. It had descended upon the village in ghostly silence. I watched Nwaoma cry and feared for my baby. She was not born on the extra day, so I had nothing to worry about. In the presence of four chief priests, I had performed my rites at Izu’s shrine on the final day of the last festival and left the Betrothed settlements with my head held high.

I was free from the god’s marriage, on the condition I never left Izuland.

Nosa and I opted for life at the edge of the village instead, away from the older women who called me names behind my back, and the grumpy men who disliked Nosa for the sole reason that he got to taste forbidden fruit they would forever hunger for.

A month after Nwaoma came, the yam seedlings died in their shoots.

Then a plague hit the cattle, and the chief priest was called in.

Eze-nwanyi came to my house that evening. For a woman at seventy-two, her back was as straight as a tree trunk, and she wore her age like uli that shamed even innocent maidens. She sat with me in the yard as I breastfed Nwaoma, overlooking a copse of pawpaw trees that Nosa had recently taken to cultivating.

“All fingers are pointed at you, Olaedo.” Eze-nwanyi was never one to mince words.

“The gods have cleared my name,” I retorted, somewhat belligerent.

“But nobody can see the gods,” she replied, still calm. “All they can see are their crops dying and livestock falling sick. Children coming down with disease in their lungs. Mothers miscarrying. Who can they blame but the stranger at the edge of town who conspired with an adulterous wife to deceive the gods?”

“Heavens!” I choked. “Do people actually believe that?”

“It’s what they’re saying. Especially the older ones. The ones who knew about Ezinne.”

Fear licked down my spine. “Why are you telling me this, Eze-nwanyi?”

“Because they will be coming for you, my dear,” she rose and placed her index finger between Nwaoma’s tiny fingers. “The gods might be ruthless, but never forget, we humans are the most hateful creatures in this land.”

*

When the rains did not come on the third month after they were meant to, a mob attacked our house. The projectile block of stone tore a hole through the door and crashed inches away from Nwaoma’s crib.

My blood froze in my veins.

Nosa stormed out of the house, a cutlass in one hand. I dared peek through the curtains. There were farmers with rakes and machetes in their hands. They saw Nosa and took wary steps back, even though they had him outnumbered. He raised his cutlass and pointed the blade at the leader. It was the chief priest.

“What is your problem with my house?” he growled, and I’d never seen my husband radiate such deathly rage.

“Take that your wife and cursed child and leave this town,” the holy man hissed. “You people have brought Izu’s wrath upon us.”

“And did your god tell you this nonsense? Since when does the blood of a woman and child solve the problems of an entire village?”

His words seemed to incite the mob. When Nosa entered the house, he gave me an icy glare that almost stopped my heart.

“We have to leave this village now. These people have run mad.”

“But you said Izu would not let us leave.”

He took Nwaoma in his arms, a tempest behind his eyes. “Do you trust me, Olaedo?”

“Always.”

“Then follow me.”

He led us toward the pawpaw trees he had been cultivating the past year. In the middle of the trees, he stopped, and handing Nwaoma to me, he reached for the soil and unlocked a door hidden in the dirt.

“Follow me.”

I swallowed the lump that had grown in my throat and stared into the gullet Nosa had opened in the earth. Wooden steps creaked as I descended deeper into darkness. A light flickered into life somewhere below. Nwaoma whined.

“Nosa?”

The steps led to a cavern of sorts, under the earth. Wooden supports held the roof and walls, and smooth stones lined the floor. Nosa stood in the center, expressionless, with a torch flickering in his right hand.

“Do you remember when I told you about the lands outside the Four Villages? About how spirits and gods walked among humans?”

Nwaoma had started crying. I clutched her closer to my bosom as a cold bead of sweat trickled down my forehead. I nodded.

“That was your god’s task. For me to build them a body to descend into the mortal realm.”

“Is… is that even possible?”

“Oh, so much is possible,” he said, suddenly pacing. “The four year cycles are the periods when their realm draws closest to ours. Olaedo, Izu is no longer in the heavens. This land is no longer under any divine protection.”

“B-but the people. The chief priest—”

“Does not hear the voice of any god. He’s looking for a scapegoat. He wants our blood or the villagers will have his head!”

“Then why aren’t we leaving Izuland right at this moment?” I yelled. “Why are we here, underground, and not running from the hungry mob?”

“Because Izu tricked me,” he said, voice hollow. “Each of the Betrothed is cursed, never to leave Izuland. To leave is to die.”

My chest tightened. “And you never thought to tell me about this? Instead, you lied to me?”

“I’m sorry Olaedo,” his voice was so small. This was not the man I had seen behind the fires.

“I thought we would have more time.” Nosa’s voice hardened again. “We don’t.”

The light of his torch fell on something in the back of the room. Something I hadn’t noticed earlier. It was a casket, but upright, and transparent. Fluid bubbled within, green like the river during flood season.

Within it was… somebody.

Slender arms and legs curled up within the liquid. The eyes were closed, as though asleep. I drew closer to the glass, almost transfixed. I saw my face reflect on the surface of the container, then within it as the light fell on the face of its occupant.

“By Izu…” I choked. “Nosa… W-what is this?”

“It’s made of living steel. The artificers in the southern mountains are masters of this magic. This vessel can hold any soul. Even the divine.”

“After I die.”

“I knew Izu could not be trusted, Olaedo. I’m going to free your soul. With this, we can leave this village, travel the world, raise our child to be free!”

“And I would not be human!” I yelled. Nwaoma was bawling now. “You’re crazy Nosa. Eze-nwanyi was right! Everything with you has just been one foolish rebellious phase since the beginning.”

“Olaedo, wait!”

But I’d reached the steps and started climbing, all the while trying to calm my troubled baby. I was almost at the edge of the trees when I noticed that something was very wrong.

The mob had returned and the house was ablaze. Thick smoke polluted the air and Nwaoma cried harder. Somebody heard the cries amidst the din and yelled to the others.

“The witch is in the trees. Get her!”

Desperation clawed at my insides, and I turned tail and ran. The thunder of the pursuers’ feet rumbled behind me. I clutched Nwaoma to my chest, muscles burning as I ran. I ran. I ran.

Something cold ran through my calves, and I screamed. Pain streaked like flashes of lightning through my body but I could not stop. My baby. Nwaoma!

Somebody crashed into me. The mob had caught up. “Please!” I begged as Nwaoma screamed into the night.

Nobody was listening.

*

My eyes fluttered open. I found myself lying at the back of a cart. The air felt strange on my skin, and it took a while before I noticed it didn’t fill my lungs. A column of smoke rose into the sky a good distance off, and even the sight of the black smoke against the night sky felt different… like the colors were something new.

“Are you awake?” I almost jumped at the voice. It was Nosa at the front of the cart.

“You must be confused. Must have questions. I’m sorry. I shouldn’t have let you leave the shelter. I didn’t find the both of you until much later.”

My head was spinning. “Nwaoma.” A creeping desperation found its way to my voice. If this was even my voice. “Where is Nwaoma?”

There was a long silence. “There was no vessel for her,” he sniffed. “I couldn’t… she died.”

I screamed.

“You should have let me die with her!” I tried to lash at him, but my body did not move. I was bound with thick ropes to the back of the cart. My rage swelled some more. “You bastard! You had no right!”

“I’m sorry,” he whispered, somewhat broken. “I couldn’t lose both of you. I couldn’t bear it.”

I didn’t care for his sorrow. “Untie me right now!”

“Please, Olaedo.” Nosa’s voice was barely a whisper. “I know you’re in pain, but one strike from you is potentially lethal to me. I can’t let you harm yourself, either. I’m sorry. I truly am.”

I turned my back from him, as far as my restraints allowed. In that moment, I did not pity him. I did not try to understand his loss or his pain. Only how to make him feel as much pain as I was feeling. Even more. How selfish had he been to make me relive this, all because he could not live with it alone?

“It’s all your fault,” I hissed, even though it was the entire Izuland that had turned against our family. “I never wanted to marry you in the first place. I will never forgive you Nosa.”

He said nothing. Under the night sky and the rumble of hooves, a silence descended between us, splitting wide like a chasm. Eze-nwanyi had called humans the most hateful creatures in the land. In the end, I was no different.

I wept, but this body made of living steel had no tears to shed.